Being married to Bernie

Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders and his wife, Jane, at a campaign rally in Manassas, Va., in September. (Photo: Cliff Owen/AP)

This story is being featured as part of our “Yahoo Best Stories of 2015” series. It was originally published in November 2015.

From the stage at the first Democratic presidential debate, nearly all the candidates opened with talk about their families.

“My wife, Hong, came to this country as a refugee from war-torn Vietnam,” said Jim Webb, who then went on to name his five children and their occupations, pausing just long enough in the middle to make viewers wonder if he was trying to remember one of them.

“My wife, Katie, and I have four great kids, Grace, and Tara, and William and Jack,” Martin O’Malley said when it was his turn, adding that his most important role was as “a husband, and a father.”

And Hillary Clinton, with all her complicated reasons not to bring up her spouse, still found a way to mention other generations and relations. “I’m the granddaughter of a factory worker and the grandmother of a wonderful 1-year-old child,” she said.

Bernie Sanders, however, didn’t pause to sketch a family portrait. In fact, he was the only one onstage who didn’t give a bio of any kind. He started right in with the “series of unprecedented national crises” that prompted his candidacy, and he never spoke of his 27-year marriage, nor the blended group of five children he and his wife consider theirs.

Sitting in the audience with two of those children, Jane O’Meara Driscoll Sanders was not the least bit surprised. Accomplished in her own right — she is, among other things, a former president of a Vermont college — she is the people person to his curmudgeon, the one who lives on the ground while he lives in his head. As her husband makes a strong national showing in the race for the Democratic presidential nomination, she remains his closest adviser, and part of her advice, on debate night as always, was that he stay focused on why he decided to run this race in the first place.

“Why should it be about me or about our family?” she said in a long and candid interview in her husband’s tiny Washington, D.C., campaign headquarters recently, dressed, as always, in casual flowing pants and blouse, her blue eyes framed by her long strawberry blond hair. “It’s about the issues. We’ve always been about the issues.”

*****

Their meet-cute was also a meet-political. In 1981, Jane O’Meara Driscoll, a recently divorced transplanted New Yorker, went to a meeting where the then mayor of Burlington was discussing a proposed tax hike that many thought would hurt low-income residents. Jane took the floor to ask some pointed questions, and when she sat down the person next to her said, “You sound like Bernie Sanders.”

“Who’s Bernie Sanders?” she asked.

He was the candidate opposing this six-term incumbent mayor, she was told, and Jane was soon working to organize a debate between the two. “He was so inspiring,” she says of her now husband at that event. “He embodied everything I believed in.”

She’d brought her then 6-year-old daughter, Carina, along, and a favorite family story is about how the little girl was the only one in the room who didn’t join in the standing ovation for her future stepfather.

“It was very clear from that night that Bernie was an astonishing person,” Carina remembers, stopping in briefly to chat during this interview. “He had the ability to really move people, and that was what drew my mother to him long before they were a couple.”

Well, not very long before. Jane and Bernie didn’t technically meet that night. She worked for his election, and they were introduced at his victory party 10 days later, after he won the race by 10 votes. Within months they were a couple.

“That was the beginning of forever,” she has said.

*****

When Jane gets tired, her children tease that her New York accent returns and “you sound just like you never left,” she says.

Born Mary Jane O’Meara in Brooklyn in 1950 (her family still uses the Mary), she grew up (like Bernie, who is nine years her senior) in Flatbush, where her childhood was defined by the chronic illness of her father. Benedict O’Meara had tripped over a sidewalk crack when Jane was 2 years old, breaking his hip, and then developed a blood infection from a deterioration of the surgically inserted pin.

