Bayard Rustin’s connection to queer history may have started with his very name

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

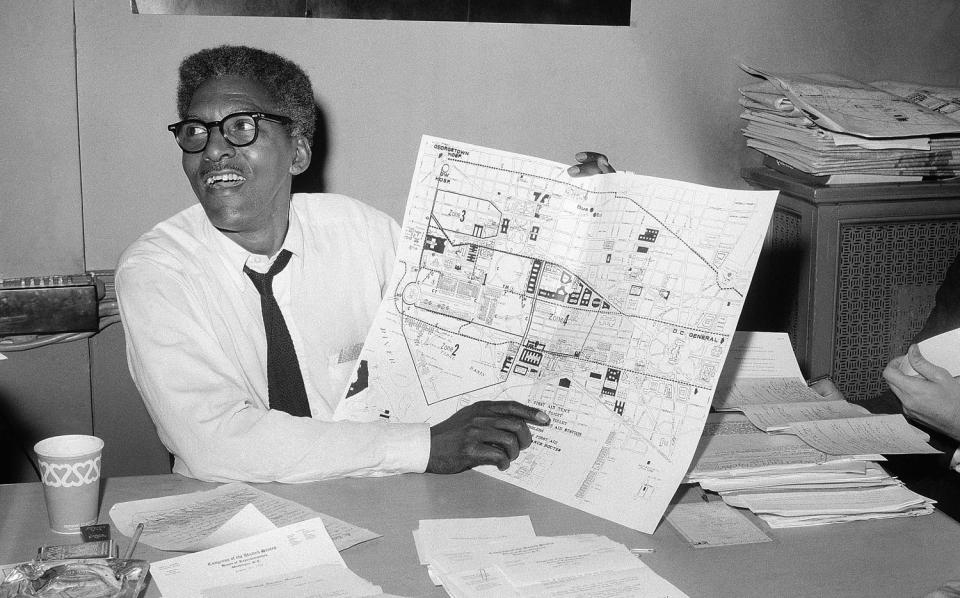

The movie “Rustin” has finally shone a proper spotlight on the life and crucial work of civil rights pioneer Bayard Rustin, picking up abundant accolades along the way that include an Oscar nomination for its lead actor, Colman Domingo.

Created for and embraced by wide audiences, Netflix’s “Rustin” biopic openly incorporates its title character’s sexuality, revealing how Rustin’s refusal to hide his gayness likely prevented him from taking a more prominent place — at least publicly — in the struggle for Black equality in America.

Rustin has also long been revered for his vital contributions to queer culture and history, first as an unapologetically out gay man within the greater civil rights movement, and later as a vocal advocate for LGBTQ rights in particular.

But Rustin’s connection to queer culture may have stretched back even further, indeed to the very beginning of his life. Born Bayard Taylor Rustin in West Chester, Pennsylvania, in 1912, he was named after Bayard Taylor, the man some now credit with having written America’s first gay novel some four decades earlier.

At the time of Rustin’s birth, Taylor was West Chester’s most famous son, thanks to his eminent career as a writer and diplomat. Likely just as importantly for Rustin’s grandmother Julia, who named him, Taylor had come from West Chester’s Quaker community, as had she.

Born in 1825, Taylor first rose to national fame as a poet and travel writer, publishing several books of poetry and travel essays in the 1840s and ‘50s. He published his first novel in 1863, followed by two more that same decade.

By 1876, Taylor’s prominence was so great that he was commissioned by Philadelphia’s Centennial Exhibition to write an official poem honoring America’s 100th birthday. The crowd of more than 4,000 people that gathered on July 4 to hear Taylor recite his “National Ode” gave him the largest-ever audience for a poetry reading, a record that would stand for the next 85 years.

A few years earlier, in 1870, Taylor had published his fourth novel, “Joseph and His Friend: A Story of Pennsylvania,” serialized chapters of which also appeared in The Atlantic Monthly. At the center of the book’s plot lay the extraordinarily close and undeniably homoerotic bond between two young men, Joseph Asten and Philip Held, who fatefully meet after eyeing each other up on a train ride through eastern Pennsylvania.

