The Lookout

The LookoutHelen Gurley Brown: Different for nerds

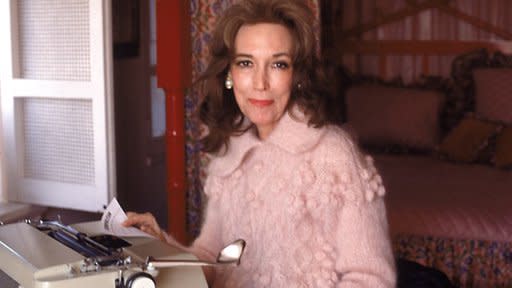

Any person willing to embody a new way of being alive in the world deserves the public's deep gratitude. It must be hell to bend yourself into an archetype, and stay there. Not to mention the hot rollers and starvation diets. Helen Gurley Brown, who died Monday, pulled it off: She transformed herself from an Arkansan hillbilly to a rich, powerful, soigné career woman and trophy wife who looked for all the world to be to the manner born.

The role Brown played, though, was never static. It was pure verb. She was always reliving that rube-to-rubies makeover, and reveling in it. As the author of close to a dozen books and the steward of the monthly pop masterpiece Cosmopolitan, Brown invented and embellished a female paradigm that inspired millions upon millions of readers to do as she had: Stop whining about not having love, husbands, sex, money, beauty or class—and buckle down, stand up straight and use your noodle to acquire them.

Brains and hard work. The Benjamin Franklin ideal, now for girls; the Edison ideal. Never rest. Forsake indulgences. As Slate pointed out years ago, Brown—who claimed to be a party girl—didn't "drink, smoke or eat." She also exercised compulsively. A Cosmo girl was supposed to follow suit and recognize that extremism in pursuit of status was no vice.

"How to Be Classy" was the Cosmo article I remember best. One page long! How simple class would be to acquire. I was 15 or 16 and studied Cosmopolitan as a highly clinical manual, a kind of Popular Mechanics for feminine wiles. Unlike more wholesome publications for girls, Cosmo never told you to take it easy or, worse, "be yourself." "Be yourself" made me physically sick. I was an anxious, self-savaging teenager, and all I wanted to know was that there was a way out of my present fix, if only I worried enough and memorized a bunch of stuff and followed instructions and worked, worked, worked.

"When you move to New York, get a good address. Fifth Avenue or Park. Even if you have to live in a closet!"

I committed this to memory.

"When you order your first drink, order the crème de la classy crème: Campari and soda."

Both tips required knowledge and self-sacrifice. That I could do. Neither required charm, beauty, family pedigree or the natural resources that the "be yourself" crowd seemed to have a monopoly on. For nerdy girls, knowledge and self-sacrifice—the kind we plow into make-work, dieting and social life at school—are the name of the game. Only later does this come to seem like the sickening thing—always keeping yourself on the hook, always imagining you can control everything. But Helen Gurley Brown lived to be 90 and never publicly renounced the worldview. She grew still more solemnly committed to it, and ever skinnier.

Sounds like a joyless, inauthentic and even terrifying way to live. But for Brown's nerdy readers the Cosmo view is, for a short time, extremely powerful. It says you don't need soul or repose, which seems so elusive anyway at that age. You can fret your way to beauty and money and love.

I lived on Fifth Avenue for a few days when I first moved to New York—crashed at a friend's beautiful apartment. I had the time of my life. And I did order a Campari and soda, telling the bartender the words I had rehearsed. It seemed promisingly purpley and fizzy, but it tasted like the acne cream Stridex, and I could hardly swallow it. On the other hand, the bartender hadn't asked for an ID. Underage rubes don't order Campari, apparently. Helen Gurley Brown had set me on my way.