The Ticket

The TicketObama warns Egypt: Are you ally or enemy?

President Barack Obama says he will decide whether Egypt is an ally or an enemy of the United States in part according to the way the fledgling government in Cairo responds to the violent assault on the American Embassy there, which happened on Monday.

"Certainly in this situation what we're going to expect is that they are responsive to our insistence that our embassy is protected, our personnel is protected," Obama said. "And if they take actions that indicate they're not taking responsibilities, as all other countries do where we have embassies, I think that's going to be a real big problem."

The president—his handling of the so-called "Arab Spring" under fresh scrutiny after attacks on American diplomatic posts in Egypt, Libya and Yemen—had been asked by Telemundo whether he sees Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi's government as an ally.

"I don't think that we would consider them an ally, but we don't consider them an enemy. They're a new government that is trying to find its way," Obama replied in what, by the standards of diplomatic talk, amounted to a blunt warning.

"They were democratically elected. I think that we are going to have to see how they respond to this incident. How they respond to, for example, maintaining the peace treaty with Israel," he added.

"So far, at least, what we've seen is that in some cases they've said the right things and taken the right steps. In others, how they've responded to various events may not be aligned with our interests," Obama said. "So I think it's still a work in progress."

Under ousted President Hosni Mubarak, Egypt benefited from close ties to Washington, including tight military-to-military relations and vast aid packages topping $1 billion per year, making Cairo one of the top recipients of American assistance. Former President George H.W. Bush in 1989 designated Egypt a "major non-NATO ally"—a status that notably makes it easier to provide a country with military hardware. (U.S. officials insisted Obama was not heralding a change in policy, but Romney supporter and former George W. Bush Middle East adviser Elliott Abrams highlighted the discrepancy.)

