Take me back to Saint-Germain, where I am most inspired and hopeful

Picture a musty men’s pub, sawdust carpeting the floor and hazy cigar smoke drifting aloft. It’s the mid 1940s in Kelso, the slow Scottish market town where the rivers Tweed and Teviot meet. Sitting with my great grandfather, single malt scotch in hand, is a doe-eyed, dark-haired Parisian in a powder pink Dior couture suit and matching veiled hat, technicolour against the blur of her neutral backdrop.

This woman, un-phased by her invasion of the masculine territory, was called Agnès Chabrier. She was a prolific French novelist, who would travel the world solo in the fifties. Destined to explore conflict, she was born the very day that WW1 erupted, on August 2, 1914.

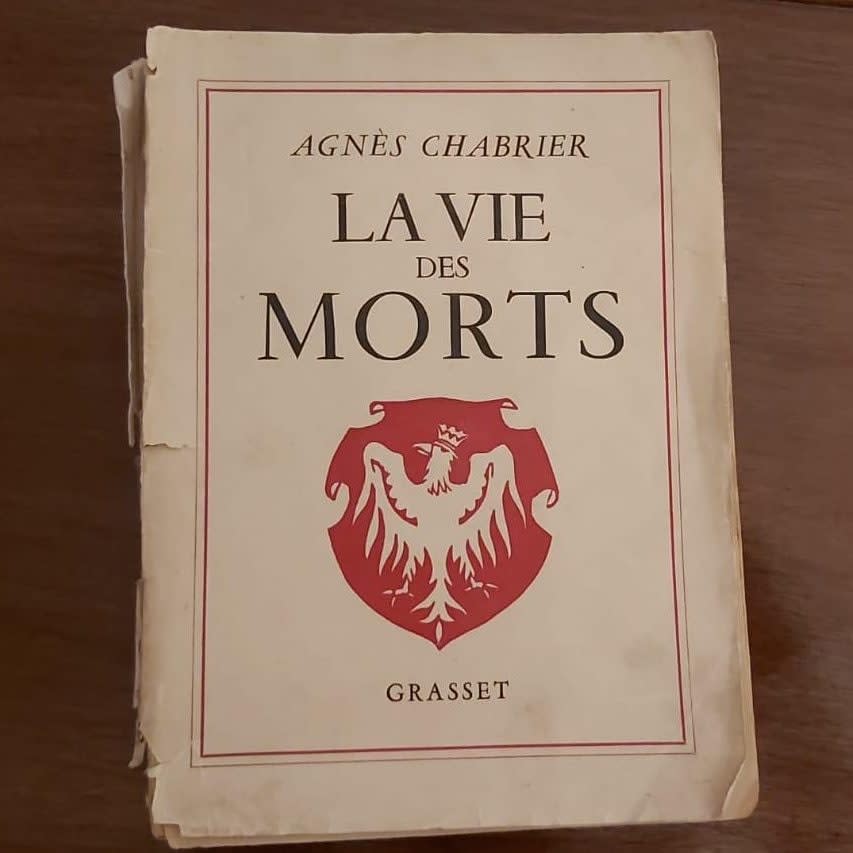

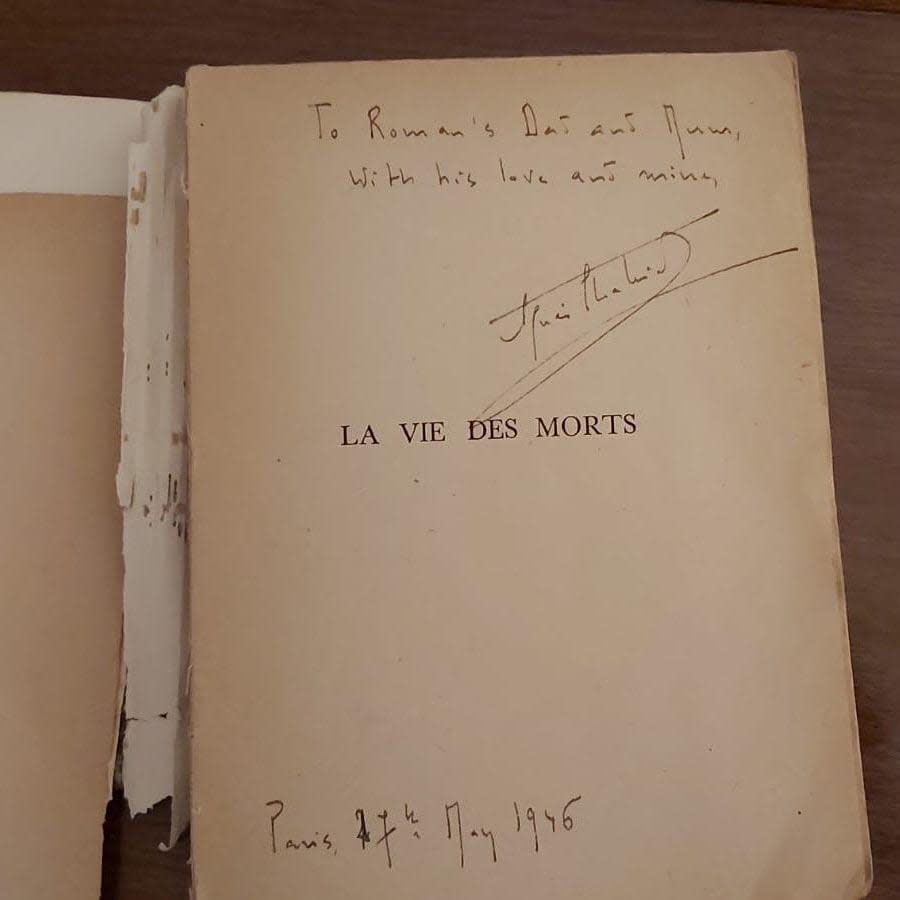

Agnès wrote controversial political books as well as ‘pot boilers’ under the pseudonym Daniel Gray. La Vie des Morts (1946) (The Life of the Dead), winner of Le Prix des Critiques, marked the beginning of her lifelong political attack on Germany and the USSR for their invasion and destruction of Poland, motherland of her late fiancée, Captain Roman Sikora. I have beside me an original copy, frail and disintegrating. Penned inside: 'To Roman’s Dad and Mum, with his love and mine, Agnès Chabrier. Paris, 27th May 1946'.

And here is where Agnès’ story ties into mine. Roman stayed with my great-grandparents in Kelso during WW2, after release from a Spanish prison camp. To him, they were Mum and Dad - such was their bond. After Roman died fighting for Falaise in 1944, Agnès arrived unannounced at my grandparents’ door to explore his beloved adopted home.

She insisted my great-grandfather take her to a local men’s pub. And, as with Agnès, he had no choice. “She fell in love with Scotland from the very start,” my grandmother, nicknamed Gagi, tells me, “and that’s why she came back and back and back.”

But Gagi was lucky – from the age of 14 she was allowed to spend summers in Paris with Agnès inside her vast apartment on Boulevard Raspail. WW2 had not long finished and she was the first pupil in her school to go abroad. At home in Edinburgh, 70 years later, she traces her finger over the plump scarlet cushion indicating a V. “That’s Boulevard St Germain and that’s Boulevard Raspail. Here they join, and Agnès lived…here. Right before they meet.”

Her stories from these summers are the very reason I committed to becoming a writer and learning French, later moving to live near Paris, hoping that I, too, might experience a similar magic. When I spend time in Paris, as I still try to once a year, I sidle down those same boulevards, pausing briefly by Café de Flore where mice scurry from seat leg to plant pot, and wonder if perhaps Agnès had befriended Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre. After all, they lived just one street apart. I am at my most inspired and hopeful in those moments, surrounded by the huge, cream buildings with their ornate black balconies, the tales of Agnès and her expansive world jogging through my mind.

