Black community leaders raise concerns about missing persons in Kansas City metro

Nine days after a 22-year-old Black woman sought help from residents in Excelsior Springs on the morning she escaped the house of a man authorities say kept her captive for weeks, a group of about two dozen people gathered in prayer at a gas station parking lot roughly 40 miles to the southwest in Kansas City’s Marlborough Heights neighborhood.

It was a candlelight vigil for the woman who escaped, and for all missing Black women and children around the metro — including those whose cases have not been reported or highly publicized.

As details of the case have trickled out, one that has struck a chord with many in Kansas City’s Black activism circles is that the young woman reported she was picked up by Timothy M. Haslett Jr., now charged in Clay County with kidnapping and rape, somewhere on Prospect Avenue in early September. And some believe Kansas City police have been and continue to be dismissive of concerns raised by Black families and activists when it comes to people of color who go missing.

No Kansas City area law enforcement agency missing persons reports have been connected to the Haslett case by authorities leading the investigation. In a statement Monday, one week after Haslett’s arrest, Excelsior Springs Police Chief Gregory Dull said there are none “that correspond with the evidence examined so far in this investigation.”

Police have thus far kept a tight lid on information about the ongoing investigation, which is now being handled by a multi-jurisdictional team in Clay County.

Meanwhile, some Black community leaders reacted with anger to reports that the victim told neighbors that Haslett had harmed others and killed two people — and question how thoroughly those claims are being investigated.

Area residents also question whether the processes and policies of local law enforcement agencies are contributing in part to an environment where general community concerns about missing people — Black women in particular — are simply going unheard or unreported.

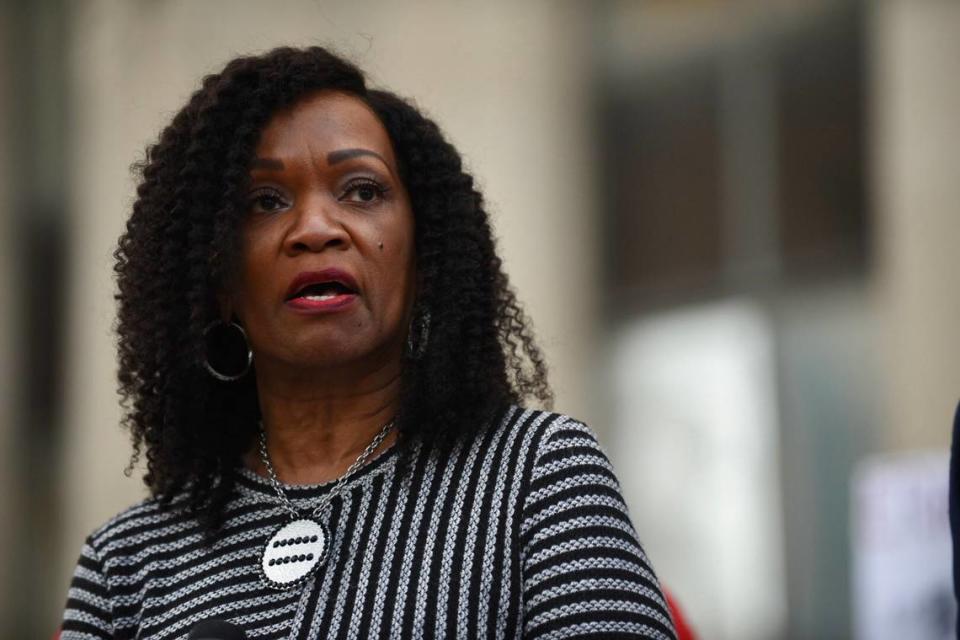

Michele Watley, founder of Shirley’s Kitchen Cabinet, an organization dedicated to empowering Black women in leadership, said concerns of missing Black women are often downplayed by police and local media in a way that is “beyond problematic and irresponsible.” She said that contributes to difficulty in the solving of missing persons cases in the Black community generally.

