Before The Banks there was The Bottoms, a murderous neighborhood with future superstars

The Cincinnati riverfront is now the jeweled crown of the Queen City. It’s the face we show visitors on postcards or on national television broadcasts.

The glistening skyline beset with picturesque stadiums, the beautiful green swath of Smale Riverfront Park, condos and restaurants. We call it The Banks. A modern interpretation of living on the river.

It wasn’t too long ago that the riverfront was a mostly barren embankment, parking lots and spartan warehouses with just the white-rimmed concrete bowl that was Riverfront Stadium. It didn’t look very livable.

But for most of Cincinnati’s history, people really did live close to the river.

Our History: What was it like to live in Cincinnati in the 1870s? Let's travel back in time

Before The Banks, there was The Bottoms

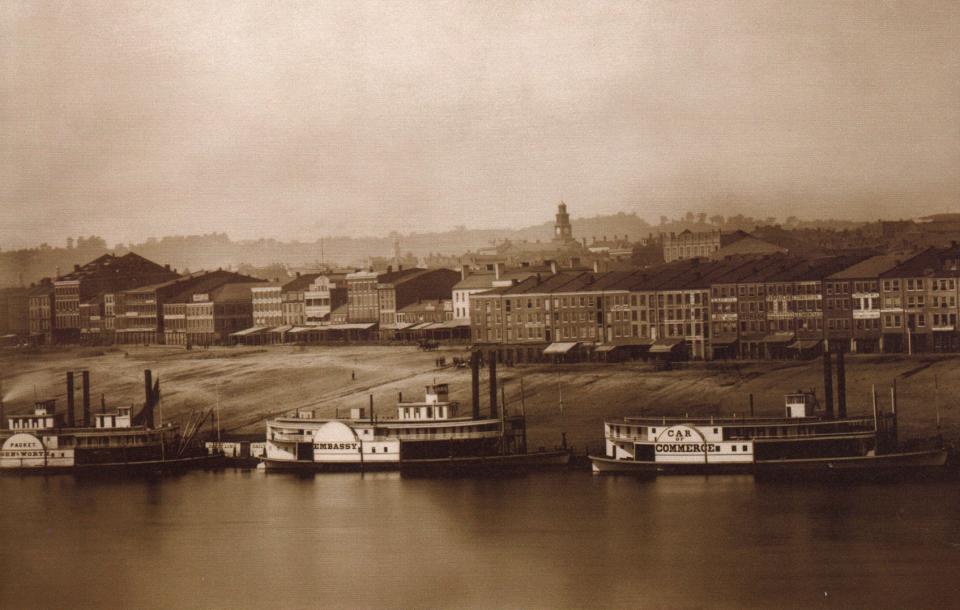

The riverfront has undergone a tremendous amount of change since the first settlers came ashore in 1788.

For Cincinnati’s first 50 years, life revolved around the activities of the river, so the people didn’t go far. Fort Washington, built for the defense of the Northwest Territory, was considered the farthest part of the settlement – at Third and Ludlow streets, about where Lytle Park is today.

As Cincinnati grew from a river town to a river city, the center shifted. By the 1840s, people had spread out to make their homes in Over-the-Rhine and suburban Mount Auburn. Fourth Street became the financial and commercial center.

The waterfront, meanwhile, still bustled with river traffic throughout the steamboat age. Those who mostly relied on the river − the merchants, dockworkers and immigrants − all found home nearby in a neighborhood known as The Bottoms.

The Bottoms spread from the Ohio River to Sixth Street, east of Walnut to the base of Mount Adams. It was a working-class neighborhood, where people lived, worked and worshipped.

As the poorer section of town, it was also where immigrants and the free Black population could find meager living accommodations. It was a true melting pot. Irish, German, Jewish and Italian immigrants, plus Chinese, Japanese and Lebanese, all crammed together in in their own clusters, with their own churches.

Christ Church on East Fourth Street and St. Francis Xavier Church on Sycamore Street are the only Bottoms-era houses of worship still around.

The Broadway Temple synagogue was at Sixth and Broadway before the congregation moved to Mound Street, and the building was sold to the Allen Temple African Methodist Episcopal Church. Wesley Chapel, First Presbyterian Church and St. Philomena – all are gone but demonstrate the diversity of the neighborhood.

Also formerly in The Bottoms: Pearl Street Market, the city’s first marketplace, established in 1816. Pennsylvania Station, on the Panhandle train route, at Pearl and Butler streets. B.H. Kroger’s first grocery store at 66 E. Pearl St.

Samuel Clemens, aka Mark Twain, worked briefly as a printer in Cincinnati in 1856 and slept at 76 Walnut St. Songwriter Stephen Foster worked for his brother’s steamboat agency and boarded on Fourth Street near Broadway in 1846, about when he penned “Oh! Susanna.” Leonard Slye, who would grow up to be Roy Rogers, “King of the Cowboys,” was born in a tenement building at 412 W. Second St. in 1911.

“When they built Riverfront Stadium, they bulldozed my birthplace,” Rogers once said. “I’m claiming second base as my birthplace.”

The rough-and-tumble Bottoms

Even in Cincinnati’s Queen City heyday, high society abutted next to squalor. Nicholas Longworth’s Belmont estate – today the Taft Museum of Art – was only blocks away from the seedier parts of The Bottoms along Front Street, now Mehring Way.

“For many years that section of Front Street between Broadway and Main, known as the Levee, drew a vigorous life from the steamboat trade at Public Landing,” according to “The WPA Guide to Cincinnati.”

“Front Street’s hotels and taverns played host to royalty and commoner, adventurer and banker, artist and soldier, roustabout and farmer, laborer and gambler.”

