‘The balloon might pop’: Fed’s corporate intervention spurs anxiety

The Federal Reserve, which long came under withering attack from President Donald Trump for not doing enough to boost the economy, is now drawing fire for a massive rescue of U.S. corporations that’s driving up Trump’s favorite barometer of success: the stock market.

The Fed’s months-long effort to support hundreds of companies hammered by the coronavirus crisis is also propping up weak firms and subsidizing large ones like Apple and Amazon that don’t need help. As a result, critics say, it’s inflating stock prices, widening wealth inequality, delaying a wave of inevitable defaults, and directing investment into poorly run corporations at the expense of the long-term vitality of the economy.

“The Fed is increasingly in a lose-lose situation,” said Mohamed El-Erian, chief economic adviser at Allianz, the parent company of asset management giant PIMCO. “If it doesn’t follow through, it will undermine its credibility and effectiveness. But if it follows through, it will be spending money to support many companies that certainly don’t need it.”

The Fed first announced it would move to calm the corporate bond market in March by pledging to take sweeping measures to bolster the securities, when economic shockwaves from the pandemic sparked a panic and raised fears of a full-blown credit crunch.

In a testament to the central bank’s credibility with the markets, its promises alone were enough to relax the nerves of many investors, allowing companies like Boeing and cruise line operator Carnival to borrow more cheaply from private lenders without needing to turn to the government.

Lawmakers from both parties praised the Fed for its quick action and moved to pass their own record taxpayer-funded rescue plan, including money to support the central bank’s efforts.

The Fed went further a couple of months later when, for the first time, it began directly purchasing debt of creditworthy companies on the open market, on top of indirect investments in other firms whose more risky bonds are rated below investment grade — or “junk.” That bolstered the psychological effect of its presence in the bond markets, which keeps interest rates low and whets investor appetite for still more corporate debt.

Those moves prompted even Trump, who repeatedly torched Fed Chair Jerome Powell for failing to turbocharge the economy before the pandemic struck, to say that the central bank chief has “really stepped up to the plate.”

Yet Sen. Pat Toomey (R-Pa.) at a hearing last month with Powell questioned why the Fed started buying bonds even though markets were functioning smoothly. Toomey, a free market proponent, argued that the central bank risks making it harder for investors to judge the relative strength of companies because bond rates are being kept lower across the board.

“I don’t see us wanting to run through the bond market like an elephant snuffing out price signals,” Powell responded.

Toomey, in an interview, said the Fed’s bond purchases are small enough “that it’s not truly disturbing,” though he remains unconvinced that they’re necessary. The Fed held roughly $9.4 billion in corporate bonds and exchange-traded funds as of June 30, a drop in a multitrillion-dollar market.

The Fed and its defenders say the central bank had to move quickly in the face of massive state-by-state lockdowns that threatened millions of jobs.

But the complaints about its approach long predate the pandemic: Toomey and others have warned for years that the central bank’s low-rate, easy money policies — which helped unemployment reach 50-year lows before the virus hit — have shielded investors from losses and pushed corporate debt to record-high levels.

There’s a danger of propping up so-called zombie companies — those that can only sustain their business operations by borrowing cheaply — through ultra-low long-term interest rates, said Toomey, who sits on the congressional commission overseeing the Fed’s emergency efforts.

The number of companies likely to have trouble making interest payments on their debt has been rising as a share of the corporate sector for the past decade, and is now close to a staggering 20 percent, according to data compiled by Deutsche Bank Securities.

There’s clear evidence that the Fed’s moves have staved off dire outcomes for some businesses. According to an analysis by Swiss bank UBS, markets in late March expected that corporations would default on up to 35 percent of debt rated as junk; that number had dropped to about 12 percent last week.

“The reality is they saved a lot of those firms,” said Matt Mish, the head of credit strategy at UBS.

There’s also an upside for otherwise healthy companies that were only in danger of failure because of the pandemic, given the specter of gargantuan job losses.

“What else could they do?” said William Spriggs, a professor of economics at Howard University and the AFL-CIO's chief economist.

“I get very upset with people on the left who yell at the Fed, and blame them — ‘Look! All they’re doing is pumping up the stock market.’ Uhm, so you want them to let all the companies go bankrupt? And then which jobs do you think will be left?”

Widespread corporate failures, moreover, would enrich a different type of investor: private-equity firms that specialize in restructuring troubled companies and are often criticized for loading them up with debt.

“It’s not obvious to me why we should shove more firms like Carnival closer to bankruptcy — and threaten to extinguish even more jobs than have already been destroyed — just to allow hedge fund vultures to reap the benefits of having their predatory loans be Carnival’s only option,” Josh Bivens of the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute wrote last month.

