Behind-the-scenes look at the 9/11 memorial

To understand more about the 9/11 Memorial, look to theperson who designed it:

Ten years ago, Michael Arad was a young, idealistic architect designing police stations for the New York Housing Authority -- the kind of buildings that most people pass by and never really notice. But the World Trade Center terrorist attacks would soon stir a vision in Arad that will forever be part of America and its history.

Arad, now 42, was born in London, lived much of his childhood in Mexico and the United States, and served in the Israeli army. He had moved to New York City in 1999 from Atlanta and says he still felt like an outsider in his new hometown on Sept. 11, 2001.

On the day of the attacks, Arad was working at home when he heard on the radio that a plane had crashed into the World Trade Center. He assumed, as did thousands of others, that it was an accident.

"I remember walking across my apartment and looking through the bedroom window and seeing smoke billowing up from the North Tower," he recalls. "So I grabbed my camera and went up to the roof of the building to take a picture of that and witnessed the second plane swerve around and crash into the South Tower in this enormous fireball and explosion of glass -- a horrendous thing to behold."

He jumped onto his bicycle to go find his wife, Melanie, who worked in Lower Manhattan. "I remember that morning pretty clearly," he says. "It was almost apocalyptic, the quality of the city, biking through throngs of people, who were all transfixed and staring at the towers and wondering what was going on."

He eventually found his wife. They evacuated the downtown area, weaving through Manhattan’s urban canyons, when the towers began to crumble. "I didn’t realize the tower was falling," he recalls. "I could just hear people yelling, 'It’s falling! It’s falling!' I didn’t know what they were talking about."

The city’s response to the horrors of 9/11 affected Arad deeply. "What really struck me was how New Yorkers reacted to that day, how much courage, and compassion, and care, and love people showed in the aftermath of that attack, how people really came together to support each other in ways big and small."

There were the rallies on the West Side Highway to cheer on the recovery workers; the lines that formed around hospitals to donate blood; the makeshift memorials and candlelight vigils; the impromptu gatherings at Washington, Union, and Times squares. All of these memories and impressions flowed through Arad's growing sense of belonging.

"I think New Yorkers realized that day how much they need each other," he says. "And for me, that was really the day I felt I became a New Yorker, through the crucible of that experience."

In the months after 9/11, Arad daydreamed about a memorial for the city that would honor New Yorkers' shared sorrow and fidelity. He thought about the kind of place he would want to visit, that would nurture the community.

"I started sketching this idea, it was sort of this image in my head of the surface of the Hudson River being torn open and two square voids that the water would rush into and they wouldn't fill up," he says. "It was a very inexplicable image, something that doesn't make any sense. It just kind of stayed in my head."

He made detailed drawings and models. He then set his designs on a high shelf and went on with his life. But a couple years later, a competition to design the 9/11 Memorial was opened to the public. Arad returned to his designs and refined his concepts. He titled it "Reflecting Absence."

"I thought about my own experiences of going to Washington Square and standing around that central fountain in the presence of other people and the tremendous relief that provided," he says. "It was a way of looking at the future, not alone, but as part of a group. I stood there for a few moments in the presence of others, and that changed the way I thought about it. And I wanted to create a space like that."

For Arad, public places are vital to our lives. He points to a famous Life Magazine photo from 1945 of a sailor kissing a nurse on V-J Day in Times Square as a classic example. He also cites Tahrir Square in Cairo, the focal point of Egypt’s recent revolution.

"Public spaces are this incredible glue that binds us together as a civilization," he says. "There's nothing new about that. That's been the case for thousands of years. Increasingly today, we forget that. We try to think all this can happen in a mediated environment, like online, or in a shopping mall. It can't. We need true public places in a city."

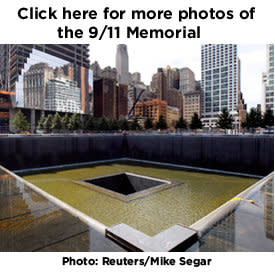

Arad’s design, which was picked in 2004 by a select jury, keeps social bonds top of mind. The two square "voids" with waterfalls fill pools that fall again into two smaller voids, all set in the original footprints of the Twin Towers. Working with landscape architect Peter Walker, Arad deepened what he calls a "permeable feeling." Trees cushion the experience, Arad explains, giving mourners comfort and a sense of calm. Visitors can approach from any number of directions, including from two streets that intersect the site.

"If this was a scar, and the fabric of the city was scarred, I felt it should be mended back to the life of the city, not erased," Arad says. "Not celebrated as a scar but allowed to heal back."

The waterfalls themselves mark the passage of time, he says, endlessly flowing into the earth. The moving water is meant to be cleansing and its sound soothing. The recessed pools are designed to allow the sky and sun to shine about.

"You walk up to the edge of these voids, you see these voids that are tangible emptiness," he explains. "It's not an emptiness that's devoid of meaning. It's an emptiness that's full of meaning. It's about the persistence of this absence in so many ways, absence of these people, absence of the towers that stood here."

The 9/11 Memorial has taken about six years to complete. Construction has entailed pitched battles between competing interests and desires. Arad has at times fought hard to preserve the spirit and tone of his original vision.

"I don’t think I had any idea of what I was about to face, what a long and difficult process it would be," he says. "At times it has been incredibly trying. But I'm very proud of the memorial we have today, and the memorial emerged through this process, through a public process."

Arad believes the back and forth has made his design better than he ever imagined. For example, insistence by Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s office that visitors in wheelchairs be able to easily see the smaller voids pushed him to devise a design with chamfered corners.

Arad is especially proud of the presentation of the victims' names, which are cut into bronze panels that hang at the waterfall edges. The 9/11 Memorial Foundation worked with all of the victims' families to place names in meaningful clusters or "adjacencies," so that one victim's name may be placed near a best friend who also perished, or neighbors who rode into work together every day are in close proximity.

"I always wanted a design that was stoic and defiant, but also quiet and respectful," Arad says. "I didn’t want a design that felt the need to scream loudly. I felt the site was freighted with so much history, anything we say here is amplified a thousand-fold."

"It's hard to come to terms with something like close to 3,000 dead in an attack," he says. "But when you hear a personal story, everyone can relate to that, to what it might be like to lose a family member, to lose a friend. I thought it was important to maintain that in the design, to find a way to amplify the nature of this collective loss through these stories of individual loss. That's what the memorial is about, individual loss and a communal loss that we all experienced together."

Just as the memorial itself captures a sense of loss and renewal, of impermanence superimposed on the immovable, Arad’s own journey since 9/11 has combined the private and the public. What started as a shared experience turned into a personal odyssey -- one that will now flow back into shared reflection.

"We found, through efforts of people at my office, my partners, the efforts of the people at the Memorial Foundation, the efforts of many family members, of people at City Hall, and many people, the challenge was always to guide it through these rough waters and bring it to completion," he says. "And we were able to do that."

Video produced by Jennie Josephson, Anne Lilburn and Jonathan Light. Production by Brad Williams, Josh Kesner, Robbie Stauder, Josh Simmons Matt Legreca, Gary Milius and Greg Murphy. Post-Production by Robert Page and John Adams. Graphics by Howard Kim for Yahoo! Studios.

Share your 9/11 memories with us on Twitter - #911remembered