Bernie and Jane in 1984. (Photo: Sanders family)

He was hospitalized for two and a half years straight, and then returned to the hospital for several months each year after that, which meant he lost his job as a schoolteacher, which had been the only income for his family of five children. When not bedridden he became a taxi driver. Jane’s mother, Bernadette, went to secretarial school at night and persuaded the Catholic kindergarten to accept Jane, her youngest, at age 3 instead of 4 so Bernadette could work during the school day. It was only 12 years later, when Jane’s older brother had built a successful business — as a blacksmith in Brooklyn (no, really) — and paid cash for the first complete medical workup their father ever had, that Benedict became well enough to stay out of the hospital for several years at a time.

“It was an awakening,” Jane says. “It was my first realization that money can buy health, and that this fact was deeply unjust.”

After graduating from Catholic high school in Flatbush, she went to the University of Tennessee at Knoxville, where she studied “marriage and children,” she says — specifically classes in marriage in the family and child development — as a sociology major. She married her high school sweetheart, David Driscoll, and left without a degree. When they moved back to Brooklyn, he worked in sales for an office supply company and she worked hourly jobs — cashier, teller — while raising two children, Heather (now a yoga instructor in Sedona, Ariz.) and Carina (a founder and owner of a Vermont woodworking school).

In the early ’70s, Driscoll was transferred by IBM to Manassas, Va., where the city girl learned to hoe fields in her ever-expanding vegetable garden and grow “actual corn.” But she chafed at the culture of a place “where the men would go after dinner and talk politics and the women would go clean up,” she says. Wanting different role models for her daughters, she urged Driscoll to ask for a transfer north, which is how she came to live in Vermont in 1975, where her youngest child, Dave (now a director of a Vermont snowboard company), was born, and where she enrolled in Goddard College — a school that to this day remains proud of its “history of creativity and chaos, invention and experimentation” — to finish her social work degree.

By the late ’70s she was divorced — amicably, she says. (“We were childhood sweethearts. We grew apart.”) In 1981 she was working for the Juvenile Division of the Burlington Police Department and volunteering at local youth centers when she attended the pivotal mayoral debate. Between that night and Election Day, Bernie created a “task force on youth” to advise his campaign and asked each of 12 local organizations to send a representative to brainstorm ways to help children and families. The youth center sent Jane, and the group selected her as chair. So she worked for Bernie before she met him.

After his election he appointed her the head of his new Youth Office, a post that reported to the city council, not the mayor, which was convenient, since romantic sparks flew more or less immediately. In that job she created programs that she believes still help keep Burlington on lists of best places to raise a family in the U.S. The office sponsored after-school programs, a municipal childcare center, a teen center, a performing arts program, and both a newspaper and local access TV show produced by students.

Her romantic dinners with the mayor usually involved talking policy and politics, and the day after their 1988 wedding the newlyweds marched together in the Burlington Memorial Day parade, then got on a plane with 10 other people for a visit to Burlington’s “sister city” in Yaroslavl, Russia, for the Sanders version of a honeymoon.

“They are a team; they always were a team,” says Carina. “They have been a really amazing example of a partnership based on building something extraordinary together.”

*****

By the time he and Jane met, Bernie Sanders had been married and divorced and had fathered a child, Levi (now a paralegal in Boston), from another long-term relationship.

After Jane’s divorce, her ex-husband went on to have another child, Nicole. All five children — Heather, Carina, Dave, Levi and Nicole — along with the seven grandchildren, are simply “family,” Jane says, “no halves or steps” about it.

Says Carina, of the man she has always called Bernie: “I’m his daughter. He’s my dad. We grew up in his house. They’re our parents.”

