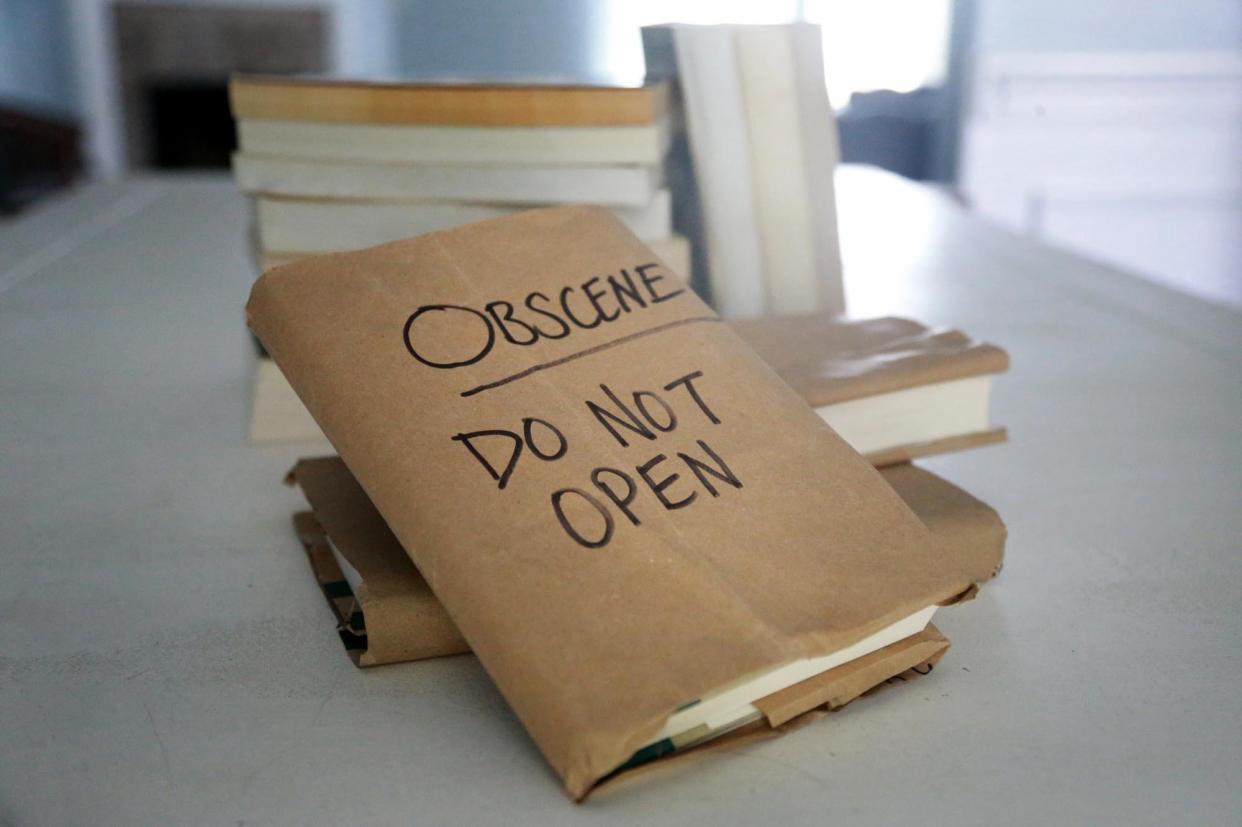

Ban those books? The debate over 'obscene' books in school libraries comes to Savannah

Beth Majeroni approached a desk bordered with a transparent, COVID-safe plastic barrier at the Jan. 5 Savannah-Chatham School Board meeting.

She spoke to the board members concisely and politely, with prepared remarks in hand, using her five minutes of allotted time to speak about books that are currently available to students in district libraries.

She offered up a warning before reading passages from Tiffany Jackson's "Monday's Not Coming" and George Johnson's "All Boys aren't Blue."

"Caution, extremely graphic language in both," Majeroni said.

She went on to read two descriptions of oral sex — one homosexual, one heterosexual, each about a paragraph long — spelling out the language used by the authors to describe genitals instead of saying the words outright.

In the "Monday's Not Coming" passage, the character is describing the act to another character. In the "All Boys aren't Blue" selection, the writing reflects the character's internal monologue during the act.

"I challenge all parents, school board members and school personnel to join me and others today, and unite to protect our children from pornography by purging our school libraries of inappropriate books," Majeroni said, looking up from her papers to make eye contact with the board. "If not you, then who?"

Ban those books?

This story is part of a series examining the debate over school library books being labeled "obscene" by activists across American, including a Savannah-based group that has challenged the presence of nine books in the Savannah-Chatham Public School System libraries.

Part 2: Parents of Savannah public school students can limit their access to library books

Part 3: Savannah-Chatham students take up mantle of defending 'obscene' books

Part 4: 9 Savannah school library books are called 'obscene'. Which books and how many students read them?

Majeroni has no children in the local school district. She's a board member and education chair for Ladies on the Right, a local conservative women's organization. She's also a former teacher, and has a master's degree in pharmacoeconomics.

"I thought, I'm the chair of education, I should get more up close and personal with what's going on in Savannah Chatham County schools," she said.

