Bennie Thompson applauds posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom for Medgar Evers

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

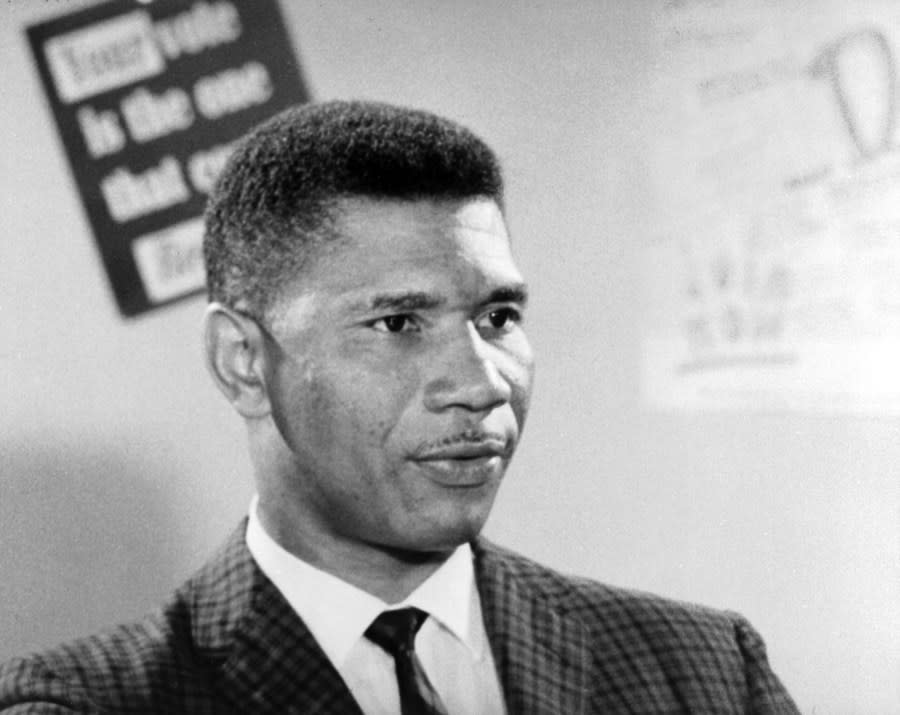

Rep. Bennie Thompson (D-Miss.) was just a boy when civil rights leader Medgar Evers was gunned down in front of his Mississippi home in 1963. But Evers’s legacy left a lasting impact on the 13-term congressman.

“I was very young when he died in his driveway, killed by a fellow who somehow saw him as upsetting the Mississippi way of life,” Thompson told The Hill.

“But for him and what he stood for, it’s kind of been a guiding light for a lot of people my age who grew up around that time,” he added. “We more or less started that aspect of the Civil Rights Movement with his assassination, as the impetus for what we were doing.”

Since his election in 1993, Thompson said he has worked to keep Evers’s legacy alive. Now, Thompson will watch as President Biden posthumously awards Evers with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Evers’s medal, Thompson said, “is a culmination of a lot of people who have supported the Medgar Evers legacy and absolutely committed to not letting it fall on deaf ears. This Presidential Medal of Freedom is the crowning jewel of keeping that legacy alive.”

“We always talk about Malcolm and Martin and Fannie Lou, what they all meant to the Civil Rights Movement in the South, but somehow some of the heroes don’t quite get their just dues,” Thompson told The Hill ahead of the ceremony.

Evers was born in Decatur, Miss., and served in the United States Army during World War II. After his military service, he attended the historically Black Alcorn State University.

His venture into civil rights began after he and a group of friends were turned away from voting at gunpoint. Soon after, Evers became president of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL) in the town of Mound Bayou, Miss. He led a boycott there of gas stations that banned Black people from using restrooms. Under his leadership, annual conferences between 1952 and 1954 in Mound Bayou attracted tens of thousands.

But one of Evers’s most famous moments followed the groundbreaking Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional.

In an effort to see if the law would be upheld, Evers partnered with the NAACP and applied to the all-white University of Mississippi Law School. He was rejected because of the color of his skin.

Evers’s activism led to federal intervention and eight years after his own application, the school admitted James Meredith. Meredith became the first African American student admitted to the University of Mississippi.

Evers would go on to recruit volunteers, lead demonstrations and organize voter registration drives for the Mississippi NAACP. He would eventually be appointed the first field secretary for the NAACP in Mississippi.

His activism cost him his life on June 12, 1963, when he was assassinated in front of his home in Jackson, Miss.

“This is a great country, but to get where we are today, unfortunately, some bad things happened,” Thompson said. “The assassination of Medgar Evers was just one of a litany of bad things. But for me — who never left the South, who never moved to work away from issues of diversity, equity and inclusion, never moved away from civil rights — it proves that with this recognition, it means that the United States of America is broadening its recognition and appreciation for all of its citizens.”

Friday’s medal was not the first time Evers’s legacy was acknowledged.

In 2003, Thompson advocated for the transfer and reburial of Evers’s remains to the Arlington National Cemetery with full honors. That same year, efforts began to create a postage stamp in honor of Evers. In 2009, the United States Postal Service released the Medgar Evers and Fannie Lou Hamer postal stamp as part of its Civil Rights Pioneers issue.

In 2015, Thompson introduced a bill to award Evers the Congressional Gold Medal. This medal was awarded in honor of his work on racial equality and his major role in the passage and enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Two years later, the home of Medgar and Myrlie Evers was designated as a national historic landmark.

In 2018, Thompson introduced the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Home National Monument Act to establish their home as a national monument and allow the National Park Service to conduct home improvements as needed.

And just last fall, Thompson and the entire Mississippi congressional delegation urged Biden to posthumously honor Evers.

“Medgar had to go to a segregated public school, he had to go to a segregated college. He basically did everything based on the fact that he was an African American, not just an American, and he was treated as a second class citizen,” Thompson said. “And he resisted that, even until the night that he was shot and killed in the driveway of his home. For that legacy and work to be recognized by the president of the United States — you can’t get any stronger than that for validation purposes.”

In addition to Evers, Opal Lee, who is often referred to as the grandmother of Juneteenth, will also be honored at Friday’s White House event.

Democratic Reps. James E. Clyburn (S.C.) and Nancy Pelosi (Calif.) are also among the 19 honorees.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to The Hill.