Black people are a small minority in Ada County. They are arrested 3.5 times more often

Black residents in Ada County are over three times more likely to get arrested than their white neighbors, according to recent police data from the county.

The research was conducted by the MacArthur Foundation as part of the Ada County Sheriff’s Office participation in the foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge, which has a goal of reducing jail and prison populations, and eliminating racial and ethnic disparities. The sheriff’s office initially applied for the grant in 2015.

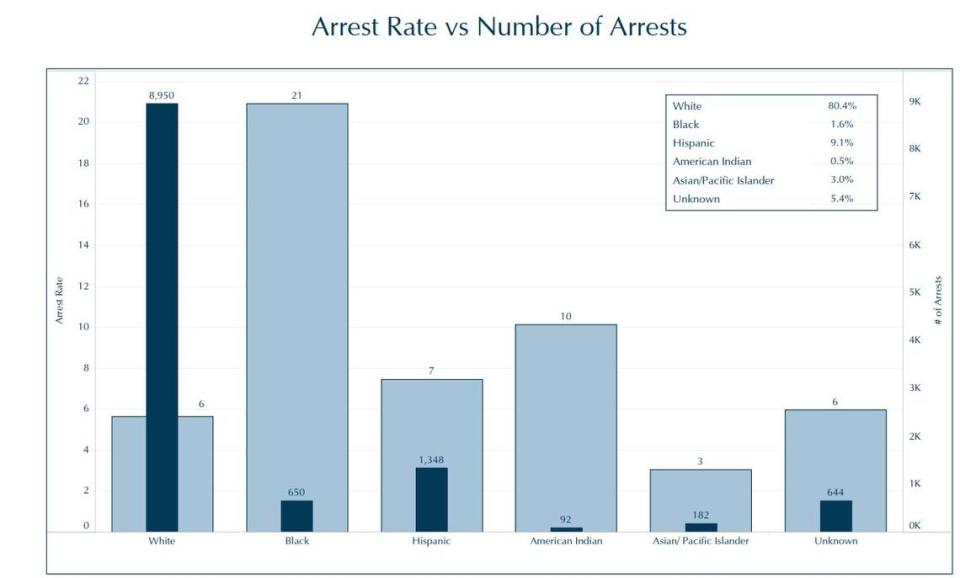

The analysis, published last year, showed that about 75% of people arrested and jailed in Ada County were white. More than 80% of the county is white, according to the U.S. Census.

But the data also showed that a much higher portion of the county’s Black population was arrested: Black adults in Ada County were arrested and booked into jail at 3.5 times the rate of white residents between 2018 and 2021. On Friday, 4.9% of inmates at the Ada County Jail were Black.

Black people make up just 1.6% of the county’s population.

Put another way, for every 1,000 white adults, six were booked into jail after an arrest, the study found. For every 1,000 Black adults, 21 were booked after an arrest. For certain crimes, the arrests become even more disproportionate.

More than 10% of the people arrested for misdemeanor battery, more than 9% arrested for resisting or obstructing officers, 8% for misdemeanor possession of a controlled substance, and nearly 7% for burglary were Black.

Native Americans were arrested and booked at 1.7 times the rate of whites, while Hispanic people were taken to jail at 1.2 times the rate of white adults.

In an interview with the Idaho Statesman, Ada County Sheriff Matt Clifford said he doesn’t believe his deputies are biased. The data is incomplete and potentially misleading, he added, and more research is needed.

“It does show that there’s a disproportionate amount of arrests in ethnicity, though it doesn’t really tell us why,” he said. “While I couldn’t tell you what’s in everybody’s hearts and heads, I could tell you what I’ve seen and heard and the actions that I’ve seen taken by other officers, and it tells me that we don’t have bias in our agency.”

Leo Morales, executive director of the ACLU of Idaho, told the Statesman that advocates have seen similar results across the country “time and time again.”

“The reality is, we continue to have issues with regards to racism and policing in the country,” Morales said in an interview. “That’s just a fact.”

The local data mirrors figures on incarceration nationwide. The Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit focused on exposing issues with mass incarceration, noted that Black Americans — who make 13% of the country’s population — comprised 38% of incarcerated people in 2019, the organization’s most recent analysis.

Clifford said the local data reveals limited information.

He said the numbers of non-white arrestees are quite small, which could lead to problems with the data if, for instance, some of the Black adults arrested had multiple arrests — another data point the report does not show.