Boarding houses, taverns and bordellos accommodated the many stevedores, laborers and steamboat pilots. The rough-and-tumble section of The Bottoms – with unkind nicknames like Bucktown, Sausage Row and Rat Row – brought out thieves, prostitutes and criminals.

The one exception was the Spencer House, a fancy hotel at Front Street and Broadway that was a resort for Southerners who brought along their families and slaves in the summer. In 1866, President Andrew Johnson was greeted there with a lavish reception.

Lafcadio Hearn wrote about life on the Levee

Celebrated reporter Lafcadio Hearn wrote vividly of The Bottoms and its people for Cincinnati newspapers. A Greek-Irish immigrant married to a Black woman, he brought a unique sensitivity to his observations. His rich descriptions are the best there are of this long-gone period.

In a piece called “Levee Life” for the Cincinnati Commercial, published May 17, 1876, Hearn wrote:

“Along the river-banks on either side of the levee slope, where the brown water year after year climbs up to the ruined sidewalks, and pours into the warehouse cellars, and paints their grimy walls with streaks of water-weed green, may be studied a most curious and interesting phase of life – the life of a community within a community – a society of wanderers who have haunts but not homes, and who are only connected with the static society surrounding them by the common bond of State and municipal law. It is a very primitive kind of life. ..."

In an Aug. 22, 1875, article, “Pariah People,” Hearn wrote of Bucktown, a notorious district east of Broadway, between Sixth and Seventh streets, that he called a “haunt of crime,” where robbery and murder were nightly threats.

Hearn described the living conditions: “the congregation of dingy and dilapidated frames, hideous huts, and shapeless dwellings, often rotten with the moisture of a thousand petty inundations, or filthy with the dirt accumulated by vice-begotten laziness, and inhabited only by the poorest poor or the vilest of the vicious. …”

Bucktown was about all the Black citizens could afford. They shared the district with the poorer whites and vied for the same labor jobs, which led to frequent racial battles.

Things eventually got better.

Wendell P. Dabney wrote in “Cincinnati’s Colored Citizens” that by the time he came to town in 1894 “the mantle of civilization had almost completely overspread that unsavory section.” He credited two Black police officers who “cleaned up ‘Bucktown’ by sending most of its tough men and women to the hospital or workhouse. It still had many dissolute women and gambling men, but gradually murder became a lost art. …”

Riverfront redevelopment was decades in the making

“Slowly Bucktown disappeared,” the WPA guide reported. “One by one the shacks came down; sewers carried off the hellish odors; fills obliterated dirty scenes. Today large factories cover the site, and Bucktown is merely a livid memory.”

That was 1943. A few years earlier, in 1937, a terrible flood covered much of Cincinnati. The riverfront had always suffered frequent flooding, but this was something else. It caused the city of Cincinnati to reevaluate the riverfront problem.

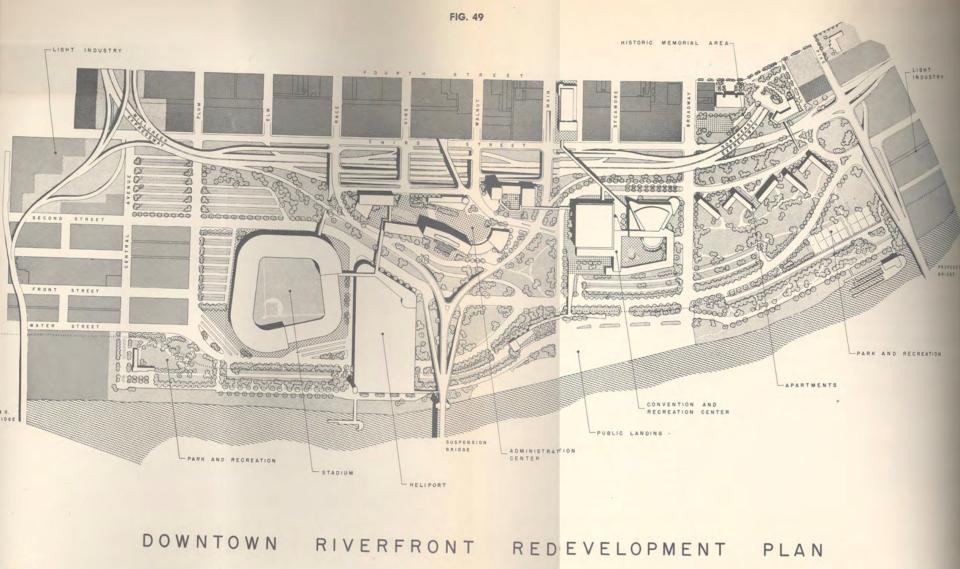

City leaders crafted the Metropolitan Master Plan of 1948, with designs to transform the riverfront into a vibrant showpiece of a modern city, with a baseball stadium, greenspace and a bypass expressway.

First came Fort Washington Way, which connected the west and east freeways across Downtown – and cleared a lot of the warehouses in the process.

Then came Riverfront Stadium in 1970, followed by Riverfront Coliseum in 1975.

Then nothing, really, for decades. The riverfront redevelopment project was excruciatingly slow in developing.

It took another couple of stadiums – Paul Brown Stadium in 2000 and Great American Ball Park in 2003 – to create bookends to a plan they were calling The Banks. The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in 2004 made the area more than just sports venues. Finally, Smale Riverfront Park in 2015 completed the riverfront redevelopment 67 years in the making.

Cincinnati finally got back to living on the river.

Take this quiz to test your knowledge of Cincinnati history

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Before The Banks, Cincinnati had The Bottoms, a murderous neighborhood