Atlantic Killifish Highly Resistant To Toxic Pollution

There are frequent reports of how human activity is making life difficult for other species that co-inhabit Earth, but this one is about how at least one species is surviving despite the odds. Thanks to its extremely high level of genetic diversity, Atlantic killifish has evolved to withstand levels of toxic pollutants that would normally kill not just them but most other fish too.

Killifish (there are over 1,200 species of it, many of them very hardy, with some that can survive outside water for weeks) living in four East Coast estuaries were studied as part of research led by the University of California, Davis. And it was found the killifish were up to 8,000 times more resilient to the highly toxic industrial pollutants in the water bodies than other fish varieties.

Their genetic diversity, which is higher than any other vertebrate species measured, is what allows them to evolve faster than other creatures. But that is no indicator for us to think other creatures will follow suit and adapt the same way as killifish.

Andrew Whitehead, associate professor in the university’s department of environmental toxicology and lead author of the study, said in a statement: “Some people will see this as a positive and think, ‘Hey, species can evolve in response to what we’re doing to the environment!’ Unfortunately, most species we care about preserving probably can’t adapt to these rapid changes because they don’t have the high levels of genetic variation that allow them to evolve quickly.”

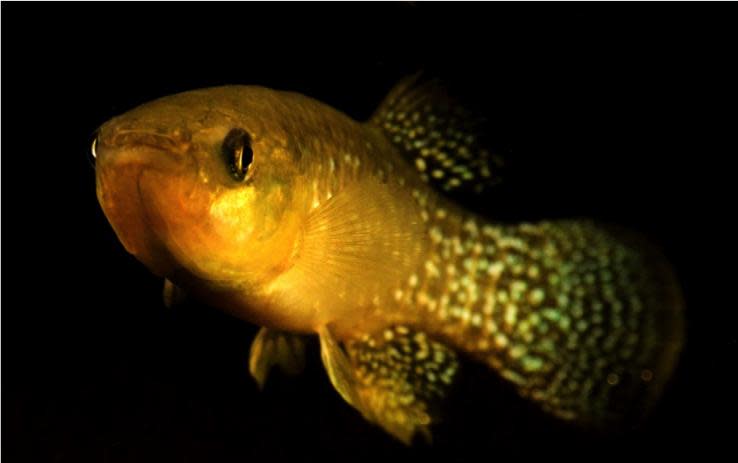

Atlantic killifish like this one have evolved to adapt to highly toxic levels of pollution. Photo: Andrew Whitehead/UC Davis

Looking at the genetic analyses of the nearly 400 Atlantic killifish, researchers surmised the fish already carried the genetic variation that allowed them to adapt to the toxicity, even before the sites they were collected from were polluted. That also suggests evolution may hold only very few solutions to dealing with pollution.

The study is important because it could help our understanding of how genetic differences in vertebrate species, including humans, affect sensitivity to chemicals in the environment, which in turn could be useful for designing ways to deal with pollution.

Titled “The genomic landscape of rapid repeated evolutionary adaptation to toxic pollution in wild fish,” it was published Friday in the journal Science.

Related Articles