Biden Once Rejected Trump’s Migrant Policies. Now His Ideas Echo Them

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

(Bloomberg) -- Joe Biden came into office in 2021 vowing to undo Donald Trump’s harsh policies on the US’s southern border and work with governments across Central America to reduce the motivations for their citizens to head north.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Dubai Grinds to Standstill as Cloud Seeding Worsens Flooding

What If Fed Rate Hikes Are Actually Sparking US Economic Boom?

China Tells Iran Cooperation Will Last After Attack on Israel

US Yields Spike as Hawkish Powell Puts 5% in Play: Markets Wrap

Powell Signals Rate-Cut Delay After Run of Inflation Surprises

Tapping decades of experience with the region, Biden rebuilt relationships with efforts to boost economic cooperation, not just focus on keeping migrants out. He courted new leaders, alienating some old ones.

None of it was enough.

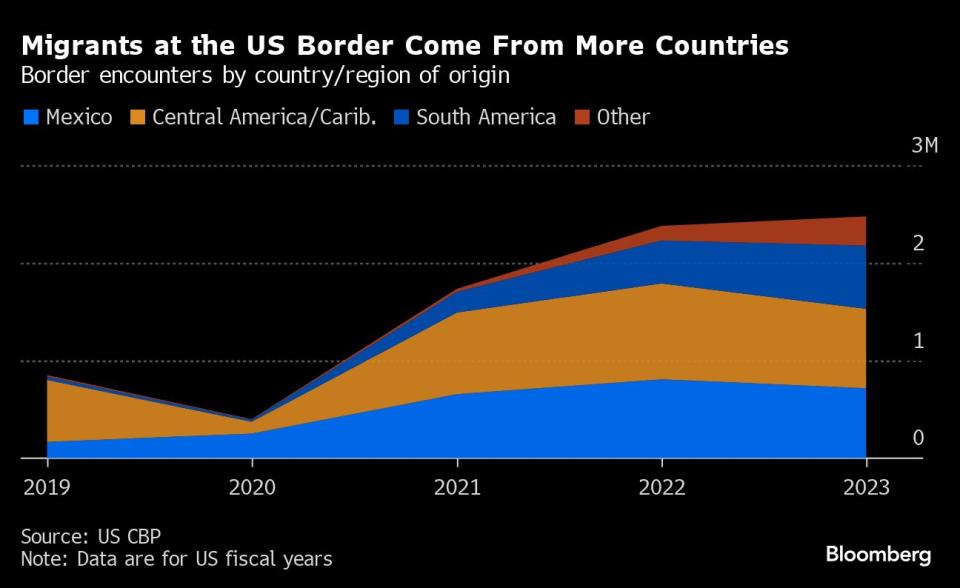

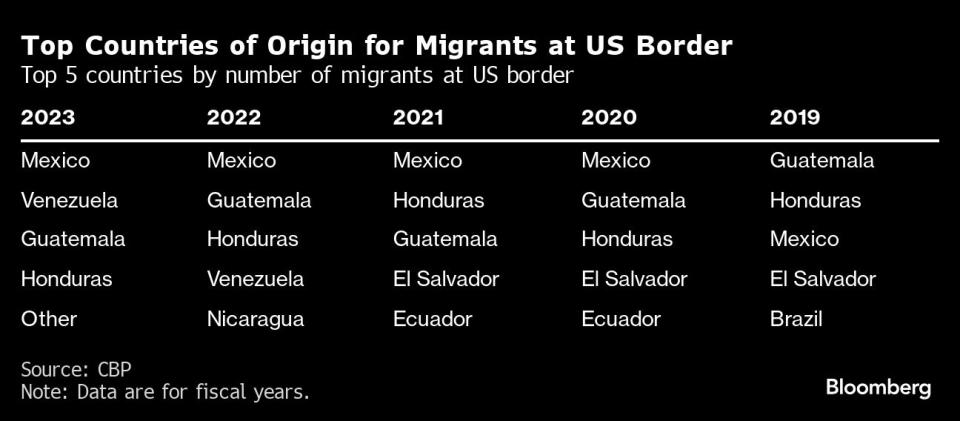

Record flows of migrants - including hundreds of thousands from countries in South America that the Biden administration hadn’t included in its aid efforts - have overwhelmed the system, turning the issue into an existential threat to the president’s hopes of reelection. With Congress stonewalling a long-overdue overhaul, Biden last week said his administration may further restrict migrants’ ability to claim asylum, echoing some of the Trump-era policies that he had previously rejected.

