What’s behind GOP lawmakers chipping away at governor’s power?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

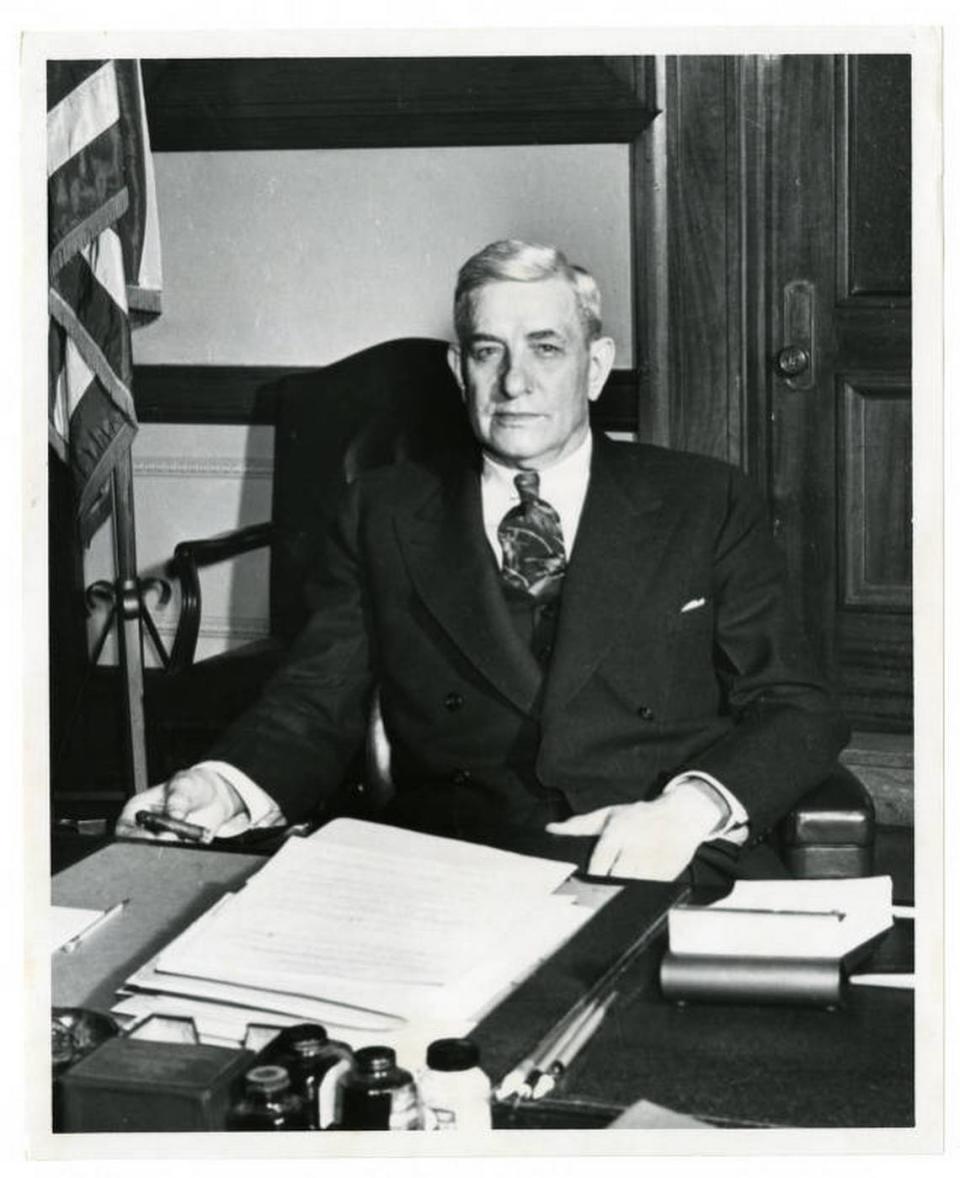

Flem Sampson and Simeon Willis aren’t names that many Kentuckians would immediately recognize. After all, they were both Republican governors in the first half of the 20th century.

Yet, that’s how far back one needs to go to find a close parallel to the Republican-controlled Kentucky state legislature’s current penchant for passing laws to diminish the office of the Gov. Andy Beshear, according to longtime Kentucky political observer and journalist Al Cross.

And they had fewer opportunities to battle with the legislature, being limited to just one term back when the legisature only met every other year.

“In history, this has almost entirely been a single legislative session phenomenon – when there was a governor of the other party and (the legislature) kneecapped him, emasculated him, defrocked him, however you want to put it,” Cross said.

