Belle Isle lost attractions as maintenance costs went up during decades of decline

Pony rides, canoe rentals and a public nine-hole golf course once drew visitors to Detroit’s Belle Isle Park. As the late Ernie Harwell used to say, those attractions are long gone.

The loss of those amenities and so much more from Belle Isle during the decades of Detroit’s decline set the stage for a state takeover in 2014. The Michigan Department of Natural Resources has managed the island as a state park since.

Detroit leaders bitterly opposed the state’s takeover of Belle Isle, but even city leaders admitted they no longer had the money to operate the 982-acre park. Just before the state’s takeover during Detroit’s municipal bankruptcy, the grass wasn’t getting cut, water lines were broken and even bathrooms on the island were padlocked for lack of maintenance crews to clean them.

“Belle Isle is a money pit,” said Lori Feret, a former director of the nonprofit Friends of Belle Isle group that was folded into the current Belle Isle Conservancy. “Trying to keep all the stuff up costs a lot of money. Restoring old buildings, that’s gotten highly expensive.”

Whatever else the state’s takeover was, it wasn’t a surprise. As early as 2000, the city’s new Master Plan for Belle Isle opened with a warning:

“Belle Isle is in crisis. A major effort is needed to restore Belle Isle to its prominent place as one of America’s great parks. … Valuable amenities have been lost and many more are in jeopardy. Consequently, the amenities people expect to see suffer and the island’s popularity has waned.”

The city of Detroit once offered a vast array of recreation and cultural amenities, with Belle Isle as the centerpiece. But the draining away of residents, jobs and tax base from the 1960s onward wrecked the city’s budget and its ability to maintain Belle Isle.

Detroit once operated more than 300 parks plus skating rinks and swimming pools. In 1990, the city was still budgeting $82 million for recreation and cultural activities. By 2012, it was less than $17 million and still dropping.

By the time the state-appointed emergency manager Kevyn Orr put the city into bankruptcy in 2013, the financial burden of Belle Isle was critical and onetime amenities had long since disappeared.

Among the lost attractions on Belle Isle

In 1980, a new Safariland Zoo opened covering 13 acres with more than 160 animals and elevated walkways off Central Avenue and Vista in the center of the island north of the Athletic Fields. The Safariland Zoo was closed Nov. 1, 2002. It is now abandoned and deteriorating.

