Book excerpt: "Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth"

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Avi Loeb's new book, "Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth" (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), examines evidence of an object of interstellar origin that the Harvard astronomer suggests was manufactured.

Read an excerpt from the book's introduction below – and don't miss David Pogue's interview with Avi Loeb on "CBS Sunday Morning" May 16!

When you get a chance, step outside, admire the universe. This is best done at night, of course. But even when the only celestial object we can make out is the noontime Sun, the universe is always there, awaiting our attention. Just looking up, I find, helps change your perspective.

The view over our heads is most majestic at nighttime, but this is not a quality of the universe; rather, it is a quality of humankind. In the welter of daytime concerns, most of us spend a majority of our hours attentive to what is a few feet or yards in front of us; when we think of what is above us, most often it's because we're concerned about the weather. But at night, our terrestrial worries tend to ebb, and the grandeur of the moon, the stars, the Milky Way, and — for the fortunate among us — the trail of a passing comet or satellite become visible to backyard telescopes and even the naked eye.

What we see when we bother to look up has inspired humanity for as far back as recorded history. Indeed, it has recently been surmised that forty-thousand-year-old cave paintings throughout Europe show that our distant ancestors tracked the stars. From poets to philosophers, theologians to scientists, we have found in the universe provocations for awe, action, and the advancement of civilization. It was the nascent field of astronomy, after all, that was the impetus for the scientific revolution of Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, and Isaac Newton that removed the Earth from the center of the physical universe. These scientists were not the first to advocate for a more self-deprecating view of our world, but unlike the philosophers and theologians who preceded them, they relied on a method of evidence-backed hypotheses that ever since has been the touchstone of human civilization's advancement.

•••

I have spent most of my professional career being rigorously curious about the universe. Directly or indirectly, everything beyond the Earth's atmosphere falls within the scope of my day job. At the time of this writing, I serve as chair of Harvard University's Department of Astronomy, founding director of Harvard's Black Hole Initiative, director of the Institute for Theory and Computation within the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, chair of the Breakthrough Starshot Initiative, chair of the Board on Physics and Astronomy of the National Academies, a member of the advisory board for the digital platform Einstein: Visualize the Impossible from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and a member of the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology in Washington, DC. It is my good fortune to work alongside many exceptionally talented scholars and students as we consider some of the universe's most profound questions.

This book confronts one of these profound questions, arguably the most consequential: Are we alone? Over time, this question has been framed in different ways. Is life here on Earth the only life in the universe? Are humans the only sentient intelligence in the vastness of space and time? A better, more precise framing of the question would be this: Throughout the expanse of space and over the lifetime of the universe, are there now or have there ever been other sentient civilizations that, like ours, explored the stars and left evidence of their efforts?

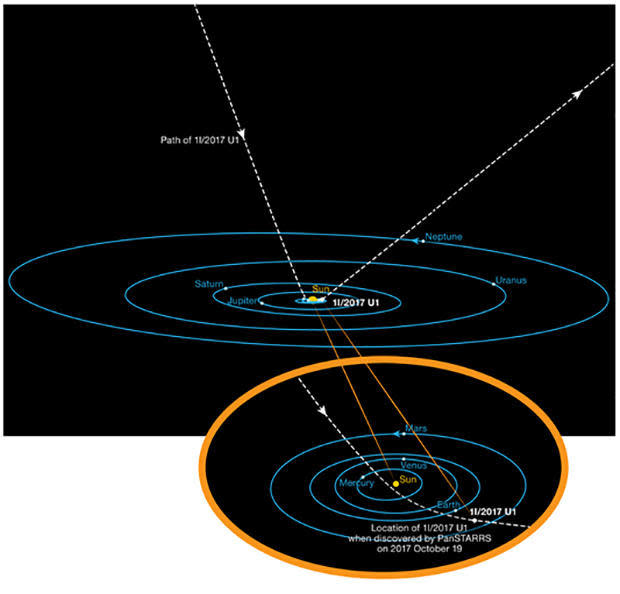

I believe that in 2017, evidence passed through our solar system that supports the hypothesis that the answer to the last question is yes. In this book, I look at that evidence, test that hypothesis, and ask what consequences might follow if scientists gave it the same credence they give to conjectures about supersymmetry, extra dimensions, the nature of dark matter, and the possibility of a multiverse.

