Bipartisan effort secures funds to screen 29th and Grove residents for cancer. Now what?

For the first time in the 30 years since contaminated groundwater was discovered under several of Wichita’s historically Black neighborhoods near the Union Pacific Railroad rail yard, public money has been dedicated to screening residents for cancer.

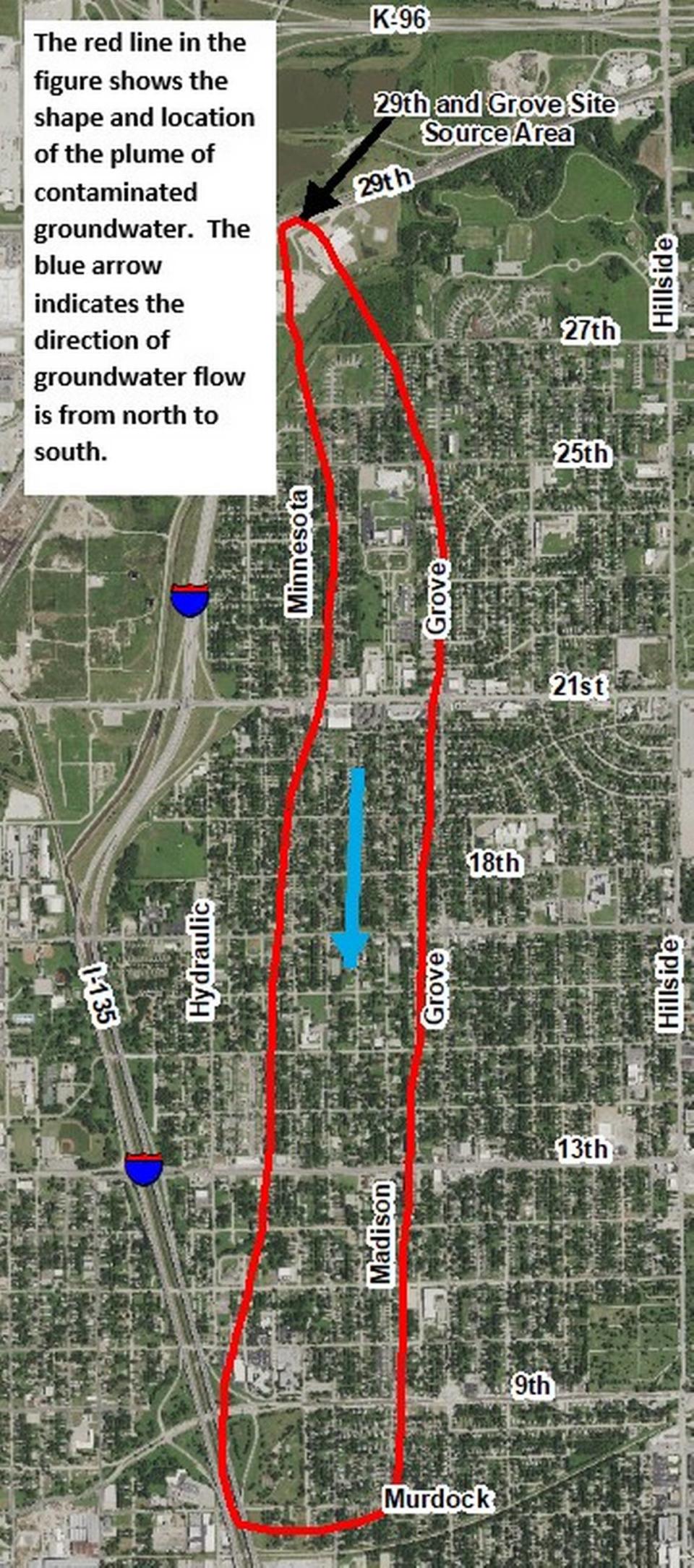

A state health study released last May found that residents living on top of the three-mile plume of trichloroethene (TCE) near the 29th and Grove spill site were more than twice as likely as other Kansans to have been diagnosed with liver cancer.

The diagnosis rate was found to be particularly high for Black residents in the nearly 2,800 affected addresses — 23.9 cases per 100,000 people compared to 10.9 cases for Black residents statewide.

Now, a collaborative effort between Gov. Laura Kelly and lawmakers from both parties has secured $2.5 million in next year’s budget to pay for health screenings for current and former residents.

The fund will support a wide variety of tests used to detect cancer, “including, but not limited to, comprehensive metabolic panels, complete blood count with differential tests, routine comprehensive urinalysis with microscopic examinations and alpha fetoprotein tests.”

“This is a very critical issue. We’re looking forward to getting testing started as quickly as possible,” Rep. Susan Estes, a Wichita Republican, said.

None of the money will go toward community outreach or paying the medical expenses of people who come in for a screening and leave with a cancer diagnosis, which could create a hardship for some residents — particularly those without health insurance.

And $1 million of the state allocation will require one-to-one local matching dollars from other public or private entities. That puts the pressure on Sedgwick County and the city of Wichita to determine how costs will be split.

“Everyone’s responsible,” said Rep. KC Ohaebosim, a Wichita Democrat who represents some of the affected neighborhoods at the Statehouse. “Now is the time to wake up and actually make sure that justice is done. And when you talk about local match, it does have to come from the city. It does have to come from the county, too.”

Union Pacific is already committed to pay for a $13.9 million cleanup plan outlined in the Kansas Department of Health and Environment’s final corrective action report for the 29th and Grove site. Remediation efforts have been underway since 2004, 10 years after the city first identified contamination in the groundwater. Experts think the chemical spill occurred in the 1970s or 80s.