My relationship with her is intriguing. She is real through my grandmother’s voice and the rough feel of her books. But we never lived at the same time (she died in 1981). Yet I know intimate details.

I know that Agnès’ mother rose at midnight for one medicinal glass of champagne, that their maid was Portuguese. And I know that the book La Jeune fille et le monstre (The Young Girl and the Monster), was inspired by a trip to Loch Ness with my great-grandmother. I know secrets from behind the heavy doors of her luxurious apartment, guarded by ‘that suspicious concierge’. She is the protagonist in the fairytale I’ve heard one thousand times over.

If Agnès wasn’t travelling the world then the world came to her. “She collected people,” says Gagi. “Once she met somebody, they were friends for life,” and so belong to me a collection of meaningful characters from my grandmother’s summers abroad as Agnès’ miniature sidekick:

The snooty French publishers at a Bastille Day street fête and the American midshipmen who rioted that same night in the hotel opposite; then the less rowdy Americans who brought her with them to the first class lounge in the airport, “drinking champagne - and I was only 15!”

There was the porcelain-skinned Chanel model who became her unlikely companion on a train ride; and the Japanese lady, wearing a kimono, who came to stay with Agnès in Paris to tell the world of the atrocities inflicted in Hiroshima.

“But the most suspicious was the Slavic man with the gun,” Gagi remarks, “Agnès’ parents were out, as was the maid. She didn’t want them present. She went to get the afternoon tea, so it was just he and I in the drawing room. And he took his pistol out and rested it on the mantelpiece. I didn’t know what was going on!” She exclaims, every time. “But he looked frightened and he checked through the peephole very carefully before leaving.”

And this is what Agnès said to Gagi, on that day when she discussed politics in hushed voices with the mysterious man that wasn’t supposed to be there. “The day that the Russians take Paris, I’ll be the first to hang from my balcony.”

One day soon I hope to pass beneath that balcony again, and cross over the Seine to the Tuileries gardens on a long, thoughtful walk. Especially in these times, it helps to think of Agnès, who invited a myriad of characters from all over the world into her home to share her platform and help spread word of their oppression.

Sign up for the Telegraph Luxury newsletter for your weekly dose of exquisite taste and expert opinion.