“The administration hoped it would have both the support of Congress on funding and time to implement that root-causes strategy, and that wasn’t the case,” said Roberta Jacobson, a longtime diplomat who helped lead Biden’s border policy in the first months of the administration.

“You suddenly had a composition of countries where migrants were coming from that went way beyond” the Central American nations the administration had targeted, she added.

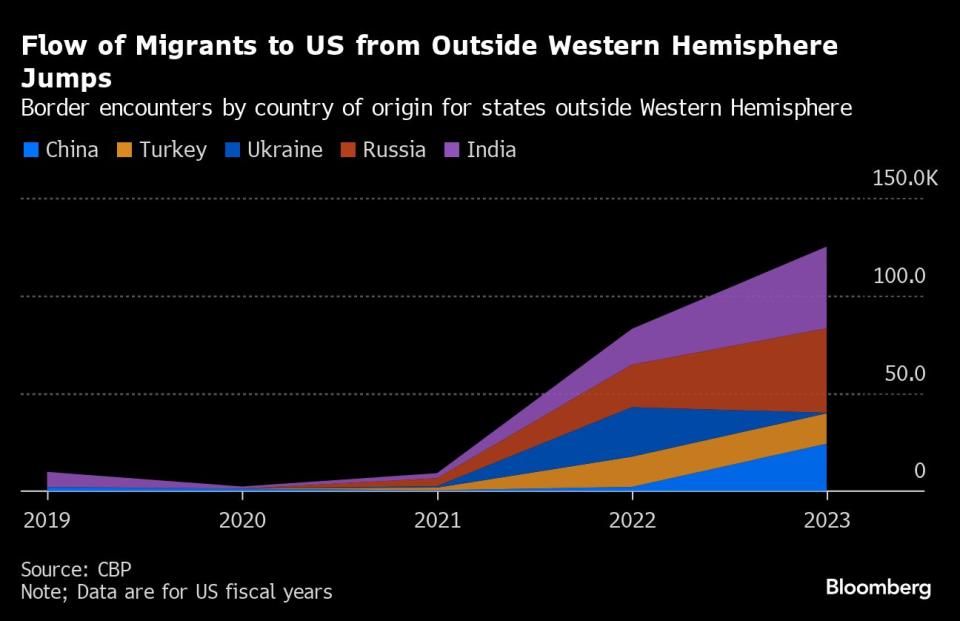

Biden administration officials argue there was no way to anticipate the extraordinary wave of migration that’s engulfed the world since the pandemic, with tens of thousands turning up at the border from as far away as China and Russia. They blame Congress for failing to approve its $4 billion aid plan for the region or deliver on any of the reforms needed to streamline the process of handling the huge numbers of people seeking to move to the US. The strong American economy has also drawn migrants looking for work and multinational criminal networks have grown to feed the flow.

The White House also points to data from the first quarter of this year, showing a decline - of almost 30%, according to US Customs and Border Protection - in the number of irregular migrants at the border compared to the previous three months.

Read more: Who Polices the Border? The Texas Battle, Explained: QuickTake

Critics argue the Biden administration has failed to follow through on some early initiatives aimed at taking the pressure off the border. Instead, Biden’s team has increasingly resorted to leaning on partners in Latin America to turn the migrants around. Some allies felt abandoned. Ambitious gambles like a deal to ease sanctions on the repressive regime in Venezuela - the no. 2 source of migrants - stumbled. With poverty and instability spreading across the region, there’s little indication the flow will slow.

The first year of Biden’s term felt like it was a series of good plans getting halted, with frequent leadership changes on the issue, according to a former official who asked for anonymity.

Administration officials reject that criticism. The work to rebuild relationships in the region has paid off in increased cooperation, though Washington always wants more, said one official. With Congress blocking aid, Vice President Kamala Harris lined up $5 billion in private-sector investment commitments for the region. Aid programs created more than 250,000 jobs in Central America, according to the White House, and migrant flows from that region have slowed.