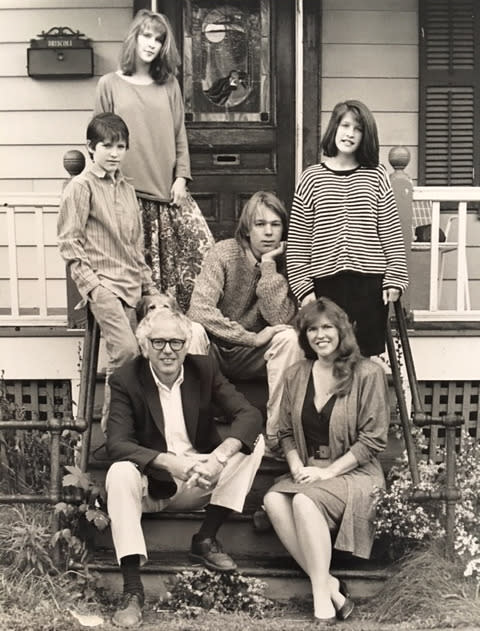

Bernie and Jane in front of their home in Burlington, Vt., in 1988 with their children, from left, Dave, Heather, Levi, and Carina. (Photo: Sanders family)

So much so that when, long after the divorce, David Driscoll was dying of lung cancer, Jane and Bernie moved him into the unoccupied condo they had bought for Bernie’s mother to live in before she died. And when Nicole was married, Bernie and Jane threw the wedding.

“Family is family,” Jane says. “We take care of each other.”

But, she adds, it’s not a family that fits neatly into a campaign bio — or the opening statement of a presidential debate.

All but the youngest of the children were at college or living on their own by the time Bernie became Vermont’s only congressman in 1991. Dave and Carina stayed in Burlington, where they were attending high school, Bernie spent weekdays in Washington and weekends back home, and Jane often shuttled between the two, having left her job with the Youth Office to help set up and run his Capitol Hill office.

That’s the constant question all Capitol Hill couples face, she says: “Do you move the family down there and lose him every weekend, or keep the family back home and only see him on the weekends, have a weekend marriage?”

In addition to forcing the couple to shuttle between homes, the new job led to a reshuffling of their partnership. “When he was mayor we just made it up as we went along,” she says. “We would say, ‘This needs to be done,’ and then we would do it. But when you come to Congress, you have to learn how does the job get done, how do the committees work, how do the party structures work?”

Jane was involved from the start, reading through resumes and hiring staff, attending the informational seminars held by the leadership on how to run a congressional office. But now when she suggested, “Why don’t we try it this way?” he often said, “Jane, this isn’t Burlington, we can’t just make our own decisions.”

It also took a while to make friends. Washington social life is a complex organism, and at first it seemed that many of the other spouses lacked the “urgency about the issues” that she felt — reminiscent of the days when the men discussed politics on the porch while the women went back inside to clean up. She often found herself drawn more to the conversation with the members than with their husbands and wives. (That changed over the years, she adds, and now she has a deep bench of friends among House and Senate spouses.)

In the first few years she was at various times her husband’s press secretary, chief of staff, and political analyst, all while working toward the PhD she would earn in sociology. (Should her husband be elected president, that would make her the first first lady to hold the title of doctor.) She was also on the board of trustees of her alma mater, Goddard College, and in 1996, when the president of that school abruptly resigned, she agreed to step in as interim president and provost. By all accounts she steered Goddard through a rocky time, helping build morale and shore up finances.

“I went in when they needed me and learned that I could do it,” she said of her 18-month tenure.

It left her wanting to do more.

She founded CEO Leadership Strategies, a political and educational consulting firm based in Burlington, but conflict of interest rules meant she needed to eventually choose between earning a living as a strategist or continuing to serve that role for her husband.

Then, in 2004 she was named president of Burlington College, a commuter school of about 200 full-time students — most of them older and with untraditional backgrounds, in other words, the kind of student she had been when she returned to Goddard for her degree. She left both her roles — at her company and as Bernie’s adviser — to take the job.

For three years she was president of a college and he was the congressman representing the state where that college was based. In 2007 he was elected to the Senate, and the dividing lines between their jobs became even more carefully defined. During her interim time at Goddard, she says, those lines had been informal because “there I was surrounded by familiar faces who knew me for decades and who knew Bernie well enough not to expect any treats from him.” But as they both grew in clout and stature, in organizations that were less familiar, “we more carefully separated our interests,” she says.