The state agency’s website lists 235 active contamination sites in Sedgwick County alone.

Exposure and risks

TCE, a common solvent used to clean off paint and remove grease, can cause cancer in humans — “especially kidney cancer and possibly liver cancer and non-Hodgkin lymphoma,” according to the Environmental Protection Agency. TCE exposure occurs when a person breathes, ingests or touches the chemical.

The KDHE health study reviewed rates of other cancers among residents but only found elevated rates of liver cancer. The agency has repeatedly emphasized that there’s no way of knowing for sure if TCE exposure is responsible for the outsized number of diagnoses.

“Data doesn’t lie. If there is a higher rate of any particular cancer compared to elsewhere, you have to admit something ain’t right,” Ohaebosim said. “KDHE can’t say, ‘Well, it’s because you’re an alcoholic or a smoker,’ I mean, come on.”

Two thirds of the 66 water quality tests conducted in May 2021 found samples of more than the acceptable 5 parts per billion of TCE, including some of up to 64 times the EPA’s threshold.

KDHE hosted a public meeting about the contamination site in 2003, but afterward, state and local officials made no effort to communicate with residents about potential environmental and health risks until a November 2022 meeting, when most people in the area learned about the chemical spill for the first time and requested a health study.

Aujanae Bennett, president of the Northeast Millair neighborhood association, said her community has been “constantly disrespected, overlooked and mistreated” in the decades since the spill was discovered. She’s glad money for testing has been approved, but said it’s going to take more than that to build back residents’ trust.

“With the allocation of these funds, we’re saying that some of this money needs to be appropriated or there needs to be funding established for public service announcements and incentives for people to go and get tested,” Bennett said. “A lot of people still aren’t really aware. Everybody doesn’t have internet. Everybody doesn’t do social media.”

She said even a small incentive could be enough to encourage someone to come in for a screening at a health clinic.

“A $20 WalMart gift card makes a difference in a person’s life sometimes,” Bennett said.

Tens of thousands of people are believed to have lived in houses or apartments on top of the contaminated plume in the decades since the spill.

Rep. Henry Helgerson, a Wichita Democrat who helped shepherd funding through the fraught budget process, said the allocation is specifically for testing costs — not outreach. But he agreed that’s also worth paying for.

“We’re going to have to come up with some additional dollars somewhere in order to take care of that,” Helgerson said.

In the year since the health study was published, Hunter Health and GraceMed Health Clinic have been providing current and former residents health screenings at no cost, whether or not they have health insurance, with the expectation that state and local funding to support testing would eventually be approved.

A representative for Hunter Health said the clinic has conducted 62 health screenings for current and former residents affected by the groundwater contamination. He said the clinic could not provide any further information about patient diagnoses stemming from that testing.

A spokesperson for GraceMed said the clinic has no data on how many people have been screened and whether testing has returned new liver cancer diagnoses.

‘Whose liability is it?’

Hazel Carlis has lived in the same house in northeast Wichita for 54 years.

“When I moved into my house, I used the city water. I didn’t use well water, but some people still had their wells in the back of their yards and they were active and they were watering their grass and stuff like that,” Carlis said.

She said it isn’t very common for neighbors to share openly about their personal medical histories.

“People don’t discuss their health issues, you know what I’m saying? But there’s several people that I know that have passed away with cancer. But I couldn’t tell you what type,” Carlis said.

“The last meeting I was at, people were talking about their health issues, and more so about their parents’ than themselves. The elderly people were the ones who were affected by it the most.”

Estes said that’s why it’s so important to expand the screening effort as quickly as possible.

“I hope people are OK. But if they are not OK, there’s a lot of people who own a piece of making them whole again,” she said.

Helgerson agreed, saying it shouldn’t be entirely up to residents to pay for their own liver cancer treatment expenses in light of the heightened risk of carcinogenic chemical exposure.

“I would think that there’s going to be some discussion about whose liability is it and who should step forward in order to take care of those medical bills, either voluntarily or through the legal process,” Helgerson said.

In December, Union Pacific asked a federal judge to throw out the class-action lawsuit filed on behalf of residents of the 29th and Grove contamination site. Last month, Judge Eric Melgren dropped counts of negligence, private nuisance and unjust enrichment brought against the railroad, but ruled a count alleging Union Pacific violated Kansas’ anti-discharge law can proceed.

That law requires anyone “responsible for an accidental release or discharge of materials detrimental to the quality of the waters or soil of the state” to compensate affected property owners.

Contacted for comment, Union Pacific declined to commit any money to the local matching fund for health screenings.

“Safeguarding the health and well-being of the community has been, and remains, our top priority since we began this process over 20 years ago,” spokesperson Kristen South said in an email statement. “We initiated additional [TCE] testing within the community to re-evaluate previous results and encourage residents identified for testing to sign the access agreements and participate in this vital process.”

City and county officials contacted by The Eagle said they were still seeking clarification from the state about how local fund matching is supposed to work. Jim Jonas, Wichita’s strategic communications director, said a memorandum of understanding will be developed between the city, county and state about funding expectations and responsibilities.

In an email statement, a KDHE spokesperson declined to elaborate on the agency’s future involvement in testing efforts before funding is finalized with Gov. Kelly’s signature.

“Once the bill has been signed, we will work with state and community leaders on the best way to distribute the funding to ensure the residents are provided quality health screenings,” Communications Director Jill Bronaugh said.