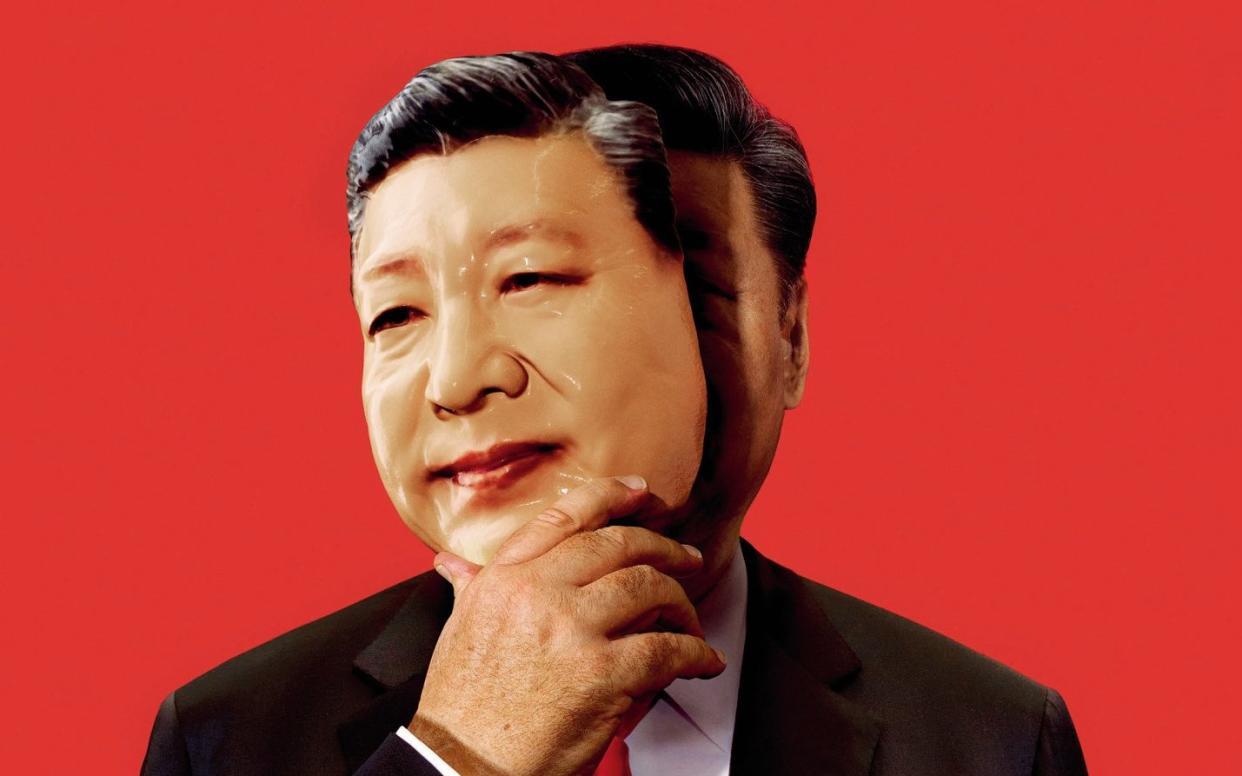

Why Xi Jinping is nothing like he really seems to the West

Xi Jinping’s first decade in power has laid bare his hyper-authoritarian doctrine. He has sidelined rivals, purged corrupt and indolent officials, and demanded unstinting loyalty from the Communist Party rank and file. He has quashed activism, silenced dissent, and built an unprecedentedly sophisticated surveillance state to assert control over society. He has padded the party’s Marxist maxims with Confucian wisdoms and rallied nationalistic fervour around one-party rule. And yet Xi, 70, has rarely given face-to-face interviews or allowed much of a glimpse into the way he operates behind the scenes.

So, how exactly did he upend decades of collective leadership and realign Chinese politics around himself? Can his autocratic turn save the party, or does it sow the seeds for future turmoil? Will he make the world safe for an increasingly authoritarian China, or return his country to the ruinous days of one-man rule?