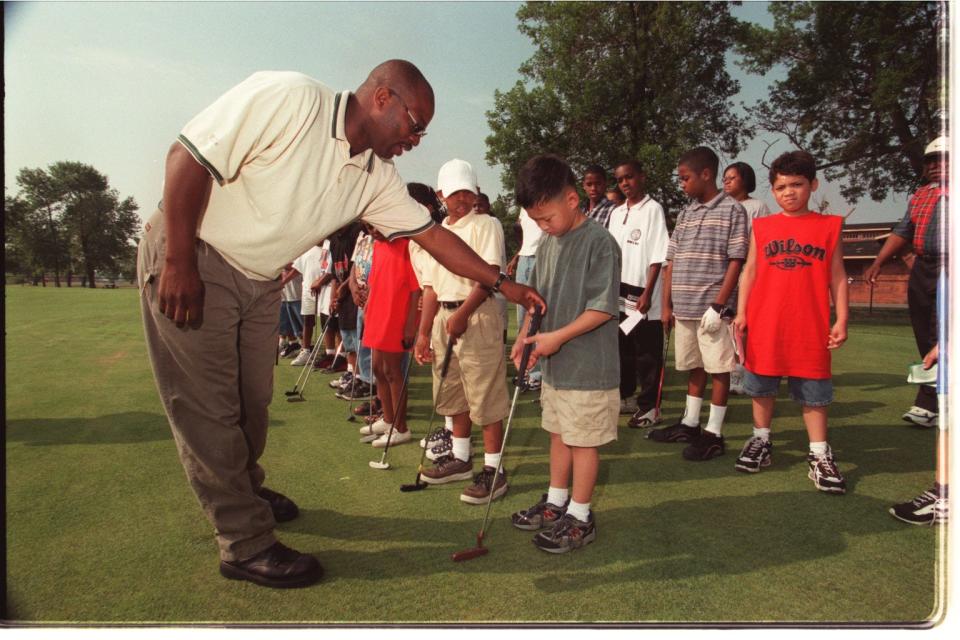

A public nine-hole golf course covering 40 acres was completed off Oakway Trail in 1922 designed by Ernie Way of the Detroit Golf Club. The course closed in 2008.

Riding stables and Shetland pony rides once drew visitors. But those attractions waned over the years. In perhaps the last gasp, the Belle Isle Riding Academy in 1977 signed a contract with the city to operate a pony ride concession. It closed in 1983.

The police station built on Belle Isle was designed by George D. Mason and Zacharias Rice and constructed in 1892-93 on Insulruhe south of Riverbank Road. In 2014, Detroit Police moved out of this building when state police began patrolling the island. The building has been deteriorating since then.

Several different canoe shelters existed on Belle Isle from the 1880s onward. Renting row boats and canoes to island visitors was popular and allowed visitors to paddle through the network of canals. The last canoe shelter sheds, opened in 1965 on the north side of the island across from the Scott Fountain, were torn down in 2005-06 and the canals have long since become too clogged for paddlers. Some kayak rentals have been added in recent years.

One piece of Belle Isle’s problems is that many of its historic buildings date to the early 20th century and now require millions in deferred maintenance.

Chief among them: The historic Detroit Boat Club building was built in 1902 but has fallen into sad disuse. The final tenant, the Friends of Detroit Rowing club, was forced to vacant in 2022 after a partial ceiling collapse. The building may now be headed to an eventual demolition.

Historic political squabbling

Patrick Cooper-MaCann, an assistant professor of urban planning at Wayne State University and an expert on Detroit’s parks, says the plight of Belle Isle wasn’t unique during the second half of the 20th century. In New York City, citizens debated how to keep Central Park and other public spaces vibrant. Similar problems existed elsewhere.

“As these cities’ finances were deteriorating, they just didn’t have the same resources they had previously. And the condition of these major parks was starting to decline,” he said.

Solutions that may have helped Belle Isle got lost in the political squabbling. At least twice, the Huron-Clinton Metroparks system offered to take over Belle Isle, but then-Mayor Coleman Young and other leaders rejected the overtures. One reason was fear of losing control of Detroit’s most popular public space to outsiders. And there were competing visions of what to do with the island.

The Metroparks system, as well as the nonprofit Friends of Belle Isle, favored a quieter, more tranquil retreat into nature. Young and many other Detroiters wanted to keep Belle Isle a spot for tailgating, family cookouts, music and lively events.

That debate continues to this day, as evidenced by the long-running disagreements over hosting the Detroit Grand Prix auto races on the island. The races moved back downtown last year.

Then, during Mayor Dennis Archer’s era in the 1990s, Archer and his recreation department head Ernest Burkeen campaigned for an entrance fee for Belle Isle to raise money for improvements. But City Council rejected the idea, fearing what a fee would mean to the countless Detroiters who used the island.

At bottom, Cooper-MaCann says, what Belle Isle needs most is a dedicated revenue source, its own tax millage. But that’s a hard sell to already-overburdened taxpayers.

“Detroit’s parks system has to compete with the police, it has to compete with the fire department, it has to compete with all the other priorities in city government,” he said. “And it’s easy to say, ‘Well, we’ll cut the grass less, we’ll cut back on recreation.’

“No one wants to raise taxes; Detroiters are overtaxed,” he said. “But cities and regions that have a dedicated park tax have better parks because they have more money. The best park systems in the country like Minneapolis have a dedicated park millage and it makes a world of difference.”

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Belle Isle lost attractions as costs went up during decline