Blackface is an American Coming-of-Age Ritual

If you’re searching any politician’s history for misdeeds, their younger years are a pretty good place to look. Malfeasance ranging from criminality to mischief is disproportionately committed by the young, and most people age out of particularly egregious bad behavior. But while racism tends to be more common among older people-we joke of racist grandmas and grandpas, not racist cousins-blackface seems to be a young man’s game.

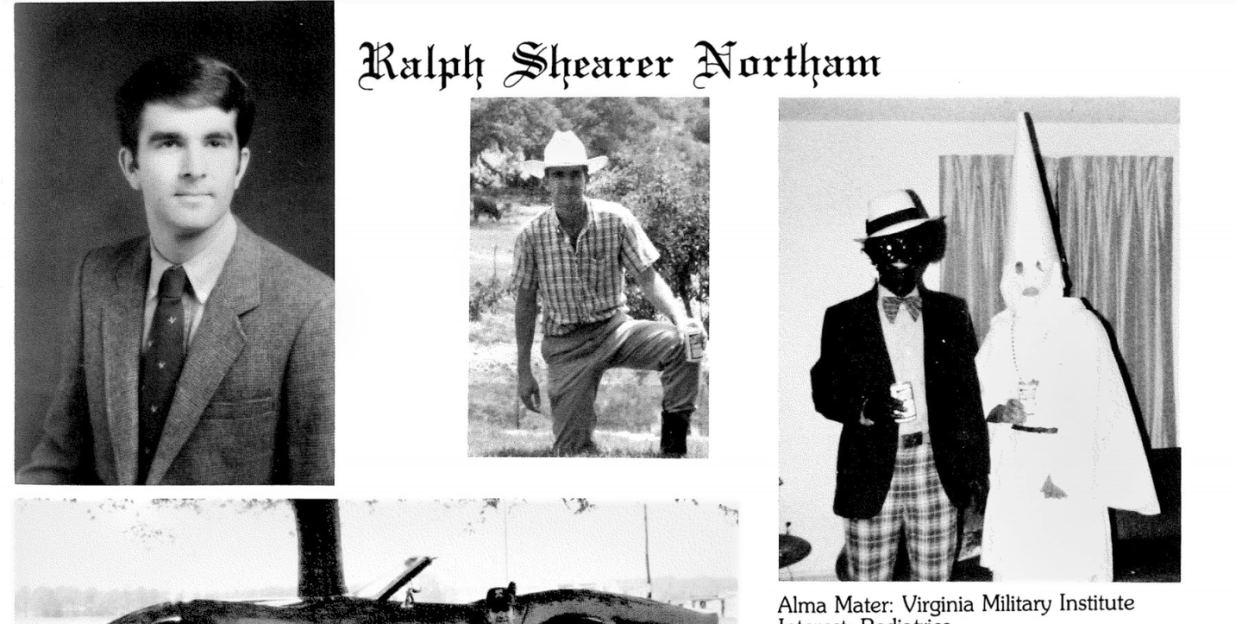

Virginia Governor Ralph Northam now denies being either the man in blackface or the KKK hood in the now-infamous photo from his medical school yearbook page, but copped to darkening his skin with shoe polish for a costume party when he was a young soldier. Third in line for the governorship, Attorney General Mark R. Herring, volunteered that he’d blacked up for a college party. And Virginia Senate majority leader Thomas K. Norment Jr. edited a high school yearbook rife with racial slurs and of course, more blackface. But the seemingly never-ending parade of scandals makes sense when blackface is considered as a historical coming-of-age rite, one that strengthens white identity through masquerades of blackness.

Minstrel shows, in which white actors blackened their faces with burnt cork and performed as black characters, peaked in popularity in the United States at the height of the Victorian Era and the industrial revolution. All the characteristics whites felt modernity had killed in them-wildness, freedom, sexual openness-were, in their imaginations, still alive in black people.

“Beyond simple mockery, the pleasure of blackface for white performers and their audiences lay in the vicarious experience of an imagined blackness,” wrote Jamelle Bouie in The New York Times, “A wild, preindustrial ‘savage’ nature that whites attributed to black Americans.”

In bestowing upon blacks their supposedly lost, backwards traits, whites placed these characteristics somewhere they could always be easily located. Blackness became an all-purpose container for delightful and dangerous sin.

And there’s no time in which the push and pull of rivaling impulses towards debauchery and maturity are stronger than adolescence and early adulthood. Young 19th century participants in Philadelphia’s annual Mummer’s Parade took to the streets in blackface, often bearing weapons and demanding free drinks from taverns. Just as the performances of the minstrel stage tended to be explicitly pro-slavery, these same young men sometimes ended their revelries by attacking Philadelphia’s free blacks. In this way, blackface provided both a respite from whiteness and an endorsement of it.

The impulses that once made blackface a massively popular art form mutated as the years passed, finding adventurous young whites heading to venues like Harlem’s Cotton Club, a Jazz Age concert hall that featured all-black performers before all-white audiences and whose institutional white supremacy was right there in its name. Listening to Duke Ellington’s band perform songs like “Jungle Jamboree” and “Jungle Nights in Harlem,” they could have a more authentic black experience than that available in a minstrel show-unaware that the entire performance was tailored to titillate white audiences, right down to the “jungle” label pushed by Ellington’s white lyricist and publisher.

These encounters with blackness-whether during the Jazz Age, the early rock ‘n’ roll years, or any of the other many eras in which white fascination with black culture hits a fever pitch-are almost always temporary. White patrons of the Cotton Club did not find themselves so enamored of black culture that they decided to abandon their old lives, move to Harlem, and try to live forever in the primitive paradise of their dreams. Instead, these encounters sent them back to the open arms of white culture. This may be why cultural tourism has historically been such an important part of adolescence and young adulthood. Adolescence is a time of identity construction, and in order to develop into the respectable adults they are expected to become, young whites can, for a time, play at being the opposite, whether this be through attending minstrel shows, evenings at the Cotton Club, or blackface-laden college parties.

While blackface itself has been verboten for a long time, no matter what Governor Northam’s former classmates might say, a safari through blackness remains an American rite of passage. It’s part of the reason why Bhad Bhabie struck such a cultural cord when she appeared on Doctor Phil; there’s no rebellion more potent than one that involves mimicking black stereotypes. Echoes of blackface were present in Miley Cyrus’s twerking phase and lightning-quick return to modesty and disavowal of hip-hop, and are present now in Ariana Grande’s blaccent and ever-deepening tan.

And while this tradition of black cultural tourism and desire to step into a black skin does have some root in a perverse admiration, one that sees in black culture inherent edginess, coolness, and sexiness, that admiration makes it no less damaging. If blackface can help a white guy be cool, it suggests that his black classmate is in a permanent state of coolness-maybe too cool to be an effective CPA. If blackface puts white people in touch with their sexuality, that suggests that a black person is inherently sexual-perhaps too sexual to fit into a family neighborhood. So while blackface seems like a form of racism that’s more misguided than malicious, it serves the insidious purpose of defining the world, trying to tell us just who black and white people are. Literary critic Leslie Fielder probably put it best. “Born theoretically white,” he wrote in 1964, “we are permitted to pass our childhood as imaginary Indians, our adolescence as imaginary Negroes, and only then are expected to settle down to being what we really are: white once more.”

('You Might Also Like',)