By barge, rail or truck? Feds propose travel routes for Indian Point's nuclear fuel

At Indian Point nuclear power plant, 125 hardened casks of spent radioactive fuel sit idle, waiting until the federal government can figure out how to safely transport and dispose of them.

So far, no one's been able come up with a plan everyone can agree on, but hundreds of pages of documents offer clues on the range of options.

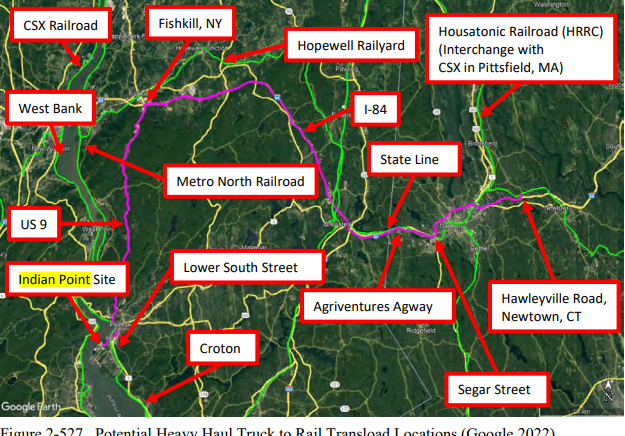

The radioactive waste stored at Indian Point could be trucked to Connecticut along U.S. 9, to Metro-North railyards in the lower Hudson Valley or by barge along the Hudson River, according to an Energy Department study of shuttered nuclear power plants.

The 558-page study released in February is based on site visits over the past 12 years at 18 power plants in 13 states, as well as one still in operation and a nuclear waste site, both in Illinois.

It offers up dozens of potential truck, rail and barge routes that could be used to alleviate the nuclear power industry’s biggest headache as it tries to capitalize on the nation’s push for carbon-free energy sources: What to do with spent fuel stranded at 75 sites across the U.S.A.

Nearly 90,000 metric tons of radioactive waste is being stored at the nation’s nuclear power plants at a cost to the federal government of more than $9 billion and counting. The total is expected to grow by 2,000 metric tons a year.

And there’s still no place to put it. A decades-old effort to build an underground repository in the Mojave Desert northwest of Las Vegas floundered in 2010 amid political opposition. Efforts to build interim sites in western states are mired in legal challenges spearheaded by the oil and gas industry.

Anti-nuclear groups say the answer is keeping it where it is — at shuttered and operating nuclear power plants in 33 states.

They say it’s too dangerous to move radioactive material across public highways, railroads and waterways.

“That DOE is relying even more so than ever, it seems, on barge shipping, is very concerning,” said Kevin Kamps, a radioactive waste specialist for the anti-nuclear group Beyond Nuclear. “I mean, look at what just happened in Baltimore. What if a high-level radioactive waste barge were involved in a major disaster like that?”

Beyond Nuclear is fighting efforts to build interim repositories for the waste in Texas and New Mexico, where it has found allies in oil and gas companies eager to keep drilling in the Permian Basin.

Radioactive fuel on trucks to Connecticut, lower Hudson Valley?

Several of the shuttered plants studied don’t have direct rail access, which means multiple modes of transportation would be needed, in some cases all three.

At Indian Point, the 125 casks of spent fuel housed at the site could be put on trucks and delivered to nearby rail links.

The report lists eight routes for heavy trucks, most of which would use U.S. 9 North. Four options include travel to rail links in the Connecticut towns of Newtown or Danbury.

Fuel: Nuclear waste stranded at Indian Point as feds search for permanent solution

The Hawleyville Road rail yard in Newtown, some 60 miles from Buchanan, has been used to receive truck shipments of low-level waste from Indian Point that have been sent by rail to a waste site in Andrews, Texas.

Other possible options include the Hopewell Railyard in Hopewell Junction, some 30 miles from Indian Point. It’s run by Metro-North Railroad but not connected to its commuter rail network.

Also included as possible rail links are Metro-North’s Croton-Harmon Railyard in Westchester County and Lower South Street in Peekskill.

All the routes would need to be approved by the U.S. Department of Transportation, which oversees the movement of spent fuel across the nation’s highways.

Decommissioning funds for sports teams? Indian Point owner Holtec used $63K in ratepayer funds for sports teams, fashion show

What about barges to move Indian Point's spent fuel?

Indian Point, some 35 north of New York City, sits on 240 acres along the Hudson in the village of Buchanan. It was once the site of an amusement park where day travelers would come by boat from New York City.

To use barges, the Indian Point site would need to fortify a dock at a cost between $2 million and $6 million, the study notes. The area was used to deliver a massive transformer to the site in 2016.

The Energy Department report included barges is an option at 17 of the 20 sites it visited. Many of the nation’s nuclear plants were built beside lakes, rivers and oceans, which are used to discharge hot water from reactors or in emergencies to cool down reactors.

This is not the first time barges have been broached as an option for Indian Point’s fuel.

In 2020, the plant’s owners, New Jersey-based Holtec, said it was considering using a portion of $2.3 billion in decommissioning trust funds to move spent fuel by barge. Indian Point is among 17 nuclear power plants across the country that don’t have rail access.

