Billions of dollars at stake as huge gold mine moves ahead with South Carolina expansion

Buried deep in the Lancaster County dirt are billions of dollars in gold that a mining company has been furiously digging for during the past six years.

OceanaGold’s effort has drawn praise locally for the hundreds of jobs it created, but the company also has sparked criticism over its failure to follow environmental laws, as well as the massive impact the mine has had on the landscape.

Now, however, the company has struck a deal with environmentalists that could make it easier for OceanaGold to expand from about 4,500 acres to nearly 5,400 acres.

Environmental groups agreed this month not to oppose Haile’s proposed expansion after the company pledged to put more cash in the bank to pay for pollution cleanups when the mine closes.

The deal requires the Haile Gold Mine’s owners to sock away an extra $10 million for cleanups. The deal could ultimately mean the cash trust fund would, with interest, grow to several hundred million dollars over time, say conservationists who agreed to the deal.

In return, environmental groups gave up their right to fight state and federal environmental permits the gold mine is seeking to expand operations in rural Lancaster County.

The agreement, while requiring Haile to put up more cleanup money, could lead to billions of dollars more in extra revenue for OceanaGold, the international mining corporation from Australia. The company stands to rake in about $250 million annually from the expansion, if environmental permits are issued — revenue that adds to the projected $2 billion to $4 billion the mine already stood to make from the South Carolina gold operation.

Chris DeScherer, an attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center, said he’s satisfied with the agreement his organization brokered with OceanaGold. Opposing the permits in court could have been messier and more time-consuming than signing an agreement this month with OceanaGold, he said.

Increasing cash for a cleanup ensures money will be available to fix environmental problems at the site long after the mine has been shuttered, he said. The mine is near the town of Kershaw, about halfway between Columbia and Charlotte.

“We think we are getting a better result than had we gone to court and fought this,’’ ’ DeScherer said. ”To the mine’s credit, they negotiated in good faith, they understood our concerns and I think we have put together a settlement agreement that will protect taxpayers, the environment’’ and the nearby Lynches River watershed.

Haile praised the agreement in a statement released Thursday afternoon.

“We are pleased to have worked with the conservation community to arrive at an agreement that provides additional financial assurance to the state of South Carolina, along with additional benefit to our communities in protecting ecologically sensitive land, as well as long term environmental assurances post mining,’’ the statement said, noting that government agencies that must issue permits “have a job to do and we appreciate the depth of review of this project.’’

Toxic legacies

The Haile mine is a massive operation that has transformed the wooded landscape near the town of Kershaw into an open area of gaping mining pits, piles of rocks and dirt, and waste disposal areas. Wetlands have been destroyed and creeks smothered. The mine is considered the largest in the eastern United States, rivaling the size of some western mines.

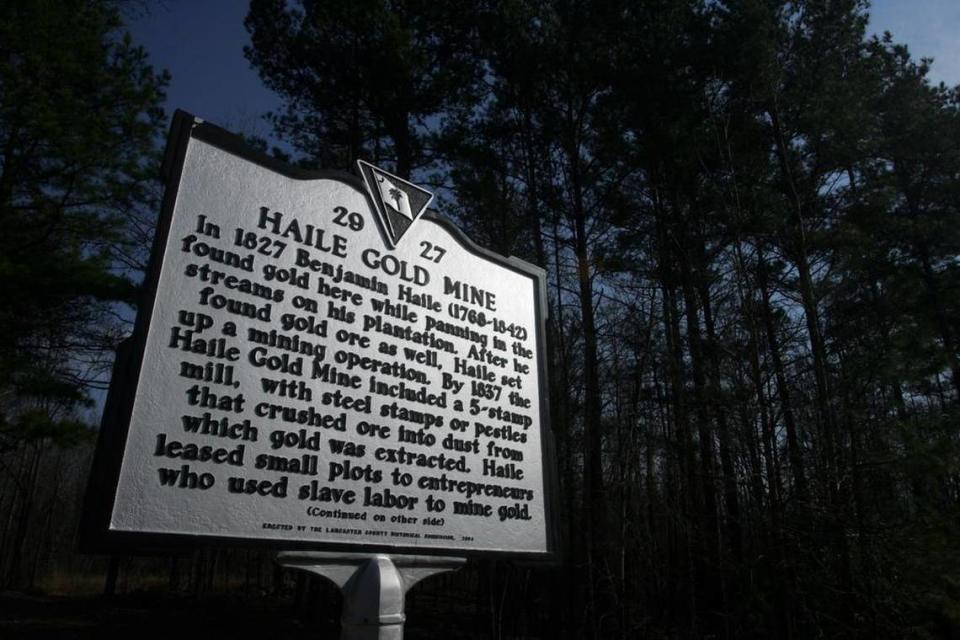

With roots dating to the early 1800s, the Haile Gold Mine had dug for gold periodically through the decades under different owners. But it reopened and dramatically expanded after finding sizable deposits of gold in the Kershaw area more than 10 years ago. The rising price of gold -- today nearly $2,000 per ounce -- has made it worthwhile for mining companies to go after tiny flecks of gold left from past mining.

