The Lookout

The LookoutThe ABCs of the Chicago teachers’ strike: New evaluation system looms large

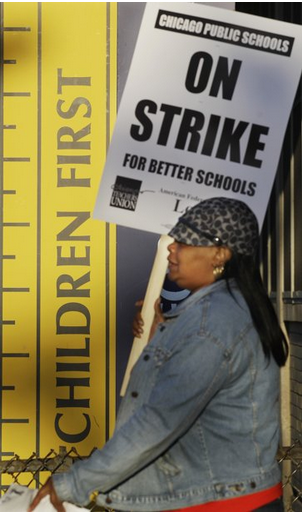

On Monday morning, 350,000 kids in Chicago found themselves without a classroom to bustle about as the city's teachers went on their first strike in 25 years. The sticking point? A new teacher evaluation system.

While Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel and the local teachers' union disagree on a long list of issues, including planned pay raises and sick day accrual, Emanuel said in a press conference Monday afternoon that the evaluation is the main obstacle to agreement. The new system would eventually use students' standardized test scores as 40 percent of a teacher's yearly evaluation. Teachers who don't improve their students' test scores would be fired.

Many Democrats, including Emanuel's former boss President Barack Obama, embrace this test-based way of judging educators. The president's "Race to the Top" federal program awarded money to states that agreed to rate teachers this way and institute other reforms, like encouraging the creation of more independent charter schools. As of last October, teachers can be dismissed in 14 states based on their students' test scores.

Union supporters argue that evaluating teachers using tests can be tricky, and that this "value-added" measurement can be volatile and inaccurate. Additionally, teachers who have a high proportion of poor students may have a harder time lifting their kids' scores than teachers who work in affluent districts. (About 80 percent of Chicago students qualify for free or reduced federal lunches.) As many as 6,000 teachers would wrongly lose their jobs under the system, says Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) President Karen Lewis. "Evaluate us on what we do, not the lives of our children we do not control," she said while announcing the strike, according to Reuters. But reformers counter that teachers should be responsible for helping their students score better on tests, and that current evaluation systems provide no way for ineffective teachers to be identified or removed from classrooms.

Emanuel doubled down on the new evaluation system Monday, as negotiations between CTU and the city dragged on. "What we can't do is roll back what's essential to improving our quality of education," Emanuel said at the press conference, flanked by children. He called the strike "totally unnecessary."

While other city and state leaders have pioneered test-based evaluations without prompting strikes, one sticking point that may make Emanuel's reforms more controversial is a lack of money. The school district is facing a $3 billion deficit over the next few years. Former Washington, D.C., Schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee was able to overhaul the city's teacher compensation and evaluation system in part by offering big pay increases for teachers who thrived under the new system. But Emanuel has no such leverage.

"The mayor is pushing for dramatic Obama-era teacher quality reforms, but doesn't have a lot of money to help the medicine go down," Rick Hess of the American Enterprise Institute told Yahoo News.

Union organizer and former social studies teacher Jackson Potter said one issue the teachers are striking over is poor facilities. Teachers are upset that some schools lack playgrounds or libraries, while others convened in "sweltering" August classrooms without the benefit of air conditioning. Meanwhile, the facilities budget for the city has been slashed. Emanuel dismissed this complaint on Monday, saying the teachers aren't actually striking over facilities. "It's 71 degrees outside," he said. "You don't go on strike for air conditioning."

But the issues leading to the strike have been building for quite a while, said Potter. When current Secretary of Education Arne Duncan ran Chicago's schools, he pioneered a new aggressive approach of closing down schools whose students performed poorly on tests. Duncan's strategy led some teachers, who felt they were being blamed for teaching in difficult, high-poverty schools, to form a more radical branch of the union, called Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators (CORE). The organization has been instrumental in the current strike, and similar groups have formed in other big cities with strong teacher unions, such as New York and Los Angeles, potentially setting the stage for more high-profile strikes in the future.

"I think we're likely to see other cities going down the same road as Chicago," Hess said.