For certain crimes, such as batteries and domestic assaults, the sheriff’s office can’t make an arrest on scene unless they saw the alleged crimes themselves. If they didn’t, they have to issue a warrant. Those warrants — which could be as high as 30% of overall arrests — aren’t shown in the MacArthur data, said Patrick Orr, a spokesperson for the sheriff’s office.

Clifford said he wants the sheriff’s office to look into whether the crimes with the most disproportionate arrests were made following calls for service, versus being initiated by an officer.

Chris Saunders, the county’s data analytics and intelligence manager, told the Statesman that sometimes a person may also get arrested once on multiple charges.

“(An officer) can be called out for one thing and it can turn into two or three others based on the circumstance,” he said. “And so in the end, it looks like there’s a lot more there when the officer is simply responding to the situation that was presented to him or her when they arrived on scene.”

Over the four-year period, the most common type of arrest by far, among all racial groups, was driving under the influence, according to the data. Next was felony possession of a controlled substance, followed by petit theft, misdemeanor battery, possession of drug paraphernalia, misdemeanor possession of a controlled substance, resisting or obstructing officers and burglary.

Boise police investigated for potential racism

In recent months, Boise hired a Washington, D.C., law firm to investigate potential racism at the Boise Police Department after it was discovered that a retired, veteran captain had authored racist posts online. The firm, Steptoe & Johnson, is reviewing department practice and data to see if racism “affected” policing.

In March, the department released video footage of a Black teenager’s arrest in November 2019, during which a Boise police officer appears to push the handcuffed teen to the ground. Interim Police Chief Ron Winegar said the officer’s conduct was “unacceptable.”

In 2017, the sheriff’s office got $1 million from the foundation to implement reform strategies. Seven people were hired by the county as a result of the grant, and each of those positions have been incorporated into full-time staff at the sheriff’s office, the clerk’s office and the public defender’s office.

What data shows about local departments

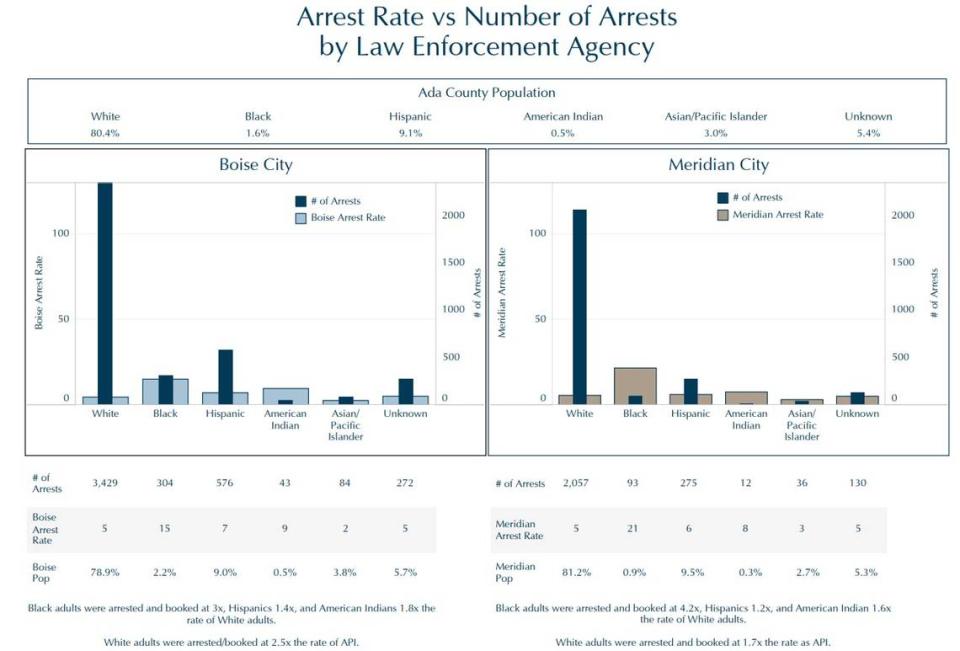

The MacArthur data also showed large disparities in the arrests performed by individual police departments.

The largest disparities appeared in the Ada County Sheriff Office’s own arrest rates, showing that Black people were arrested at six times the rates of white adults.

In Boise, Black adults were arrested at three times the rate of white people. In Meridian, Black residents were arrested at 4.2 times the rate of their white counterparts.