These questions have become harder to answer – and yet ever more important in an age where decisions made in China can affect politics, business and ordinary lives just about anywhere around the world, from Wall Street and Silicon Valley to far-flung factory floors intertwined with Chinese trade.

Xi Jinping became President of the People’s Republic of China 10 years ago, in 2013, the year after being made General Secretary of the Communist Party. I spent most of the past decade piecing together answers to these questions, as a journalist covering the country since 2014 and while writing my forthcoming book, Party of One.

Analysing Xi’s own words and deeds, paired with considering contemporary and retrospective accounts from those who knew him have helped me paint a complete and complex portrait of him. They reveal a man fired with ambition and steeled by adversity; a red aristocrat who embraced his noblesse oblige and sees leadership as a birthright; a flexible apparatchik who trimmed his sails to prevailing orthodoxies; and a savvy street fighter who sidestepped scandals and exploited good fortune to carve a path to power.

Party insiders describe Xi as a micromanager. His micromanaging style has worn on many bureaucrats – and despite promises to institutionalise governance, he exerts personal influence over how policies are designed and executed – but his discipline enforcers offer daunting deterrence against dissent.

‘When loyalty is the critical measure for officials, no one dares to say anything,’ one official has said. ‘Even if the instructions from the great leader are vague and confusing about what to do.’

The recent disappearances of two high-profile ministers underscore some of the apparent consequences of Xi’s domineering leadership. Qin Gang was abruptly replaced as foreign minister in July, without explanation. Meanwhile, defence minister Li Shangfu has not been seen publicly since August, with some news reports suggesting he has been placed under investigation. Chinese officials have not formally explained what has happened to them.

While details are sparse in both cases, what is known is that both Qin and Li were hand-picked by Xi, which raises questions over the Chinese leader’s judgment and ability to choose clean and qualified officials to staff his administration. Their disappearances also reflect how China’s black-box politics have become even more opaque under Xi, who has concentrated decision-making within a tight leadership circle and places great emphasis on secrecy.

Outwardly, meanwhile, Xi projects strength and an air of Communist Party unity behind him. While mass protests against his Covid policies in late 2022 and unease over China’s sluggish post-pandemic economic recovery suggest some fraying of public trust, Xi remains firmly in control. His allies hold all significant positions of power, such as the premier, Li Qiang, who is Xi’s close confidant, and who met with Rishi Sunak last month. The party continues to call on members to uphold Xi’s authority as their ‘core’ leader. State media is filled with hagiographic depictions of Xi, which praise him for engineering China’s achievements – from alleviating poverty to promoting global development.

He is also seen as being firmly in command of challengers – a leader who has silenced dissent and enforced order in Xinjiang and Hong Kong. But the battle over hearts and minds is far from finished.

Resentment boils among Uyghurs and Hong Kongers. Efforts to propagate Mandarin Chinese among non-Han ethnic groups has fuelled bitterness among communities that the party has long regarded as model minorities, such as the Mongolian Chinese. And the sabre-rattling against Taiwan has stoked further anti-China sentiment and prompted the United States and other democracies to strengthen ties with Taipei. Xi’s efforts to modernise the military and apply its power in territorial disputes have also inflamed regional tensions and raised the spectre of armed conflict.

The backlash notwithstanding, Xi has shown no signs of letting up. Having staked his legitimacy on the promise of forging a strong and unified China, he has to deliver. He is continuing his push to modernise the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), and Chinese officials and state media often boast that the upgraded PLA could capture Taiwan with ease – ‘within three days’ one official claimed – thanks to an overwhelming superiority in troops and technology.

But the public bravado belies a circumspection that Chinese strategists often express privately about the prospects of forceful annexation. The PLA’s purpose for the time being, some say, is to deter Taiwan from declaring formal independence, a move that China would consider casus belli.

Even by Beijing’s own assessments, capturing Taiwan is a daunting task. It would feature three main phases: wearing down Taiwanese defences with aerial bombing, missile strikes, and naval blockades; amphibious landings; and pitched battles on Taiwan itself. Every stage would be fraught with difficulties, including rough seas in the Taiwan Strait, the limited number of beaches suited to landings, and the logistical challenge of transporting and protecting a massive invasion force across many miles of open water.