She leads a group that calls itself the School Board Action Team. Since January, they have been a mainstay at school board meetings, not missing a single one in that time.

The first issue they spoke on was the district's mask mandate last year. Then social-emotional learning, what she calls the "gateway to critical race theory."

Their efforts locally are a microcosm of a national trend: community activists, many of them professing to be conservatives, challenging facets of the public school system and pushing for more transparency from schools about what is being taught. High on their priority list is the removal of books they consider inappropriate.

In Texas, parents have swarmed to school board meetings to call for the removal of library books, most of which reference sexual identity, sexuality in general and race.

Conservative political candidates have seized on "obscene books" as a wedge issue. Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin's winning campaign last year propped up banning books and "parental control" as centerpiece issues.

Library books

The School Board Action Team has identified nine books that include sexual material in Savannah-Chatham public libraries. Physical copies of these books are in some, but not all, Savannah-Chatham school libraries, and some are also available through the district's online reading portal.

Some of these books have been in school libraries for years. Librarians select materials for their school media centers from using American Library Association (ALA) school library selection criteria and consider student needs and interests, which includes a call for materials to "be appropriate for the subject area and the age, emotional development, ability level, learning styles, and social, emotional, and intellectual development of the students for whom the materials are selected."

Once a book is in a school's collection, the district has a process in place for challenging these books.

But despite their regular attendance at school board meetings, the School Board Action Team hasn’t formally challenged any of the books. They haven't filed a materials consideration form — the first step in the local challenge process — for any of the books on their list.

They’ve just been reading these passages to the school board at meetings, sometimes wincing as they say the "bad words."

Majeroni says they haven’t filed any challenges because they were waiting to see what the General Assembly did during the session. And with good reason.

Read More: How misunderstanding of CRT, social emotional learning failed Savannah students, parents

New bill, no changes

The Georgia General Assembly passed a "Parents' Bill of Rights" - legislation championed by Gov. Brian Kemp - during this year’s legislative session.

Kemp sold the new law to legislators during his session-opening State of the State address in January, calling it a way to give parents better access to the materials taught to their children in schools as well as a way to “increase transparency in education by ensuring school districts have procedures in place for parental participation.”

But House Bill 1178 does little to change the process for parents hoping to challenge or access instructional materials in Savannah-Chatham schools. Most of the processes outlined in the bill were already in place prior to the passage of this piece of Kemp’s 2022 agenda.

And the bill came as a disappointment to Majeroni's group. They were hoping it would give them a better platform to challenge these library books, but the bill doesn’t do that.

The bill formalizes the process for accessing instructional materials, not those in the library, and gives an enforceable deadline. The first two weeks of each nine-week grading period are now considered the “review period,” and during this time, parents can request to view all instructional materials that will be used in their student’s classroom for the coming nine weeks.

State Rep. Josh Bonner (R-Fayetteville) was the author of the bill. He says the intention behind the bill rehashing these already-on-the-books provisions was to bring all of these laws into one place in the Georgia code.

Additionally, Bonner said, it brings the different policies of school boards around the state into uniformity.

“It may be duplicative, but it also brings it into one place. It's easy to find, and easy to follow, and get everybody on the same page, not only the parents, but also schools,” Bonner said.

However, another bill that passed this session, SB 226, takes direct aim at "harmful materials" and sets a Jan. 1, 2023 deadline for public schools to implement a materials complaint policy.

But SB 226 only applies to parents and permanent guardians of children in the school system, which excludes Majeroni's group.

And Savannah-Chatham schools already have a complaint policy in placeone that is strikingly similar to the bill's outlined process. The only difference would be a truncated 10-day timeline for an individual school to complete the review.

Other states

Georgia isn't the only state to pen a law aimed at school educational materials. Majeroni points towards Florida’s Parents’ Bill of Rights, House Bill 241, which does pull library books into the fold.

Florida’s law, enacted last summer, puts practically all media accessible by students under the umbrella: “materials used in the classroom, including workbooks and worksheets, handouts, software, applications, and any digital media made available to students."

The law goes even further by allowing parents to ”learn about the nature and purpose of clubs and activities offered at his or her minor child's school, including those that are extracurricular or part of the school curriculum.”

Majeronis says the Florida law is “the litmus test for a true Parental Bill of Rights, at least the best we've got so far.”

Last year, citing parents who “are rightfully outraged about highly inappropriate books,” Texas Republican Gov. Greg Abbott issued a directive asking various agencies to review school library book collections. A state representative also compiled a list of 850 titles, flagging them for potential removal from school libraries.

By April, more than 1,000 books had been banned in 86 school districts in 26 states, according to a CNN report.

The debate over whether books that some consider "obscene" has become a national, largely conservative platform. And while the School Board Action Team has yet to challenge any books in Savannah-Chatham school libraries formally, the district has policy guidelines for what books are allowed in libraries, and a formalized challenge process for those who want certain pieces removed. And at least one school has formed a Banned Book Club, with students stepping up to passionately defend these books, which they say are critically important — not just to them, but to future students as well.

But the fact remains: If a challenge to these books is to be raised, it will be raised through Savannah-Chatham's materials challenging process.

Will Peebles is the enterprise reporter for Savannah Morning News. He can be reached at wpeebles@gannett.com and @willpeeblessmn on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Savannah GA activists join fight to ban obscene books in public schools