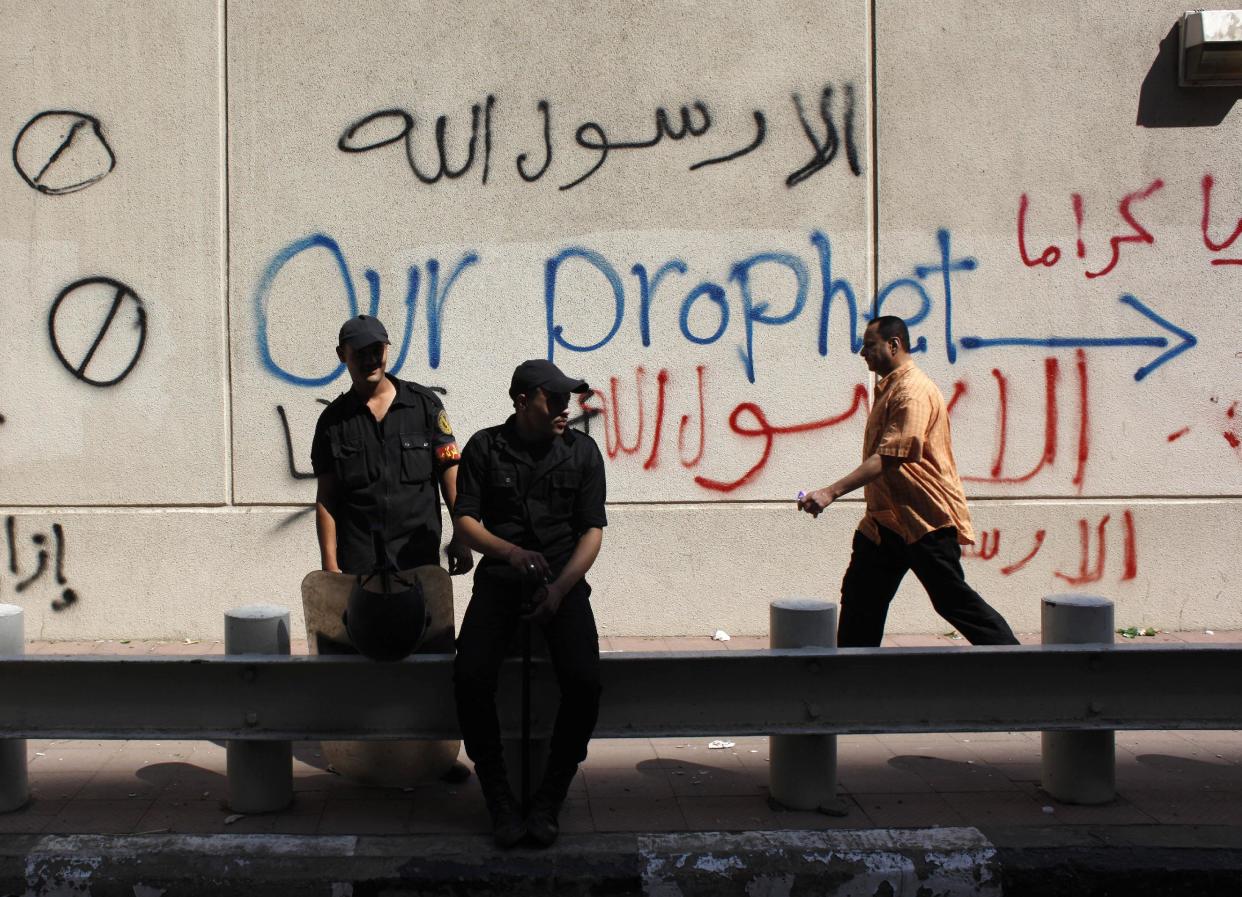

The bilateral relationship changed when Mubarak was overthrown amid mass protests, and Washington has been closely watching Morsi's government. The incident on Monday, in which demonstrators stormed the American Embassy compound and tore down the American flag, was the latest flash point—and an obvious test for both U.S.-Egypt relations and Obama's efforts to defend American interests in the volatile aftermath of the Arab Spring.

Obama and Morsi spoke by telephone on Wednesday "to review the strategic relationship" between the two countries "and our ongoing efforts to strengthen bilateral economic and security cooperation," the White House said in a statement. On Thursday, the Egyptian leader condemned the assault on the American facility.

"Given recent events, and consistent with our interest in a relationship based on mutual interests and mutual respect, President Obama underscored the importance of Egypt following through on its commitment to cooperate with the United States in securing U.S. diplomatic facilities and personnel," the White House said.

Amid concerns that an anti-Islam video on the Internet may be fueling unrest in the Muslim world, Obama "said that he rejects efforts to denigrate Islam, but underscored that there is never any justification for violence against innocents and acts that endanger American personnel and facilities."

Morsi "expressed his condolences for the tragic loss of American life in Libya and emphasized that Egypt would honor its obligation to ensure the safety of American personnel."

Obama also spoke to President Mohamed Magariaf of Libya late Wednesday, even as Americans reeled from word that the highly regarded ambassador to Libya, Chris Stevens, had been killed as a result of a raid on the consulate in that country's city of Benghazi.

"President Obama thanked President Magariaf for extending his condolences for the tragic deaths of Ambassador Chris Stevens, Sean Smith, and two other State Department officers in Benghazi yesterday," the White House said. Obama thanked Magariaf for his government's help in responding to that attack but underlined "that the Libyan government must continue to work with us to assure the security of our personnel going forward."

"The president made it clear that we must work together to do whatever is necessary to identify the perpetrators of this attack and bring them to justice," the White House said.

On the homefront, Obama waged a pitched political battle with Mitt Romney, who drew fire even from some in his party for a late-Tuesday statement in which he leveled the inflammatory charge that the Obama administration had sided with those who killed Americans. Romney essentially reiterated that accusation in a Wednesday press conference held after news of Stevens' death had become public.

But if Romney blundered with his response, the crisis highlighted the danger that sudden world events could pose to Obama's re-election bid—even in a contest most heavily shaped by the sour economy.