The exact role the US might play in direct conflict is unclear. Some analysts say Xi’s military modernisation appears to have tilted the balance in China’s favour in the Western Pacific – Beijing has been developing new weapons such as long-range ‘aircraft carrier-killer’ missiles that could keep American forces at bay.

‘Ultimately, Taiwan’s fate would depend on how the US-China strategic competition plays out,’ says Lee Hsi-min, a retired Taiwanese admiral. A critical question is whether the Communist Party would use force to secure its vision of a unified China, a decision that – under current circumstances – would fall to one man.

‘Beijing prefers peaceful unification, and military means are the last resort, but we cannot really know what Xi is thinking,’ Lee warns. ‘Never say never.’

Xi Jinping’s own upbringing sheds some light on his approach. His father, Xi Zhongxun, a revolutionary and senior official, was purged by the leadership in 1962 for allegedly leading an anti-Party clique that sought to seize power. Worse was to follow after the Cultural Revolution began in 1966, when Xi was turning 13. He would be jailed three to four times during the early years of that tumultuous decade, with Red Guards threatening to execute him, he recalled decades later.

‘Because I was stubborn and unwilling to be bullied, I offended the rebel faction,’ Xi told a state-run magazine in 2000. ‘Anything that was bad was blamed upon me; they thought I was a leader.’

It taught Xi the brutality of politics – and the inner workings of what it means to be in power. ‘People who have little contact with power, who are far from it, always see these things as mysterious and novel,’ he has said. ‘But what I see is not just the superficial things… I see… how people can blow hot and cold. I understand politics on a deeper level.’

His first wife, Ke Xiaoming, is the daughter of China’s former ambassador to the UK. But the couple drifted apart and fought ‘almost every day’, according to a longtime friend, who said Xi and his wife divorced when he refused to go with her to England. Official biographies of Xi are silent on this marriage.

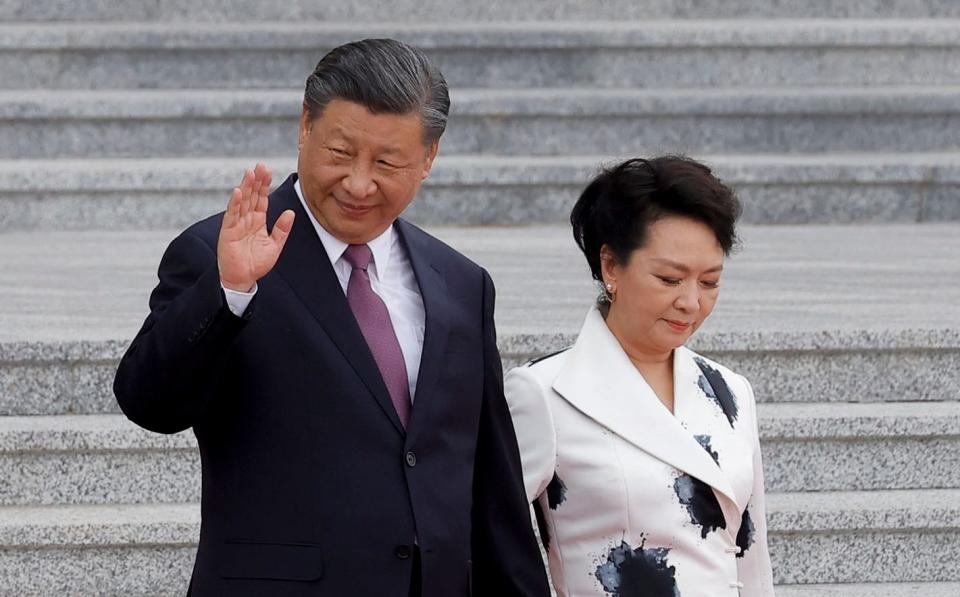

It was his second marriage that reinforced Xi’s military connections and added a dash of glamour to his staid image. Peng Liyuan, a popular folk singer, who is nine years his junior, was far more famous than he was when they met in late 1986, introduced by friends.

Peng wore military pants to test how much her date valued appearances – but he surprised her. Rather than the usual quizzing about her latest hits, he asked an almost academic question about the number of ways to perform vocal music.