Meanwhile, Beshear, a popular Democrat, is nearing the end of his fifth legislative session. Four of those five sessions have featured many bills limiting him.

Sign up for our Bluegrass Politics Newsletter

A must-read newsletter for political junkies across the Bluegrass State with reporting and analysis from the Lexington Herald-Leader. Never miss a story! Sign up for our Bluegrass Politics newsletter to connect with our reporting team and get behind-the-scenes insights, plus previews of the biggest stories.

The battle has played out on the House and Senate floors, the governor’s press conference room and in courtrooms all over the state.

Unsurprisingly, Beshear has railed against such bills limiting him during appearances with reporters. He said the Kentucky Supreme Court is “going to need to step in at some point” on them.

“If you’re gonna have three equal branches of government, which is what our separation of powers is supposed to be about, you can’t just be able to move all these things for any reason or no reason at all,” Beshear said.

Republicans have argued that Beshear has used his executive powers for political gain and particularly overextended during the COVID-19 pandemic.

But the legislature’s attempts to limit his administration have extended far past the pandemic and well into this session, where bills are being considered to strip the governor of all administration powers over the Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources, oversight on a massive grant program and appointment powers for state board of education members.

The publicly stated reasons vary.

In justifying an effort to take away both Fish & Wildlife and the Kentucky Horse Racing Commission from the governor and give oversight of the agencies to the office of Republican Commissioner of Agriculture Jonathan Shell, Senate Majority Leader Damon Thayer said Beshear has been “mucking around” with self-sustaining organizations like those because “that’s where the money is.”

The Georgetown Republican even compared Beshear to a bank robber.

A different rationale was given for a bill stripping a massive grant program – $450 million meant to help cover local funding matches for communities and nonprofits seeking federal grants, which has the potential to draw in billions – from the Beshear-controlled Department of Local Government and moving it under Shell.

When asked by Rep. Chad Aull, D-Lexington, why the program was being moved from the purview of Beshear to Shell, House Appropriations & Revenue Chair Jason Petrie argued that, technically, “we’re not moving it.”

Instead, the 2023 version of the program was under the governor and the newly created 2024 version would be placed under agriculture. In committee, Petrie said that he wasn’t sure the Department of Local Government could “pull weight” on the number of grants going through the program.

Thayer gave a blunt response to Beshear’s complaints about partisan politics.

“I don’t really care what his arguments are. We get to decide the job descriptions of the executive branch except for things that are specifically prescribed in the Constitution.”

The Court of Appeals somewhat backed Thayer up on that score, handing Beshear a loss in the ongoing battle of the branches. The court ruled in favor of the legislature and Republican executive branch officers in upholding a law taking some appointments to the Executive Branch Ethics Commission away from Beshear and to the other officers.

However, Court of Appeals Judge Sara Walter Combs wrote in a concurrent opinion that more clarity on how the legislature’s duties mix with the governor’s constitutionally-granted “supreme executive power” is needed.

The recent barrage of litigation on this critical issue convinces me that review by the Supreme Court is indeed both needed and warranted,” Combs wrote.

Why is it happening & why does it matter?

Republicans have previously groaned at the amount of grant-awarding ceremonies that Beshear has held in communities, including in the lead-up to his successful re-election effort over former attorney general Daniel Cameron.

These legislative efforts amount to a “power grab” for both Beshear and Democratic legislators alike.

“These bills are more about politics than policy, because we wouldn’t see them under a Republican governor. We need to stop trying to micromanage the administration and let Gov. Beshear do the job Kentuckians elected him to do — twice,” House Democratic Caucus Chair Cherlynn Stevenson said.

All those efforts have taken place in a context where Beshear is already quite hamstrung when it comes to providing checks and balances on the legislature.

Republicans hold four-to-one majorities in both the House and the Senate and Kentucky is one of only six U.S. states that require a simple majority to override a governor’s veto. Beshear is the only Democratic governor among those six states, all of which have Republican-led legislatures.

These factors could make Beshear one of the weakest governors in the country when it comes to shaping policy, according to Peverill Squire, a political scientist at the University of Missouri and co-author of the book “State Legislatures Today.”

“Gov. Beshear faces significant obstacles given that the GOP enjoys a supermajority and can override any vetoes with a simple majority. The simple majority override does make the Kentucky governor among the weakest governors in terms of formal powers,” Squire said.

Excluding line-item and partial vetoes, Beshear vetoed 82 Senate and House bills in his first four sessions. Seventy-two of those bills, or just over 85%, were overridden.