Administration officials say they’re acutely aware of the political risks from surging migration, citing the rise of right-wing anti-immigrant parties in Europe.

But the Biden administration’s more humane approach on the border - a point of pride for a president whose own ancestors were immigrants - also helped change migrants’ perceptions, according to aid groups.

“The rhetoric has an effect,” said Juan Jose Hurtado, director of a Guatemala City nonprofit that works with migrants. “Trump created fear, and Biden’s message is less clear.”

The Biden administration knew that its less aggressive approach would draw more migrants from traditional source countries in Central America, especially after pandemic restrictions ended. To prevent that, it sought to ease the poverty, violence and misrule that led them to leave home.

“If you really want to solve the immigration challenges, you’ve got to deal with the underlying economic issues,” said Chris Dodd, a longtime ally who Biden appointed as his special adviser for the region in late 2022.

Dodd spent much of his first year in the role marshaling support for the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity, which Biden unveiled at a summit in 2022.

But that program only got off the ground in late 2023.

A network of Safe Mobility Offices set up across the region to offer migrants a lawful pathway and keep them from heading straight for the border are handling fewer cases than the administration hoped, according to the Migration Policy Institute. The White House says the system is generating strong results, with over 170,000 applications to date.

Still, aid groups say many migrants still believe the border offers their best chance for getting to the US and steer clear of the other channels Washington has set up. The growing numbers of people who’ve made it across the border and managed to eke out a living in the US have also encouraged more of their compatriots to risk the trek.

The Biden administration’s diplomatic push across the region also hasn’t always delivered results.

Despite regular courting of Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, known as AMLO, his government deported less than half as many migrants last year as the year before.

In December, Biden dispatched two rounds of top officials to Mexico City to get AMLO’s government to restore funding for deportations that had run out. One group had to endure lecturing from the nationalist leader on the superiority of Mexican family values against social ills like drug use before he agreed to dedicate more funding and make a greater effort.

“Lopez Obrador has been blackmailing the Biden administration and getting a pass on other things in exchange for what little cooperation he provides on migration,” said Veronica Ortiz, the former head of the Mexican Council on Foreign Relations. US officials disagree, pointing out that Mexico has stepped up patrols in recent months to catch migrants. A spokesperson for AMLO’s office didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Elsewhere, administration outreach has extended to leaders who might otherwise have gotten the cold shoulder were it not for their help on migration. In Guatemala, the third-largest source of migrants, the US has gambled on an outsider anti-corruption activist who won presidential elections last year. Washington steadily upped sanctions pressure on his establishment opponents - including some who’d once enjoyed US support - to block their efforts to keep him from taking office, something the US feared could spur a bigger flow of people out of the troubled country. Guatemala has been a bright spot for the administration, with its citizens showing up at the US border in lower numbers in the last two years.

But for all the efforts in Mexico and Central America, arrivals at the border from South America for the first time last year topped those from the traditional ‘Northern Triangle’ of Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala - the focus of many of the administration’s ‘root-cause’ efforts.

That was a surprise for the administration, officials said.

“We have these waves of migrants that are the product of the sometimes contradictory, stop-and-go signals the United States sends,” Costa Rican President Rodrigo Chaves said in an interview in May 2023, as his country was struggling to handle tens of thousands of migrants who’d come from further south. “Aid has been few and far between in amounts that are not very large.”

Biden later hosted Chaves at the White House and the two countries ultimately agreed on a new program to reduce the flow of migrants, diverting them to legal channels.

No place symbolizes the transformed nature of the challenge better than the Darien Gap, a stretch of roadless rainforest between Colombia and Panama linking South and Central America. For centuries, it was considered all but impassible. But last year, more than 520,000 people went through it on the way north.

“We are witnessing a constant increase,” said Ricardo Valenzuela, head of mission support at Doctors Without Borders operations in Colombia and Panama, where the group maintains two medical-assistance centers for migrants at the Darien Gap.

--With assistance from Michael McDonald and Andreina Itriago Acosta.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

A Resilient Global Economy Masks Growing Debt and Inequality

Cities Use AI to Help Ambulances and Firetrucks Arrive Faster

The Shadow Swiftie Economy Booms With Bootleg Bracelets and $1,150 Bodysuits

Top Takeaways From Businessweek’s Investigation of Teenage Sextortion

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.