Border Crisis Is Personal in Battleground US House District

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

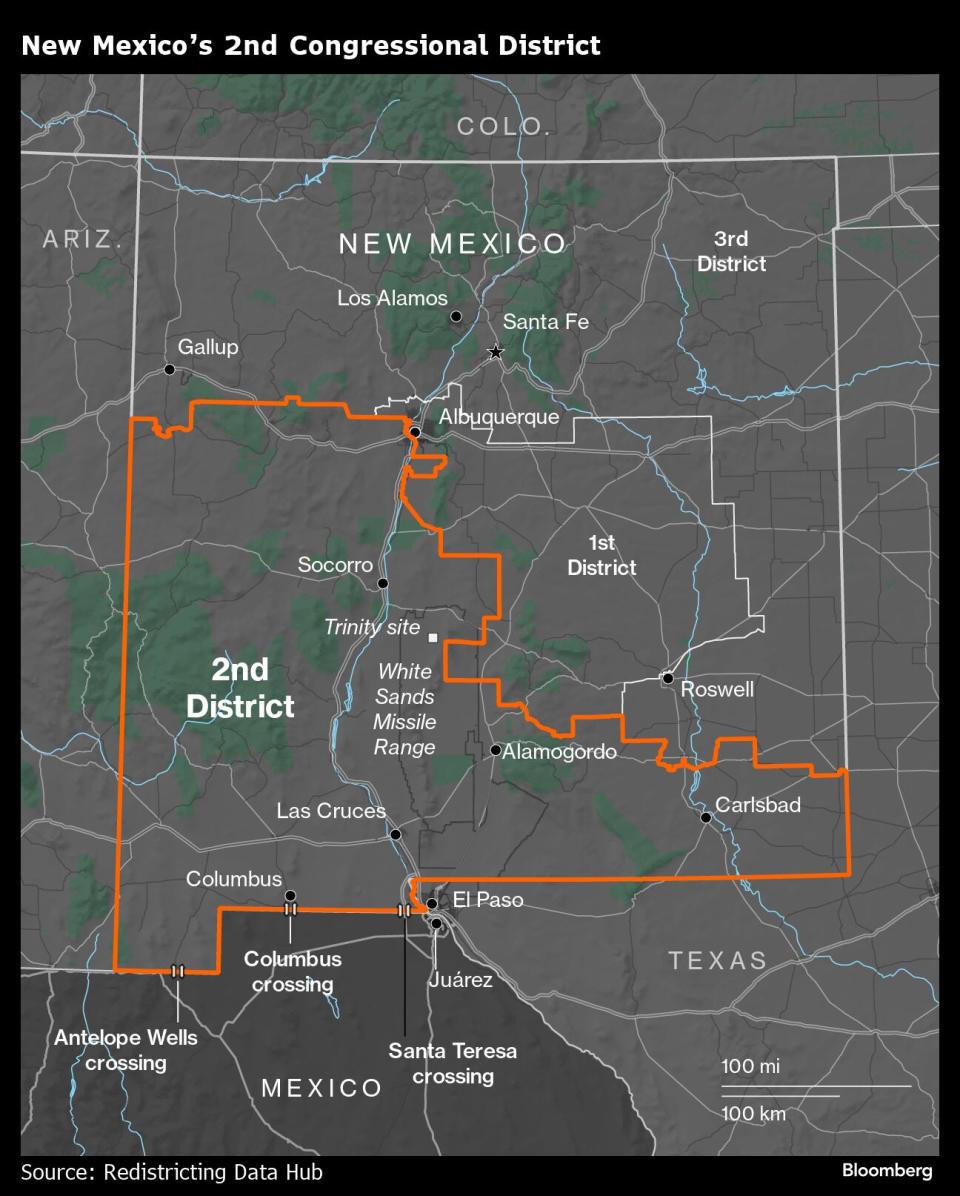

(Bloomberg) -- New Mexico’s southernmost congressional district is home to haunts of Billy the Kid, the site of the first atomic bomb detonation and the most political turnovers in recent US House history.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Dubai Grinds to Standstill as Cloud Seeding Worsens Flooding

What If Fed Rate Hikes Are Actually Sparking US Economic Boom?

China Tells Iran Cooperation Will Last After Attack on Israel

Powell Signals Rate-Cut Delay After Run of Inflation Surprises

US Yields Spike as Hawkish Powell Puts 5% in Play: Markets Wrap

This quirky and unpredictable area, which earned the nickname the “swingiest” of swing districts by changing hands each election cycle since 2018, will help determine which party wins control of the US House in November.

Democrat Gabe Vasquez, 39, won the House seat in 2022 by less than 1 percentage point — about 1,350 votes — over then-GOP incumbent Yvette Herrell, 60. The two are now headed for a rematch and Republicans see a win here as key to growing their tiny House majority.

Adding to the drama of this tight race is its geography: it shares a 180-mile border with Mexico, placing it at the epicenter of one of the most contentious issues of the 2024 election.

“Tell Gabe Vasquez to end his dangerous open-border policies. American lives are at stake,” declares a National Republican Congressional Committee digital ad running in the district.

But voters here, while historically more conservative than in other areas of the Democratic state, don’t tend to embrace Donald Trump’s aggressive immigration policies.

Fifty-five percent of the voting-age population is Hispanic, and among the most acute issues are the humane treatment of migrants and the identification and return of bodies found in the desert.

There’s also no financial incentive here to shutting the border. Development near the border checkpoints drives the economy in many of the dusty towns near the state’s three crossings.

