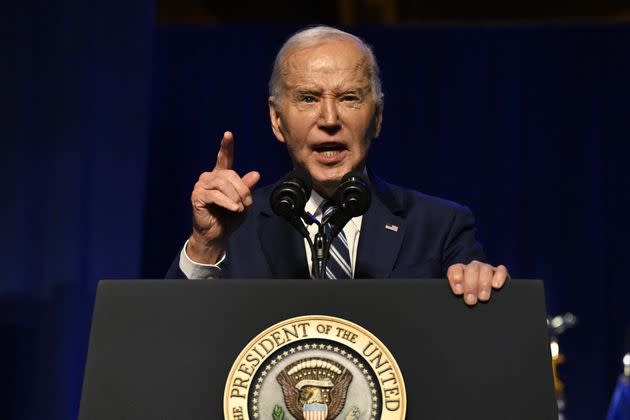

This New Biden Rule Will Save Americans $2 Billion On Utility Bills

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Biden administration has finalized a major rule change that raises the bar for real estate developers who want newly built homes to qualify for U.S. government-backed loans, laying the groundwork for a massive overhaul in the way Americans build houses.

Regulators issued a final determination Thursday that the breakthrough energy codes that dramatically increased the efficiency of new homes but caused a firestorm in the construction industry met the federal government’s standards for keeping housing affordable and slashing utility bills.

Meeting those codes is now set to become the baseline criteria for qualifying for federal loans from the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The Department of Veterans Affairs, which also issues loans, is likely to follow suit, but maintains a separate regulatory timeline.

Federal regulators expect the codes to affect at least 140,000 new homes each year and save the U.S. $2.1 billion on energy bills compared to the $605 million the stricter standards add to total construction costs.

“This long-overdue action will protect homeowners and renters from high energy costs while making a real dent in climate pollution,” Lowell Ungar, federal policy director of the watchdog American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, said in a press release. “It makes no sense for the government to help people move into new homes that waste energy and can be dangerous in extreme temperatures.”

The Biden administration’s adoption of the codes came the same day the Environmental Protection Agency finalized the nation’s first-ever limits on power plants’ carbon emissions. Combined with new rules at the Energy Department to ease permitting on transmission lines, the regulatory package was designed to put the U.S. on track to clean up the grid, meaning the electricity powering cars and stovetops in modernized homes would emit little planet-heating pollution. The announcement also came with a new rule requiring all federally owned buildings to go electric and forgo fossil fuels in new construction.

The U.S. does not set building codes on the national level. Instead, states and municipalities adopt codes written by two main third-party nonprofits, with the Washington, D.C.-based International Code Council serving as the primary author of standards for building single-family homes.

Formed out of 1990s-era consolidation of disparate code-writing organizations, the ICC convened representatives from elected governments, advocacy groups and industry associations every three years to update its codebook. The nonprofit maintained democratic legitimacy over the process by allowing only government officials to vote on the final codes at the end of the convention.

For years, it was a sleepy affair that involved mostly making minor tweaks and rubberstamping new codes with efficiency increases of 1% or less. When the ICC came together in 2019 to write the codes released in 2021, local governments were determined to make a serious dent in planet-heating emissions. Unable to dictate the cars on their roads or the power plants supplying their grid, these municipalities organized themselves to vote in favor of the most ambitious ICC energy codes in years, with efficiency gains of up to 14%.

Industry groups balked, and challenged governments’ right to vote. Siding with gas utilities, the ICC’s appeals board ultimately decided to remove key provisions that would have required new buildings to include the circuitry for electric car chargers and appliances, saving homeowners who go electric later thousands of dollars on renovations to rewire walls.

Much of the code, however, remained intact. The electoral process did not.

Bucking pressure from the newly inaugurated Biden administration, the ICC went forward in early 2021 with a plan to eliminate municipalities’ voting rights altogether. Officials from elected governments could still vote on codes governing plumbing or pools. But the energy codes that dictate insulation levels and window measurements would instead fall under a new “consensus committee” process that gave industry players more power.

The new procedure was plagued with problems from the start. But volunteers on the committee writing residential codes — including industry professionals — managed to negotiate a package of rules for the 2024 codebook. Advocates of stronger efficiency rules compromised on key components of the code, weakening the certain aspects in exchange for the industry supporting the inclusion of rules mandating the wiring for going electric.

While the 2024 code might have loosened some insulation standards from the 2021 rulebook, the new circuitry provisions promised to hasten the Biden administration’s lagging effort to promote a shift away from internal combustion engine vehicles and gas furnaces to electric cars and heat pumps. The rules seemed more ironclad this time.

When gas companies once again asked to scrap wiring rules at the end of the code-writing process last fall, the ICC’s appeals board this time sided against the fossil fuel industry, rejecting all the challenges. But last month the ICC’s board of directors defied its staff and 90% of the volunteers who helped write the code and granted the gas groups’ request.

Instead of including the circuitry provisions in the widely adopted base code, the ICC relegated the rules to a bonus-menu appendix for municipalities that wanted — and had the legal right under state law — to go further. Against the advice of ICC experts, the board of directors slapped a warning note on the appendix, suggesting that using the codes could lead to legal blowback.

Only a handful of states currently use codes that comply with the latest standards. President Joe Biden’s landmark Inflation Reduction Act included over $1 billion in aid to states to help energy regulators adopt newer codes. But the update to federal loan requirements marks the most forceful step yet the administration has taken to promote stricter codes.

Federal law from 2007 requires the U.S. government to consistently analyze and adopt the latest codes from the ICC within a year of the codebook’s latest update. But only one president so far has followed the statute — and only sort of.

In 2015, the Obama administration raised federal standards for loans to the ICC’s 2009 codes. For builders in states like Illinois, which updates its code within a year of the ICC’s release, the Biden administration’s latest move won’t do much. But meeting the 2021 codes may soon require builders in laggard states like Idaho who want buyers with access to federal loans to leapfrog more than a decade of codes.

Under that state federal statute, the Department of Energy will now be tasked with assessing whether the 2024 ICC codes improve efficiency enough to merit nationwide adoption via the criteria for U.S. housing loans. It’s unclear what outcome the process may bring.

But advocates of stricter codes want the federal government to start using the 2021 code as a benchmark for more housing loans.

Unlike mortgages backed by HUD or the Agriculture Department, loans issued under the Federal Housing Finance Agency do not set any specific criteria for energy codes. The same is true for mortgages the federally related Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac lenders purchase. In November, campaigners began pushing for those agencies to adopt similar standards to those HUD uses. The administration signaled in December it would consider the move.

Doing so would “decrease burdensome energy costs for future homeowners and renters, which in turn may help lower default risks and loan delinquency rates, and set forth a path to stabilize our shaky housing financial system,” said Jessica Garcia, senior policy analyst for climate finance at Americans for Financial Reform Education Fund.

“Implementing up-to-date energy codes will help ease the financial strain on homeowners and renters across the country as they fight to remain housed,” Garcia said. “We are encouraged by HUD’s decision, and urge the Federal Housing Finance Agency to follow suit and swiftly adopt the latest energy efficiency codes.”

Related...

Biden Is Stalling On A Rule That Would Save Americans Nearly $1.5 Billion

The ‘Scandal’ That Might Completely Upend A System America Has Relied On For Decades

A Battle Over Building Codes May Be The Most Important Climate Fight You’ve Never Heard Of

After Championing Greener Building Codes, Local Governments Lose Right To Vote

Biden Moves To Mandate Greener Building Codes In One-Sixth Of New Houses