“Over many decades BPD has built programs and policies to address many of the concerns and goals of the report, and we are constantly working to make them better,” police spokesperson Haley Williams said in an email. She pointed out that the department has training programs and community panels to address racism, like its civil rights training, implicit bias training, liaison officers for different marginalized groups and community advisory panels.

In an emailed statement, Meridian Police Chief Tracy Basterrechea took issue with the MacArthur data analysis for leaving out other demographic factors and mentioned that his officers receive bias training.

“I strongly believe we are putting criminals in jail in Ada County and don’t believe our citizens want to see crimes increase based on some sort of social experiment, which doesn’t look at the entire picture,” he said in the email. “Regardless of color, ethnicity or socio-economic status or anything else, if you are committing crimes within the city of Meridian, we will deal with each situation accordingly.”

The MacArthur data found that the Garden City Police Department arrested Black people at 3.9 times the rate of white people, and Native Americans at 2.3 times the rate.

In a written statement, Chief Richard Allen said he does not think the data reveals bias, and that while the Garden City data was based on the demographics of the city’s residents, most of the police department’s work involves non-residents, which he indicated could skew the data.

“We must recognize that statistics are mere numbers that do not tell the complete story,” he said.

Ada County tries community engagement

Kristen MacLeod, who was initially hired by the sheriff’s office with grant funding from the MacArthur Foundation, is the office’s criminal justice and community engagement coordinator.

She created a committee of sheriff’s deputies and county staff along with community groups like the Black History Museum, the Commission on Hispanic Affairs, the Idaho Office for Refugees and Neighbors United to “create better understanding,” according to an email from Orr, the sheriff’s office spokesperson.

MacLeod told the Statesman that her office has worked with refugee organizations to try and address whether there are “barriers because of lack of cultural understanding.” Refugees make up a significant portion of Ada County’s Black population, she said.

Clifford said the department uses a program designed by the Boise Police Department that allows “certified interpreters” to be on call when language barriers crop up during police interactions. A second program allows sheriff’s deputies to connect with interpreters over the phone.

Saunders is also one of the office’s implicit bias trainers and during trainings has officers discuss their first experiences with law enforcement.

Phillip Thompson, the executive director of the Idaho Black History Museum and a member of a citizen advisory panel with the Boise Police Department, told the Statesman in a phone interview that he has “nothing but respect” for the sheriff’s office’s engagement with the museum, and that he wants to keep the communication channels open.

He also said that he is hesitant to draw conclusions about the disparities in the data, and that further analysis is needed.

“I’m a little apprehensive about asserting any causation or correlation or definitive reason as to why a disparity exists,” Thompson said. “Because I think that people have a tendency to always assume disparity means evidence of something nefarious, and more often than not, data is not that simple.”

Further data analysis Ada County is planning

Saunders told the Statesman the county wants to “go deeper” on race and ethnicity data and pull five years’ worth of data “beyond just what’s coming in the jail door.”

Some of the angles they wish to examine include: when and how officers choose to either cite and release residents or arrest them, and how many arrests are made after citizen calls versus at an officer’s initiative.

“By the time they’ve come in the door or are getting to booking, the decision’s already been made,” Saunders said. “So we want to go a step or two before that and dive into the data that’s actually taking place in the field and not just what’s coming in the jail facility.”

“What we have now, it’s totally just scratching the surface,” he said.

‘Moving away from forcing police to do community work’

Morales of the ACLU said he hopes the county continues to focus on bias in policing.

“I would hope now that a significant amount of creativity is put into efforts to resolve issues that are already within the institution of policing,” he said. “The emphasis should be to try to figure out over the next few years exactly what the plan is to make sure that we move in the right direction, because I think that any Idahoan should feel a sense of injustice for having such a disproportionality with regards to the numbers that we see in the community.”

Morales said a lot of emphasis that is put on police tactics and police presence in communities could instead be focused on other solutions.

“We should probably be moving away from forcing police to do community work,” Morales said, noting that most calls to police are not for high-level crimes. He pointed to a program in Eugene, Oregon, which sends out mental health professionals and medical workers to mental health emergencies rather than police officers.

Boise police have a Behavioral Health Response Team staffed with four employees, according to the city’s website.

Morales pointed out that bias trainings often don’t work, and that a lot of problems with policing are not about individual officers but are systemic.

“Law enforcement has two primary tools, right? They have the gun and they have handcuffs,” he said. “In many situations, those are not the best tools.”

Reporter Alex Brizee contributed.