The imaginary connection between tax rates and GDP

The richest Americans currently pay a 35 percent tax on income over a certain threshold. This is a divisive subject between the two major parties that is sure to come up in the general election. Both Mitt Romney and Rick Santorum propose plans that would lower the rate to 28 percent. Newt Gingrich's plan includes a flat tax of just 15 percent. Obama favors returning the pre-Bush tax cut rate of 39 percent.

Proponents of lowering this rate argue that higher marginal tax rates retard productivity for the highest earners, since they are reluctant to work as hard if the bulk of their income is taxed at too high of rate. Lower the rate, the thinking goes, and the rich are incentivized to earn more, thus increasing the total tax revenue and putting more money into the economy.

Democrats point to studies like that of the Congressional Budget Office, which found that cutting income tax by 10 percent would reduce revenues by $466 billion in five years and another $775 billion in the next five years. Under the most optimistic estimates, the benefits of putting more money in people's pockets would offset 22 percent of the losses in the first five years and 32 percent in the next five, for a net loss of almost $900 billion.

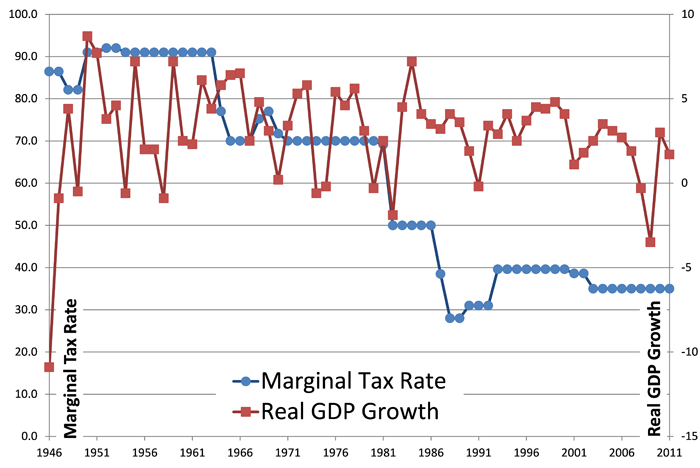

We decided to look at what the data say about the correlation between marginal tax rates and the economy. Here's a simple comparison of the marginal tax rate--that on the highest income brackets--and the rate of GDP growth or decline.

Sources: BEA and Tax Policy Center of Urban Institute and Brookings Institute

As is clear, GDP growth, the all-important measure of economic strength, does not correlate with the marginal tax rate at all. GDP growth has been both strong and weak with very high and low tax rates.

There is no question that people change their earning behavior when marginal returns vary. Right now we tax the marginal capital gain at 15 percent, a full 20 points lower than the rate for traditional income. Thus, people substitute initiatives that lead to capital gains f0r initiatives that lead to regular income. In short, the highest earners in the country are more likely to shift income between tax categories than they are to actually substitute leisure for work.

We expect politicians to over simplify the bounty that their proposals will deliver. But the data are very clear on the point that a lower tax margin for the wealthiest earners does not positively affect the GDP in any obvious way.

David Rothschild is an economist at Yahoo! Research. He has a Ph.D. in applied economics from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania. Follow him on Twitter @DavMicRot and email him at thesignal@yahoo-inc.com.

Want more? Visit The Signal blog, connect with us on Facebook, and follow us on Twitter. Handy with a camera? Join the Yahoo! News Election 2012 Flickr group to submit your photos of the campaign in action.