Astronomers are out looking for the sun's long-lost siblings

The sun has siblings out there, and astronomers are looking for them.

Astronomers have surveyed and collected the "DNA" of more than 340,000 stars in the Milky Way, which will help them understand how galaxies formed and evolved over time.

SEE ALSO: Software used to study stars is helping protect the rarest and most endangered animals on Earth

Dubbed GALAH, the group of Australian and European researchers have been working on the project since 2013, and on Wednesday they publicly released data for the first time. By the end of the project, they anticipate to investigate more than a million stars.

Each star has its light analysed by the HERMES spectrograph, which is hitched on a 3.9 metre telescope at the Australian Astronomical Observatory (AAO).

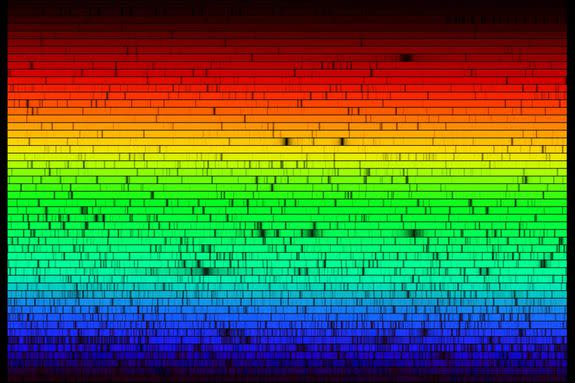

To figure out a star's "DNA," HERMES analyses the light to build a spectrum resembling a rainbow. Based on the length and locations of dark lines that appear in that spectrum, researchers can figure out the chemical composition.

"Each chemical element leaves a unique pattern of dark bands at specific wavelengths in these spectra, like fingerprints," Daniel Zucker, from Macquarie University and the AAO, explained in a statement online.

It takes about an hour to collect enough light from a star, but GALAH researchers can observe 360 stars at time with the help of fibre optics. Despite that, it took researchers 280 nights at the observatory since 2014 to collect enough data.

Image: N.A.Sharp, NOAO/NSO/Kitt Peak FTS/AURA/NSF

So how do researchers figure out if a star is related to the sun? Well, like the sun, each star was born in a massive cluster of thousands of stars.

Each of those stars will have the same "DNA," or chemical composition. The Milky Way has been pulling these stars apart, leaving them scattered across the galaxy.

"The GALAH team's aim is to make DNA matches between stars to find their long-lost sisters and brothers," Sarah Martell, from the University of New South Wales School of Physics, said in a statement.

While there are a number of ongoing large-scale archaeology studies of our galaxy, GALAH researchers are compiling a larger and more comprehensive data set as part of their survey.

"No other survey has been able to measure as many elements for as many stars as GALAH," Gayandhi De Silva, from the University of Sydney and the AAO, added.

"This data will enable such discoveries as the original star clusters of the Galaxy, including the Sun's birth cluster and solar siblings. There is no other dataset like this ever collected anywhere else in the world."

The GALAH announcement comes ahead of the massive release of data from Europe's Gaia spacecraft on Apr. 25, which is set to reveal the positions of 1.3 billion stars.

WATCH: A DIY dad made a Star Wars highchair for his son, and we're wondering if it comes in adult sizes