Author Steacy Easton discusses new Tammy Wynette retrospective book

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The line between honesty as a brutal truth or marketing trope and the gauze of stylish kitsch laid over female artistic legacies in country music is troublesome. In author Steacy Easton's latest, University of Texas Press Music Matters series-released work, "Why Tammy Wynette Matters," they painstakingly interweave financial anxiety, maintaining the veneer of high femininity in Southern womanhood and other notions into Wynette's complex legacy.

Before a June 2 appearance at East Nashville's Novelette Booksellers from 7-8:30 p.m. CDT, Easton spoke to The Tennessean about lessons learned and perspectives raised by the book.

RSVP listing for Easton's appearance is available at https://www.novelettebooksellers.com/event-details/steacy-easton-why-tammy-wynette-matters-in-conversation-with-jewly-hight/form.

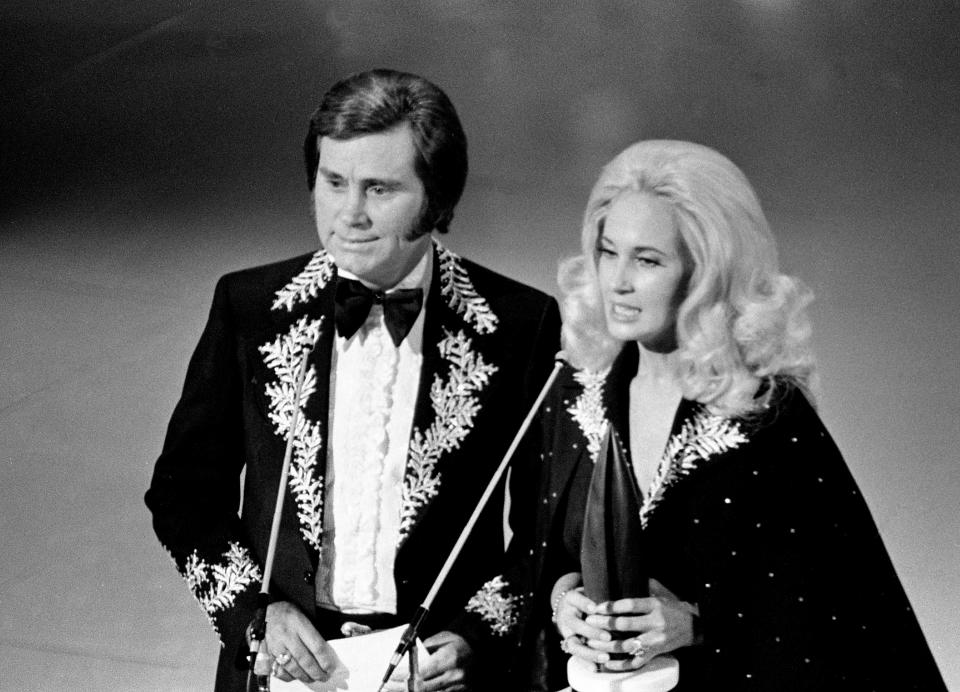

As much as she was an artist who maintained female stereotypes by desiring to "Stand By" George Jones and whisper "D-I-V-O-R-C-E" around children, she also brazenly achieved 20 No. 1 Billboard singles, plus advocated for rural and working-class women. Moreover, in her generation, she reduced male bias at country radio by developing into one of the genre's most dependably commercially successful artists.

Alongside enrapturing millions over her 33-year career with her mezzo-soprano voice, Wynette's most extraordinary ability was possibly allowing her art and reality to transpire in a provocatively messy interplay.

The line between art reflecting life and life embodying art was thin for Wynette, who Dolly Parton once joked that in the latter half of Wynette's life in particular, "[Tammy] still sang (her 1968-released hit) "Stand by Your Man" -- but never did."

Easton notes that Wynette was "trapped" by the enormity of the stage upon which her life's work and existence escalated.

Wynette was not country music's first female star to eclipse the sales of her male counterparts. However, she was the first to do so during the early days of the genre's countrypolitan crossover era. Thus, the added pressure of having to perpetually, in front of technicolor cameras on increasingly more mediums than ever, as an in-control conservative Southern belle who was also liberal, modern and wholly sexualized was perhaps too much.

Easton points out that Wynette's counterparts as stars like Jones -- her husband of six years and famed collaborator -- were more easily afforded the ability to embrace the totality of the wild and often confusing confluence of tropes then newly apparent in country music of the era.

"The strain of the mix of performative and real-time emotional vulnerability required to excel in that era -- especially in [Tammy's] performance on a song like [her 1966 debut cover of Bobby Austin and Johnny Paycheck's song] 'Apartment No. 9' -- just makes [parts of her catalog filled with some of] the saddest songs ever."

Even more bizarre is the idea that brilliant songs about divorce like "A Lovely Place To Cry" and "The Great Divide" highlight the era of Wynette's marriage to Jones while "Golden Ring" -- one of the all-time marriage songs -- was released while they were still on-stage partners after their divorce.

The notion of sentimentality as ersatz "bulls--t" is how Easton flatly defines the grand mirage of love presented by the iconic tandem. Loving sharing acclaim with someone more than liking their humanity is a fascinating notion to consider.

There have been enough tell-all books and documentaries from all eras of music about how every multi-person superstar act has engaged in a similar scenario. However, these were two people whose stardom, reality, families and children as much as homes and automobiles as shared, beloved assets -- were all hyper-celebrated in the public eye.

Solving for failing in the public eye was easy for Jones.

By 1980, he had somehow aged himself a generation and was a sunglasses-sporting, grandfatherly figure. Thus, his 18-week chart-topping solo single "He Stopped Loving Her Today" operates as not just a song about a man who vows to love his ex-partner until he dies in hopes that she returns -- which she does at his funeral.

The song's greatest strength may lie in the potential to read between the lines of its lyrics in a manner -- given that Jones had just appeared to be freshly healed from a bout with addiction and filing for bankruptcy -- where it can be assuming some manner of "Moses after seeing the burning bush"-level of white-haired outlaw religiosity in seemingly resurrecting his career by proclaiming his forever love for Tammy Wynette.

Again placing the burden on Wynette of having to meet a standard that she may not have entirely been able to embody, to Easton, spiraled the latter half of her life in a frustrating direction.

Wynette's ability to use her conservative sociopolitical leanings as a shield to guard her in times of fear -- or economic doubt -- troubled Easton in his research for the book. They describe a childhood of being raised in a "second-wave feminist" home where copies of Gloria Steinem-edited Ms. Magazine were on the coffee table as wildly polarized by comparison to how Wynette couched herself deep in the well of 70s and 80s era country music as an agitprop arm of conservative Southern political ideology.

"As much as she was unquestionably a victim, she also became politically tricky -- for me -- to support. Then, couple that with reading memoirs of her years after being with Jones and the idea that her other husbands did not support her career and livelihood [in a manner consistent with her time with George Jones]. It all just becomes a masochistic mess that never reconciles [itself]."

Post-Wynette, a continuing series of country's female stars -- from Wynonna Judd and Reba McEntire to Kelsea Ballerini and beyond -- have struggled with balancing modern-era country stardom's dichotomies and the frailties of reality converging upon the appearance of quaint, yet messy gentility that country music has always pre-supposed that its female stars were to portray.

Easton's grandest reveal presents a more profound question about how country music's history colors its future.

"Country's women and gender norms being met with mainstream popular culture caused deconstruction of women and gender in country music. That [deconstruction] has grown from laughable kitsch to a marketing scheme predicated on perspectives of historical memories."

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Author Steacy Easton discusses new Tammy Wynette retrospective book