But this book also asks another question, in some ways a more difficult one. Are we, both scientists and laypeople, ready? Is human civilization ready to confront what follows our accepting the plausible conclusion, arrived at through evidence-backed hypotheses, that terrestrial life isn't unique and perhaps not even particularly impressive? I fear the answer is no, and that prevailing prejudice is a cause for concern.

•••

As is true for many professions, fashionable trends and conservatism when confronting the unfamiliar are evident throughout the scientific community. Some of that conservatism stems from a laudable instinct. The scientific method encourages reasonable caution. We make a hypothesis, gather evidence, test that hypothesis against the available evidence, and then refine the hypothesis or gather more evidence. But fashions can discourage the consideration of certain hypotheses, and careerism can direct attention and resources toward some subjects and away from others.

Popular culture hasn't helped. Science fiction books and films frequently depict extraterrestrial intelligence in a way that most serious scientists find laughable. Aliens lay waste to Earth's cities, snatch human bodies, or, through torturously oblique means, endeavor to communicate with us. Whether they are malevolent or benevolent, aliens often possess superhuman wisdom and have mastered physics in ways that permit them to manipulate time and space so they can crisscross the universe — sometimes even a multiverse — in a blink. With this technology, they frequent solar systems, planets, and even neighborhood bars that teem with sentient life. Over the years, I have come to believe that the laws of physics cease to apply in only two places: singularities and Hollywood.

Personally, I do not enjoy science fiction when it violates the laws of physics; I like science and I like fiction but only when they are honest, without pretensions. Professionally, I worry that sensationalized depictions of aliens have led to a popular and scientific culture in which it is acceptable to laugh off many serious discussions of alien life even when the evidence clearly indicates that this is a topic worthy of discussion; indeed, one that we ought to be discussing now more than ever.

Are we the only intelligent life in the universe? Science fiction narratives have prepared us to expect that the answer is no and that it will arrive with a bang; scientific narratives tend to avoid the question entirely. The result is that humans are woefully ill prepared for an encounter with an extraterrestrial counterpart. After the credits roll and we leave the movie theater and look up at the night sky, the contrast is jarring. Above us we see mostly empty, seemingly lifeless space. But appearances can be deceiving, and for our own good, we cannot allow ourselves to be deceived any longer. …

•••

Most of the evidence this book wrestles with was collected over eleven days, starting on October 19, 2017. That was the length of time we had to observe the first known interstellar visitor. Analysis of this data in combination with additional observations establishes our inferences about this peculiar object. Eleven days doesn't sound like much, and there isn't a scientist who doesn't wish we had managed to collect more evidence, but the data we have is substantial and from it we can infer many things, all of which I detail in the pages of this book. But one inference is agreed to by everyone who has studied the data: this visitor, when compared to every other object that astronomers have ever studied, was exotic. And the hypotheses offered up to account for all of the object's observed peculiarities are likewise exotic.

I submit that the simplest explanation for these peculiarities is that the object was created by an intelligent civilization not of this Earth.

This is a hypothesis, of course — but it is a thoroughly scientific one. The conclusions we can draw from it, however, are not solely scientific, nor are the actions we might take in light of those conclusions. That is because my simple hypothesis opens out to some of the most profound questions humankind has ever sought to answer, questions that have been viewed through the lens of religion, philosophy, and the scientific method. They touch on everything of any importance to human civilization and life, any life, in the universe.

In the spirit of transparency, know that some scientists find my hypothesis unfashionable, outside of mainstream science, even dangerously ill conceived. But the most egregious error we can make, I believe, is not to take this possibility seriously enough. ...

Excerpted from "Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth" by Avi Loeb. Copyright 2021 by Avi Loeb. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

For more info:

"Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth" by Avi Loeb (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), in Hardcover, Trade Paperback and eBook formats, available via Amazon and IndieboundAvi Loeb, Department of Astronomy, Harvard University

Dozens killed in Israeli airstrike on Gaza City as bombardment intensifies