The company’s agreement with environmentalists had been in the works for months. The Southern Environmental Law Center had initially led the charge against the expansion, raising questions about toxic water pollution that could linger for decades as a result of increased gold mining. Concerns also surfaced about the potential impact of a huge tailings waste pond on groundwater and people who live downstream..

Gold mines, if not properly regulated, can produce acid drainage that can contaminate creeks and groundwater for generations, The State reported in a 2014 series about the environmental impacts of gold mining. Additionally, the law center had been critical of Haile for environmental violations since it opened. State regulators have issued nearly $140,000 in fines involving the mining operation during the past two years.

The deal may not satisfy everyone. Some neighbors of the gold mine have raised concerns about noise and water pollution that they say could ruin their peaceful way of life, as well as fines levied against the Haile mine.

At the same time, environmental groups not part of the agreement, such as riverkeeper organizations, could challenge the permits. Last year, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the S.C. Department of Natural Resources also questioned the environmental impact of the project.

DeScherer and Columbia environmental lawyer Bob Guild, one of the most ardent critics of the mine, said the agreement with OceanaGold is a realistic way to deal with the environmental impacts of mining. State mining laws are not strong and an iron-clad agreement to provide more cleanup money was worth a settlement, he said.

Environmentalists relied on advice of Montana consultant Jim Kuipers, well regarded by conservationists for his expertise on mining and financial packages for cleanup work. His assistance helped make for an unusually strong deal to set aside money for cleanup, according to the law center.

Kuipers, who has for years worked on western mining issues, said opponents often fight long-running battles with mines in court that do not stop mining. In this case, Oceanagold and environmentalists came up with a compromise that kept them out of court, a deal that could help prevent long-term pollution from gold mines after they close, supporters of the deal said.

“We’re kind of painting a different picture in South Carolina than what’s been done elsewhere and it appears to be an improvement for everybody,’’ Kuipers said.

The deal not only requires Haile to put an extra $10 million into the existing $10 million cash trust account, it must also pay $4 million to the Lynches River Conservation Fund during the next four years. The Lynches River board would then appoint a person or group to find and acquire land in the area near the mine for protection. That would help compensate for the loss or deterioration of wetlands during the mine expansion.

The deal also requires Haile to notify the conservation groups of how it is complying or failing to comply with environmental laws, and it requires the company to pay for an expert to advise environmental groups about the mine. Additionally, Haile would have to make sure its operations donot hurt a nearby prison.

Environmental groups that signed the agreement with the Haile Gold Mine are the South Carolina Coastal Conservation League; the Conservation Voters of South Carolina; the Sierra Club; and the S.C. Wildlife Federation.

Also signing the deal was the regional group the Winyah Rivers Foundation. The only other large environmental group in South Carolina, Upstate Forever, was not involved in the agreement.

Weak mining law

In 2014, the Sierra Club had been the only environmental organization in South Carolina to fight a permit for the mine. After the club appealed a state mining permit, the owners at the time agreed to increase the cash trust fund cleanup payment from $5 million to $10 million. The most recent agreement to add $10 million will bring the fund total to $20 million by 2031.

Other environmental groups that had opposed the mine in 2014 eventually backed down after an agreement was reached to preserve land near the mine and protect an unusual land formation called Cook’s Mountain southeast of Columbia. Cook’s Mountain is now a state nature preserve.

Guild, a veteran environmental lawyer and attorney for the state Sierra Club, said the latest agreement better ensures a cleanup will occur in a state with a weak mining law and scores of polluting industries that have shut down without leaving enough money to cleanse sites they had contaminated.

“We knew the S.C. Mining Act was extraordinarily weak and was not going to protect us from the most serious threat: that is that once there was no more revenue, the (mine owners) would lock the gate and walk away,’’ Guild said.

Money for cleaning up environmental problems is an issue with abandoned gold mines around the country, including in South Carolina. Two abandoned gold mines, in McCormick and Chesterfield counties, are being cleaned up through the federal Superfund program. As of 2014, the public had spent $27.4 million on the sites but the cleanups were not complete, The State reported.

One of the most important parts of the new agreement, environmentalists say, is a requirement that makes sure the cash trust fund will be available for cleanup work for decades.

While state regulators could return some of the trust fund money to OceanaGold if the funds are not needed for cleanup, that can’t occur for 25 years after water quality in mining pits and ponds improves to certain state standards. That, in itself, could take years after the mine closes in the early 2030s, meaning the money would be available for cleanups until late this century, said attorneys familiar with the agreement.

The agreement helps ensure the state Department of Health and Environmental Control could not in the near future return trust fund money that might later be needed for a cleanup, attorneys for the Southern Environmental Law Center said.

“We see oftentimes that agencies are too quick to try to get money back to the regulated mining company before the risks at the sites have really been addressed,’’ law center attorney Carl Brzorad said, calling the agreement unprecedented. “So this is a really meaningful constraint on DHEC’s ability to sort of return this money, as soon as possible.’’

In addition to the cash trust fund, OceanaGold previously has pledged to put up more than $50 million through other financial mechanisms to fund cleanup and restoration work before the mine closes. Negotiations are underway to increase that bond to more than $80 million, which would bring the total financial package, including cash, to more than $100 million pledged by the company.