And a 2002 Energy Department study of possible routes to an underground site at Nevada’s Yucca Mountain Indian Point fuel could be moved by barge down the Hudson to railyards in New Jersey for the trip west.

The proposal ignited an outcry from lawmakers in both states.

Attempts to use the Hudson for radioactive transport would likely run into opposition.

Last year, responding to concerns raised by the environmental group Riverkeeper and others, Gov. Kathy Hochul signed into law a bill that would prohibit the discharge of millions of gallons of radiological into the Hudson.

Holtec said the decision will delay the completion of decommissioning until 2041, eight years longer than its earlier estimate.

Radioactive: Hochul inks Indian Point bill but radiological waste debate rages on

What options are best? What the nuclear industry says

Nuclear energy proponents, including the Nuclear Energy Institute, say some 1,300 shipments of spent have been moved across the country by barge, truck and rail in hardened containers without a release of radioactive material.

“Trucks are commonly used for smaller shipments,” said Rod McCullum, a specialist in nuclear waste transport at the NEI. “Rail for larger shipments. Fuel from the Navy’s nuclear-powered ships is routinely transferred from the ports in which the ships are refueled to inland storage facilities using both methods.”

Barges were used to move spent fuel from the Shoreham nuclear power plant on Long Island, the Limerick Plant in Pennsylvania and overseas in Sweden, France, Japan, and England.

For now, with no place for the spent fuel to go, the Energy Department study remains mostly academic.

And, if a repository is chosen, it could take years to come up with a transportation plan.

Teardown: Why Indian Point nuclear plant won't close until 2041

What about the cost?

Nevada lawmakers opposed to the Yucca Mountain site used the transportation issue argue it wasn’t just just a Nevada problem, but one shared by all communities where the waste would pass through.

And there are still cost issues that haven’t been resolved, according to Fred Dilger, the executive director of the Nevada Agency for Nuclear Projects, a state agency born out of opposition to Yucca Mountain.

“Although we are learning about the best way to move waste from the various sites, there is no clear idea about who will pay for needed infrastructure upgrades, how long it will take and when it will begin,” Dilger said. “Many nuclear power plant sites may need costly, time-consuming improvements to enable shipments to take place.”

A snarl in nuclear energy's potential comeback?

The debate comes at a time when the U.S. nuclear industry is on the cusp of what some have termed a nuclear renaissance.

Government officials in Michigan, California and elsewhere, faced with hard-to-achieve climate goals, are rethinking their views on nuclear power.

The Biden Administration says nuclear power should be a key piece of its strategy to rid the electric grid of carbon-spewing energy sources.

In Michigan, officials are considering restarting the shuttered Palisades Nuclear Power Plant. And in California, rolling blackouts caused state officials to pivot in 2022 and reconsider opening the state’s last nuclear plant, Diablo Canyon.

Dilger said he’s unpersuaded by those who say the future lies in advanced nuclear options like small modular reactors that don’t produce the same amounts of spent fuel as traditional reactors.

“The recent boosterism about advanced nuclear wishes away the problem of waste,” Dilger said. “We already have more spent nuclear fuel than can fit in Yucca Mountain. Ideally, we should already be looking for a second repository and haven’t got the first. Advanced nuclear will make even more.”

Towns caught in the middle

Caught in the middle are communities that are home to shuttered nuclear power plants.

They’re dealing with the loss of property tax revenue from revenue-producing power plants, as well as canisters of spent nuclear fuel that makes redevelopment problematic.

The town of Vernon, Vermont, chose to scrap its police force in 2015 after the Vermont Yankee plant shut down in 2014, putting a strain on its $2 million budget. Police services were taken over by county sheriffs.

Fiscal planning helped the town weather the worst of it and Vernon’s tax rate is around the average for the region, said Tim Arsenault, the town clerk.

“Unfortunately, the whole issue right now is not in my backyard,” said Arsenault. “Nobody seems to want to have a depository for spent fuel. So, while some people may not like it, it’s there until something changes.”

Funds: Indian Point owner Holtec used $63K in ratepayer funds for sports teams, fashion show

Vermont Yankee, unlike Indian Point, has direct access to rail, which would be used to transport its containers of spent fuel.

Power plants owners have been able to recoup billions of dollars from the federal government as compensation for the failure to find a repository. A 2021 Government Accountability Office report pegged the total at $9 billion but that’s expected to grow in the coming years.

State and federal officials have passed measures to help towns where plants shut down. But Buchanan Mayor Theresa Knickerbocker said it’s not enough.

“It is time for the federal government to resolve this,” she said. “There was an agreement that was made. The nuclear communities did not agree to become de-facto storage facilities.”

Knickerbocker questions why nuclear plant owners are able to recoup their costs while towns can’t.

“Holtec and others sue the DOE every few years to recoup their expenses,” she said. “Why isn't the host community compensated? Either find a home for the spent fuel or compensate the community until it is removed from the site.”

This article originally appeared on Rockland/Westchester Journal News: How to move Indian Point's nuclear fuel? Feds identify possible routes