‘I’m very sorry, I watch very little television. What songs have you sung?’ Xi asked later.

When they married in September 1987, it was with little fanfare. As Xi’s national profile grew in the 2000s, Peng became his advocate, lauding him in interviews as a loving spouse and doting father to their daughter and only child, Mingze. She took on a limited role in politics, becoming a member of a government advisory body and a goodwill ambassador for HIV/Aids prevention. Within elite circles, she often presented herself as a face of the family, even speaking on her husband’s behalf in private engagements.

In Xi’s own words, as well as the words of those who knew him, his ambitions led him not to wealth, but to power. ‘Going into politics means one cannot dream of getting rich,’ he once said.

As Communist Party chief, Xi named himself head of committees that oversaw key portfolios including economics and finance, national security, foreign affairs, legal affairs and internet policy. He installed close confidants and trusted associates in key positions and undermined rivals with hollow promotions to roles with little authority or by switching their portfolios to separate them from their power bases. In some instances, Xi neutralised potential opponents by purging their aides and supporters through disciplinary probes.

People familiar with this describe a discreet and meticulous process, where Xi would ask trusted disciplinary inspectors to quietly prepare dossiers – often running to hundreds of pages – on senior officials he wished to undermine. Xi would also authorise investigations against the officials’ close associates, as a way to dismantle their political networks and neutralise any latent threat they posed.

Even Wang Qishan, one of Xi’s oldest friends and the party’s anti-corruption chief from 2012 to 2017, wasn’t beyond reach. In recent years, party investigators have scrutinised some of Wang’s associates and, in a number of cases, taken them down with criminal probes.

Meanwhile, access to Xi became harder to attain. He once told foreign dignitaries that he didn’t have a mobile phone, which meant that most people – apart from his closest advisers – could only reach him through carefully screened meetings, phone calls and written submissions.

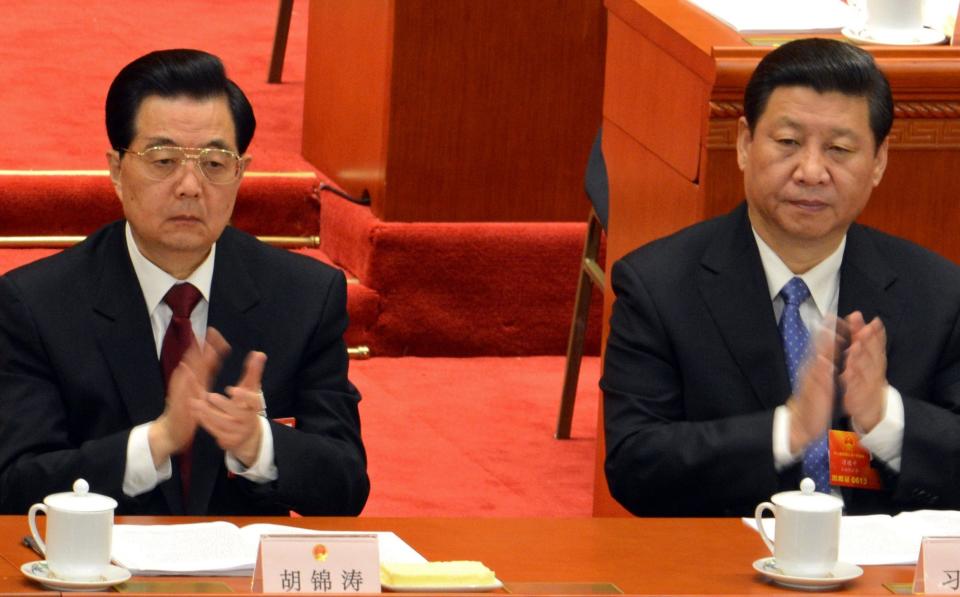

When Xi first vowed to cleanse the party in 2012, many officials thought he was following a well-worn playbook: conduct a short and sharp campaign to consolidate power in the name of fighting graft. But Xi unleashed a veritable bloodbath. The party has punished more than 4.6 million people in the decade since Xi took power. Some 627,000 people were punished in 2021 alone for disciplinary violations – nearly four times the total in 2012, the last year of Hu Jintao’s leadership.