The most comparable governor, Squire said, is in North Carolina. While Republican majorities are much less steep than in Kentucky, they still clear that state’s three-fifths threshold to override Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper’s vetoes.

Also, Cooper can’t line-item veto appropriations bills in the same way that Beshear can.

Coincidentally or not, Beshear has already indicated that his nascent national political operation – dubbed “In This Together PAC” – will help Josh Stein, the Democrat seeking to replace a term-limited Cooper.

Before he became secretary of state, Michael Adams was general counsel for the Republican Governors Association. He guessed that he’s worked with governors in “almost all 50 states,” and he wasn’t aware of any that had faced the same political headwinds and job description limitations that Beshear has, given the size of the opposing party’s majorities and the constitutional limitations.

(Republican control the House, 80-20, and the Senate, 31-7.)

“This is not a comment on the governor personally, it’s just the office,” Adams said. “Constitutionally speaking, he is a weak governor.”

Former Democratic Gov. Paul Patton, who said he had strong relationships with legislators of all political stripes, warned the legislature may rue the day they stripped many powers from the governor.

“They ought to think a little bit further ahead. Kentucky is a Republican state, and they’re going to have Republican governors. They might want to be careful about how they limit the governor,” Patton said.

Thayer said that many of the changes to the governor’s powers are intended to be permanent and pointed to disagreements over administrative regulations and other matters the GOP-controlled legislature had with former Republican Gov. Matt Bevin.

In the specific case of taking away the Kentucky Horse Racing Commission from the governor and making it more independent, Thayer said he’s long wanted to figure out a way to make that happen.

With the backing of House Speaker David Osborne, Thayer is moving a separate piece of legislation — not tied to the Fish & Wildlife bill, which could face long odds in the House — that does just that.

Adams backs Thayer up on the matter of permanence. After former Democratic secretary of state Allison Lundergan Grimes had many powers legislated away from her in response to investigations into her use of voter data, not all of those were regained after Adams took office.

So far, the Republican legislature last year restored Adams as chair of the State Board of Elections – a politically important role – but it’s fallen short of all he’s sought. That could be the same for future Republican governors who, like he did, replace Democrats.

“The bigger you get as a party, the more factions you have, the more personalities you have and the more mouths you have to feed. So I don’t assume that the next governor, if he or she’s a Republican, is going to have smooth sailing,” Adams said.

What’s been passed?

Close to 20 bills were passed in 2021 limiting the power of Kentucky’s governor. Some of those were among the legislature’s biggest priorities, including Senate Bills 1 and 2 as well as House Bills 1 and 2, both related to the power of the governor during an emergency like COVID-19.

Other powers that session targeted include appointment powers to various boards and committees, the power to appoint a replacement U.S. Senator, authority over the department of Fish & Wildlife, administrative regulations and legal challenge venues. In that year, 27 of Beshear’s 30 vetoes were overridden.

Just two years ago, Beshear was in the legislature’s crosshairs.

Bills were passed to limit his appointments on the Executive Branch Ethics Commission, to take away the governor-appointed finance secretary’s power to name highways, to restrict anyone but the attorney general from using state funds to challenge the constitutionality of a statute and yet another to significant amount of power away from the governor in the execution of contracts.

In 2023, bills on similar topics were passed, along with a new one subjecting the state’s commissioner of education to Senate confirmation – that process is expected to play out with the board’s recent selection of Lawrence County Superintendent Robbie Fletcher as commissioner.

How we got here

Decades ago, the Kentucky governor largely called the shots when it came to moving legislation.

Before the 1970s, governors tended to have a strong say over most every important bill that got passed, the state’s budget in particular. Former governor Earle Clements once took complete control over the state budget process, and in doing so scared off his opposition in running for a U.S. Senate seat.

But the combination of a constitutional amendment and a sea change in governing style changed that dynamic sharply. In 1979, an amendment decoupling the state legislature’s election cycles with the governor’s decreased the governor’s political sway over legislators; that same year, the late John Y. Brown, Jr. adopted a much less controlling governor style when it came to his dealings with the legislature.

Another big change: When the session convened annually, which happened at the turn of the century.

Patton was governor then, recalling how the law changed without his knowledge. The bill had been dead as of 11 p.m. on the final day of session. Then he got a call from former Democratic House Speaker Jody Richards around 1 a.m.

“He called me and sort of sheepishly said ‘Governor, I think one of those bills we passed was the amendment on annual sessions,’” Patton recalled.