Among the rules, she says: She never spoke to members of his staff about any subject that had anything to do with the college. He almost never came to visit her at work, at most attending a few graduation ceremonies. When Burlington College applied for federal grants of any sort, its president’s name was not on the application and it would try whenever possible to pool its requests with those of other entities with similar interests in the state.

Jane is her husband’s closest adviser, and part of her advice is to stay focused on why he decided to run in the first place. “We’ve always been about the issues,” she says. (Photo: Mary F. Calvert for Yahoo News)

Despite the college’s determination to avoid conflict, however, controversy still managed to arise. One accusation that comes up increasingly often recently is that as part of Sanders’ expansion plan, Burlington College went into debt to buy a $10 million, 32-acre parcel of land for a new campus. The state agency that agreed to issue tax-exempt bonds against the loan required a commitment of several million dollars from private donors, and in listing those pledges the school included one large pledge that was a future commitment rather than money already in hand. It is standard accounting practice to count these, but in this case the payment never came through and the school now faces serious financial troubles.

The shortfall is a favorite topic of conservative websites, such as the Daily Caller, which call it deliberate loan fraud, saying it was the secret reason behind Jane’s departure from Burlington College in 2011. She calls that “nonsense,” saying that she left after seven years on the job because new board leadership came in that did not agree with her “expansive vision,” so she stepped aside. The current financial difficulties began under her successor, she says. Similarly, talk of loans and bonds and fraud didn’t come up until years after she had left, she says, when her husband began being mentioned as a possible candidate for president.

*****

When talk of the White House first began, Jane was against the idea. “Do you really want to spend all your time raising money and defending every single thing that every single one of us ever did or thought?” she remembers asking.

In her attempts to redirect, she says, “I thought of all sorts of ways he could raise the issues he felt were being ignored, but he could do that without running. Start a nonprofit. Write a book. Find other ways to steer the conversation.”

But in the end she gave her consent, and while she thought the campaign would succeed in its actual goal — not necessarily winning, but pushing other candidates to talk about things like income inequality — she and Bernie were both surprised by how fast it became so big.

That reality hit late this spring in Minneapolis, the first time the Sanders campaign drew a crowd of thousands. They were in a van, as usual, and Phil Fiermonte, the campaign field director, was driving, as usual, and as they approached the venue they saw a line snaking around the block.

“Who are we competing with, Phil?” Bernie asked, assuming that the crowd was for something, or someone, else. But it was for him.

The crowds have gotten even larger since then, yet their campaign style hasn’t changed much. Jane still travels with her husband whenever she can, because “it helps him to have a familiar face, someone he can count on.” They talk equal parts grandchildren and strategy while on the road.

Though no stranger to giving speeches herself — college presidents give a lot of them — so far Jane has stuck to shaking hands and talking to voters one on one. In a field of accomplished spouses — Kate O’Malley is a judge, Heidi Cruz is a former investment banker and Bill Clinton is Bill Clinton — she is arguably the least mentioned. She has no staff of her own. To set up an interview you call her cellphone and she answers. If you get lost on the way to the interview you call her cell again and she gives directions. Ask her where she will be the next week and she isn’t really sure, because this campaign’s schedule is a rather fluid thing.

“My daughter keeps saying I need some sort of assistant,” she says. “But it’s not about me.”

It’s about the issues, she repeats. And to watch her watch her husband on the debate stage, where he doesn’t mention her at all, is to get a glimpse of the effect his ideas had on her the first time she heard him speak.

Bernie Sanders kisses Jane before announcing his candidacy for the presidency in May. (Photo: Win McNamee/Getty Images)

“He’s doing what he aimed to do,” she gushed a few days after it was over. “The last election the candidates didn’t talk about inequality, they didn’t talk about fairness, they didn’t talk about climate change. He’s setting the agenda. That’s what it’s about.”