A few years older than the struggling-to-conform Joseph, and already made wiser by a stint on America’s western frontier, Philip “argues for the ‘rights’ of those ‘who cannot shape themselves according to the common-place pattern of society,’” wrote Robert K. Martin in the 2002 edition of the criticism anthology “The Gay and Lesbian Literary Heritage.”

In a pivotal scene from the novel, Philip takes Joseph’s hand, draws him nearer, flings his arms around him and holds him “to his heart.”

“O Philip, if we could make our lives wholly our own!” Joseph laments. “If we could find a spot—”

“I know such a spot!” Philip gushes back. “A great valley, bounded by a hundred miles of snowy peaks; lakes in its bed; enormous hillsides, dotted with groves of ilex and pine; orchards of orange and olive; a perfect climate, where it is bliss enough just to breathe, and freedom from the distorted laws of men, for none are near enough to enforce them! … I will go with you, and perhaps—perhaps—”

Long held as a prime example of late 18th century romantic male friendship in literature, in recent decades “Joseph and His Friend” has been reinterpreted by some LGBTQ writers and scholars as America’s first gay novel.

“Even post-Stonewall there was a hesitation to say ‘Joseph and His Friend’ was a homosexual novel, let alone America’s first,” observed author L.A. Fields in her 2017 book, ‘The Annotated Joseph and His Friend: The Story of America’s First Gay Novel.’ “But it is still the strongest candidate.”

Fields told NBC News that any earlier books with “glimmers of masculine fixation” were either not American, like James Hogg’s anonymously published “The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner” from Scotland in 1824, or not explicit enough to qualify as a gay novel, like 1799’s “Edgar Huntly, Or, Memoirs of a Sleepwalker” by Charles Brockden Brown.

The latter, like Taylor’s “Joseph and His Friend,” is set in rural Pennsylvania, but its obsessive male fixation revolves around the main character’s murdered friend — “not someone living whom he dreams of running away with and kisses, a startling scene which does take place in ‘Joseph,’” Fields said.

Like many scholars, Fields said she believes Taylor based “Joseph and His Friend” on the real-life relationship between early 19th century poet Fitz-Greene Halleck — sometimes called “the American Byron,” and whose statue graces the Literary Walk in New York’s Central Park — and his beloved friend Joseph Drake.

“For someone like Bayard Taylor who admired Halleck from a young age both personally and professionally as a writer, it seems like a very obvious inspiration, even if he never explicitly affirmatively declared it, as far as we know,” Fields explained. “Halleck’s relationship with Drake was the making of his life and literary career, and Drake’s loss, first to marriage and then to death, forever colored Halleck’s outlook.”

As for Taylor’s own sexuality, the evidence is somewhat murkier. He married twice and fathered a daughter, but he also maintained an unusually strong friendship with a German businessman named August Bufleb — whom he met on a train, perhaps foreshadowing the meeting between the characters of Joseph and Philip.

“Bufleb built him a special guest house on his property so that Taylor would visit him, and Taylor later married this man’s niece so they could be family,” Fields said.

“Joseph and His Friend,” the last of Taylor’s novels, was not particularly well received by critics of its day, though it’s unclear whether that owed more to its quality or its inclusion of a jarringly close male relationship.

“It is an unpleasant story of mean duplicity and painful mistakes,” wrote Taylor’s biographer, Albert H. Smyth, of the book in 1896. “The characters are shallow and their surroundings mean. There is not a single pleasing situation or incident.”

Plenty of readers must have disagreed, because by 1893, “Joseph and His Friend” had been reprinted eight times and translated into German. According to a widely shared newspaper account following Taylor’s death in 1878, the novel even became a main topic of discussion between Taylor and Germany’s Chancellor Otto von Bismarck when they were first introduced, with the German leader telling the author what he disliked about the book, and Taylor defending his literary choices.

When they met again by chance a few days later, von Bismarck was re-reading “Joseph and His Friend” and had already changed his mind about the story. “On the whole, I think you’re right about it,” he told Taylor.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com