“Political campaigns based on fear of the border — depictions of criminals running through our fields, looting and raping — don’t work here,” said Jerry Pacheco, 58, president of the Border Industrial Association, a local economic group based in Santa Teresa.

Economic Realities

This border district has a different vantage point than New York and other northern cities straining under the financial costs and societal burden of the migrant surge.

It’s also unique among its neighbors on the border. Officials here in a safe Democratic state aren’t moving to militarize the border like in neighboring Texas, a Republican stronghold, or even Arizona, a swing state.

“There’s a lot of empathy and acceptance, and so many people here with family on the other side of the border, real familial bonds,” Pacheco said

Republican Philip Skinner, 76, the schoolbus-driving mayor of the tiny border village Columbus, confided recently that he’s “not a Trump Republican” and would cool to Herrell if she got too close to the former president.

What motivates Skinner is growth at Columbus’ port of entry, — one of the state’s three, along with Santa Teresa and Antelope Wells.

Within New Mexico’s border counties the economy has generally been growing at a slower rate than the rest of the state, according to the state’s Legislative Finance Committee.

But border communities have made strides in retail trade, health care, and transportation and warehousing, and boosters like Skinner and Pacheco wants to seize on that momentum.

“I don’t care if you’re Republican, independent or Democrat. If you can help us, we’re for you,” Skinner said.

Shared History

Cross-border ties are embraced in Columbus, both as an economic and a cultural necessity.

Residents commemorate Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa’s surprise 1916 attack with a fiesta and a binational horseback “friendship ride.”

The annual bash, a seemingly incongruous celebration of a deadly battle that prompted a US counterattack, exemplifies the complexity of border politics in the region.

New Mexico has the highest percentage of Hispanics of any US state and many of its laws — such as obtaining a driver’s license — are friendlier to undocumented immigrants than its neighbors. New Mexico doesn’t require proof of citizenship or legal residency to obtain professional or occupational licenses, and it provides eligible undocumented students with access to in-state tuition and financial aid to public colleges and universities.

New Mexico is also the only border state that allows overweight cargo from Mexico to enter and unload in a six-mile radius, the state’s Legislative Finance Committee also has found. And wait times for crossing in New Mexico are about a quarter of what they are in nearby El Paso, Texas.

Democratic Freshman

Vasquez, a former city councilor in Las Cruces, the state’s second-largest city, epitomizes these cross-border connections.

At campaign events, Vasquez moves adeptly between English and Spanish and frequently discusses his upbringing, which spanned both sides of the Mexican border.

Vasquez pro-actively speaks about border security and immigration issues, pushing for more federal investments on technology and border personnel. He also wants better conditions for migrant detainees, and tougher criminal sentences for human-trafficking crimes against minors.

“We have to represent everybody across this big district,” he said at an event a few miles from the Santa Teresa border crossing. “We have to listen to everybody.”

For many Vasquez supporters in the district, that also means focusing more resources on humanitarian responses to the cross-border traffic.

“We’ve seen a lot of bodies discovered in the desert,” said community activist Ytzel Cano, 24. Vasquez has been receptive to those concerns, she added.

Republican Comeback

Herrell, an enrolled member of the Cherokee Nation and a former state legislator, needs to walk a careful line if she’s going to make a comeback.

At a diner in Alamogordo, about 15 miles from White Sands National Park, Herrell surmises that Trump’s position at the top of the Republican ticket could help with GOP turnout in the election, giving her the extra votes she needs to best Vasquez.

But her feelings about the likely GOP presidential nominee are complicated. Trump lost in New Mexico in 2020 by almost 100,000 votes, a nearly 11 percentage point difference.

Herrell said she’d like Trump to stump for her this year, but stresses her race isn’t a referendum on the former president.

“Whether I’m tied to Trump, or not tied to Trump, I think it’s more about who I am,” she said.

On the border, she advocates GOP-favored policies such as finishing the border wall, reinstating the “Remain in Mexico” policy, ending “Catch and Release,” and immediate detention of any unauthorized migrants charged with crimes.

That strikes a cord with Otero County Sheriff David Black, who nodded in agreement at a recent event.

Black says he’s worried about migrant “gotaways” who evade patrols, and how immigration is the vehicle for cartels importing violent crime and drugs into the country.

Redrawn District

Those stances are popular in safely Republican districts, but could prove tricky here.

State Democrats redrew the district before the 2022 election to make it more advantageous for the party.

The conservative-leaning Permian Basin oil-producing region was sliced up and its power diluted. And other conservative rural areas were exchanged for heavily Hispanic and Democratic parts of Albuquerque.

Still, Vasquez just barely won in 2022, and the 2024 match is considered a toss-up despite Democrats having an 11 percentage point edge over Republicans in registered voters. Twenty-six percent of voters here are registered as others, creating a significant wild card population.

Columbus Municipal Clerk Omar Carreon, 50, a Democrat, has his own theory about why the district is so swingy.

“Latinos here tend to be more Democratic — but usually, probably more conservative Democrat,” he said. “They might not have an issue voting Republican if it lines up with their way of thinking. They might tend to flip.”

--With assistance from Dave Merrill.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

A Resilient Global Economy Masks Growing Debt and Inequality

Cities Use AI to Help Ambulances and Firetrucks Arrive Faster

The Shadow Swiftie Economy Booms With Bootleg Bracelets and $1,150 Bodysuits

Top Takeaways From Businessweek’s Investigation of Teenage Sextortion

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.