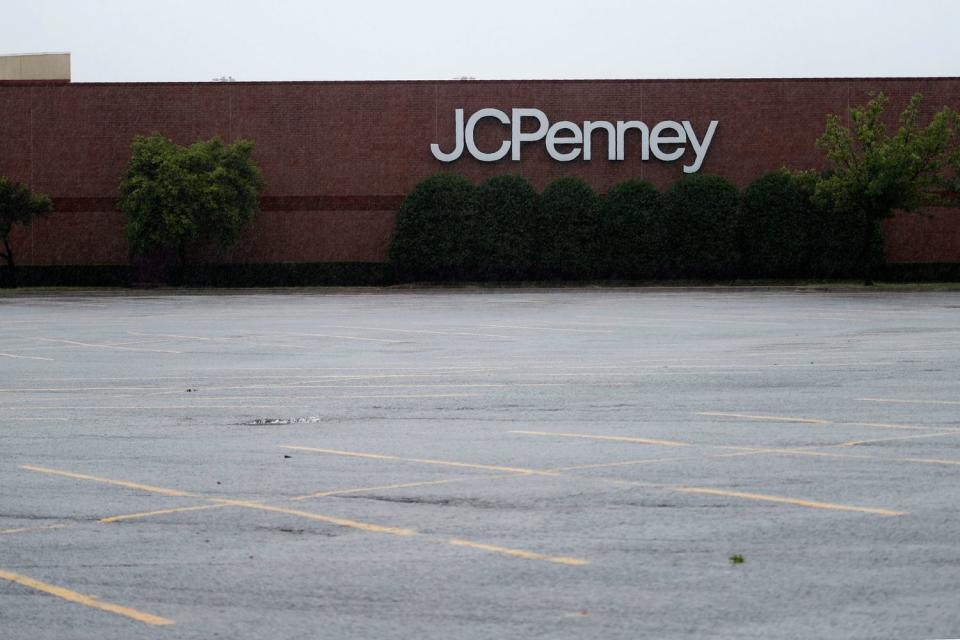

Many experts, however, fear a wave of bankruptcies will occur anyway, saying the Fed can only delay the inevitable if indebted companies aren’t bringing in enough revenue to pay back their loans. Already, some high-profile restructurings by JCPenney, Brooks Brothers, Sur La Table, and Hertz have demonstrated the limitation of the central bank’s intervention.

“As long as you can borrow money to make the minimum payment on the next card, you can keep that game going for a period of time, but it’s not sustainable,” said Thomas Salerno, a partner at the Stinson law firm who specializes in bankruptcy. “Eventually it’s going to collapse under its own weight.”

U.S. companies for now are taking a breath to see how the economy unfolds, borrowing just $70 billion through debt markets during the first week of July, according to a Financial Times report citing statistics from data provider Refinitiv. But that follows the largest fundraising blitz in history, with some $3.9 trillion raised globally by companies since March.

It’s not just the Fed’s help for struggling companies that has triggered a backlash. The central bank has begun buying bonds on the open market of every company that meets its eligibility requirements, which includes thriving businesses that wouldn’t have faced barriers to issuing debt — even when markets were most shaky. None of the firms specifically sought help.

“It was a framework that was meant to be as market neutral as possible,” said Julia Coronado, president of the economic consulting firm MacroPolicy Perspectives. “If they say, ‘we’re not going to buy Apple because they don’t need it,’ then they’re picking winners and losers.”

But Aaron Klein, a former Treasury Department official now at the Brookings Institution, said such bond purchases will increase inequality by further enriching only those with enough wealth to own stocks and bonds.

“The Fed’s response of buying corporate debt for well-capitalized, highly profitable companies is the wrong answer,” Klein said.

Tyler Gellasch, executive director of the investor advocacy group Healthy Markets Association, agreed: “It’s the equivalent of handing a billionaire another hundred bucks and saying, ‘I just want to make sure you’re okay.’”

In all, the Fed has pledged to buy the bonds of roughly 800 companies, but “most bonds have rallied whether the Fed has bought them or not,” UBS’s Mish said.

The Fed’s efforts have also proven a windfall for stocks. Amid a series of punishing selloffs in March, well-timed central bank announcements helped get markets moving again and many equities had regained most of their losses by early July. Savers seeking higher returns have also had few alternatives to stocks, with Treasury yields near historic lows.

According to S&P Global Market Intelligence, all 11 sectors of the S&P 500 index are expected to notch year-over-year declines in earnings for the second quarter. Yet the index has regained nearly all its losses since the market hit bottom in March.

That has brought into sharp relief the disconnect between share prices and the reality on the ground for working Americans.

On April 9, the Labor Department announced a record 6.6 million people had filed unemployment claims the previous week. But stocks shot up with the Fed announcing the same day that it would offer $2 trillion in additional lending for corporations as well as state and local governments.

The Fed might need to ramp up its bond-buying program if the economy weakens. But for now, New York Fed markets head Daleep Singh said the central bank has eased off.

“Fed purchases could slow further, potentially reaching very low levels or stopping entirely,” Singh said. “This would not be a signal that the [Fed’s] doors were closed but rather that markets are functioning well.”

But now that the Fed is in the corporate bond market, it will have to be delicate whenever it exits.

“We may not need the Fed to keep buying all that debt,” Gellasch said, “but a lot of folks are worried that if the Fed stops, the balloon might pop.”