“With both sides of the state line - Kansas and Missouri - having been at the center of sex trafficking, there must be urgency when addressing claims of missing Black people. Because of this, our community has to be the first line of defense, keeping an eye on those we love and standing tall against the systems that fail us seemingly at every turn,” Watley said in a statement.

Gwen Grant, president and CEO of the Urban League of Greater Kansas City, said the police department has a pattern of disregarding missing persons claims, especially when it comes to Black women.

“I think that history has taught Black people: When we go missing, the system does not work the way it does for white people,” Grant said.

The police and the media pay little attention to Black women who have disappeared, she said.

That point aligns with a long-held concern among many community activists, especially those focused on Black justice and police reform.

For example, in July 2017, police declined to take a missing person’s report for Carrie Mae Blewett. Three weeks later, the 37-year-old mother of four was found dead along a tree line in the 5100 block of College Avenue. The homicide remains unsolved.

Another point of mistrust has been police shootings where the police department has put out false information or vilified the victim. Moments after detective Eric DeValkenaere fatally shot Cameron Lamb in December 2020, former Police Chief Rick Smith deemed Lamb the “bad guy.” DeValkenaere was convicted last year of involuntary manslaughter.

Rachel Riley, president of the East 23rd St. Pac Neighborhood Association, said Black and brown communities have been neglected by police for decades. One of her biggest concerns is the high homicide rate in Kansas City. Three people were killed Monday, increasing the number of homicides in 2022 to 136. This year is on track to become the second deadliest in the city’s recorded history, following a record number of killings in 2020.

‘I was looking for her by myself’

Fernando White, 42, of Kansas City, said he felt disrespected and brushed off by Kansas City police when he reported his 15-year-old daughter as missing in September. He described dropping her off at high school one morning and arriving back there that afternoon to find that she was gone.

He reported the situation during a visit to the police station. He said he was told it would be days before he would receive a copy of the report.

At one point, a GPS device his daughter was wearing was tracked to a wooded area. He said he searched that place on his own without finding her, later learning that the anklet had been removed.

As White searched for his missing daughter, he said he had a difficult time getting ahold of the detective assigned to his case. He eventually found his daughter through social media posts and tracked her to a house in Lee’s Summit.

He said he felt that he wouldn’t have gone through so many obstacles to find her if his daughter was white.

“The whole time, I was looking for her by myself,” White said.

At Sunday’s vigil, Black women were welcomed forward to speak. The event was hosted in part by the KC Defender, a Black nonprofit community media platform.

One woman stepped forward. She grew up about five minutes away from where the vigil was held near East 80th Street and Prospect Avenue, she said, and with the recent news, she’s been scared for her sisters and nieces.

“They’re afraid to go out in the streets and do anything because who knows what can happen,” she said. “You know, who knows, because the police don’t protect Black women. The media doesn’t protect Black women. It’s like we just look out for ourselves.”

KCPD missing persons policies

Under the Kansas City police department’s policy for filing a missing person report, an adult may be reported missing if the person is deemed absent from normal routines for an amount of time that knowledgeable parties think is suspicious or unusual. There is no minimum timeframe for requesting such reports be filed.

For missing or runaway juveniles, police investigating those reports are advised that such cases are considered a status offense — not a criminal one. Steps are taken to determine whether foul play is suspected, which would trigger immediate response from Kansas City’s missing persons section in such cases.

Detectives investigating juvenile runaways or missing persons are instructed to make every attempt to locate the person, including by thoroughly searching the last place the person was seen and conducting appropriate residence checks.

Reached for comment Tuesday, Kansas City police Sgt. Jake Becchina said in a statement that the department’s “relationships with our community are of the utmost value,” every investigation is taken “very seriously,” and detectives rely on people to conduct investigations.

“Missing persons investigations are undertaken the same regardless of race. We understand there will always be some in our community that are not pleased with us and we will always strive to strengthen those relationships,” Becchina said.

“We base our investigations on reports made to our department,” Becchina added, saying the department routinely displays flyers of missing persons on its social media accounts to bring attention to those cases. But he added that police “can only investigate when someone makes a report and lets us know someone is missing.”

Star reporters Katie Moore and Anna Spoerre contributed to this report.