‘Corruption is a cancer of society,’ he told top Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) officials in 2013. ‘If the scourge of corruption worsens, eventually the party and the nation will be ruined.’

Xi has kept up his long-running disciplinary crackdowns this year, allegedly purging corrupt and negligent officials across China’s medical, finance and sports industries, among others, and even some of the very enforcers tasked to police party discipline.

But myth making has been an equally important component of Xi’s push for preeminence – his public image is clearly a priority.

‘I have many hobbies, the biggest of which is reading. Reading has become a way of life for me,’ Xi told reporters in 2013, weeks after becoming President, after name-checking eight Russian writers – including Chekhov, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy – whose works he claimed to have read.

Two months later, Xi charmed Greece’s Prime Minister by saying he read many works by Greek philosophers during his teenage years. When Xi visited France the following year, he boasted about reading Montesquieu, Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot, Sartre, and more than a dozen other writers. State media feted Xi as an erudite leader, publishing lists of his favourite books and cajoling citizens to emulate his love for learning.

The publicity blitz set tongues wagging among Xi’s fellow ‘princelings’, as descendants of revolutionary leaders and senior officials are known. Many among them concluded that Xi’s outlandish claims of literary prowess betrayed deep-seated insecurity about his lack of a formal education – particularly in contrast with Mao, who wrote poetry.

‘Xi is not cultured. He was basically just an elementary schooler,’ one princeling who has known Xi for decades told me. ‘He’s very sensitive about that.’

Few people, if anyone, and possibly not even Xi himself, know how long he wants to stay in power. Nor has he made clear if, when or how he would designate an heir. Xi may have a timeline in mind, but changing circumstances could force him to rethink those plans. The uncertainty keeps the party elite on their toes, helping Xi maintain control and buying him time to assess potential successors.

Since becoming party chief in 2012, Xi has accrued personal clout to a degree unseen since Mao. He designated himself the party’s ‘core’ leader and greatest living theorist, ensuring that he would remain China’s preeminent politician until he passes on, or as party insiders say, ‘goes to see Marx’. He scrapped term limits on the presidency, and upended retirement norms honed by his predecessors – obliterating the most important political reforms of the post-Mao era.

When Xi embarked on a whirlwind tour of Italy, Monaco, and France in early 2019, his hosts feted him with ceremonial welcomes and state banquets – lavish pageantry designed to boost his image as a statesman. For some observers, however, it was his unusual gait that caught the eye.

Television footage showed Xi walking with a slight limp while inspecting guards and touring local sights. At a meeting with French President Emmanuel Macron in the city of Nice, Xi gripped both arms on his chair to ease himself into his seat. The images stirred much speculation on Twitter and in overseas Chinese media, with theories ranging from muscle sprains to gout. Elsewhere, in private social-media chat rooms, some Chinese academics also gossiped about the President’s health. A retired politics professor in Beijing told me, ‘Everyone didn’t say much, but there was a tacit mutual understanding.’

During a 2020 speech in Shenzhen that was broadcast live, Xi repeatedly coughed and stopped to drink, prompting state television to cut away from him and show the audience instead – an episode that sparked further online chatter.

Like many authoritarian one-party states, China lacks clear procedures for filling unplanned vacancies in top posts. The risk is that the party of Xi may be so driven by his personality that few of his potential successors could command it effectively in his absence.

Xi promised to build a system that could transcend China’s feudal past, restore its glories, and seal his place among history’s greatest statesmen. But his new-look Communist Party has come to resemble, in some ways, the imperial bureaucracies of old – bigger and better organised, but no less autocratic, rigid and plagued by woes about succession.

Just as leaders have died and their governance ended throughout Chinese antiquity, Xi may have become a single point of failure in his China Dream. Whether the party of Xi can hold together without its linchpin leader is perhaps a question only time can answer.

Abridged extract from Party of One: The Rise of Xi Jinping and China’s Superpower Future, by Chun Han Wong, which is published on October 24 (Little, Brown, £25); order a copy at books.telegraph.co.uk

Illustrations by Justin Metz