As Democratic race moves on from New Hampshire, black and Latino voters will have their say — maybe a decisive one

Congratulations, Democrats: The white phase of your presidential primary is over. Now comes the part where people of color finally get to vote — and how they vote could do more to determine the nominee than anything that happened in New Hampshire and Iowa.

After a split decision in the chaotic Hawkeye State caucuses, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders won Tuesday’s New Hampshire primary with roughly 26 percent of the vote, as long predicted. Former South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg, who ultimately inched past Sanders in the Iowa delegate count, placed second in the Granite State at roughly 24 percent — also as anticipated.

The next finisher was something of a surprise: Amy Klobuchar at roughly 20 percent. By beating expectations, the moderate Minnesota senator secured a ticket to the next round of caucuses and primaries.

Yet even Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who came in a disappointing fourth, with roughly 9 percent of the vote, insisted that she would continue her campaign. Likewise, former Vice President Joe Biden, who fell to fifth after his dismal fourth-place finish in Iowa, flew to South Carolina and vowed to persevere.

“It ain’t over, man,” Biden said. “We’re just getting started.”

As a result, Iowa and New Hampshire didn’t clarify anything. They didn’t even cull the top tier. They simply confirmed what we already knew. While Sanders is a plurality frontrunner who still hasn’t earned most Democrats’ support, the non-Sanders vote remains splintered among several niche candidates who have yet to build the kind of coalitions they need to elbow each other aside and overtake him — a problem that will only get worse once former New York Mayor Mike Bloomberg, who is patiently awaiting the field on Super Tuesday with rising poll numbers and $60 billion in the bank, finally begins to compete for votes.

Mainstream Democrats are clearly frustrated by this fractured state of affairs, which, left unresolved, could lead to the party’s first multi-ballot, contested convention since 1952. But the inconclusive outcomes in Iowa and New Hampshire could also prove to be poetic justice of sorts.

Why? Because neither state is even remotely representative of the broader Democratic electorate.

Nationwide, 2020 Democratic primary voters are expected to be 57 percent white, 20 percent black and 15 percent Latino, according to the latest CNN/SSRS poll. In Iowa, caucus-goers were 91 percent white, 3 percent black and 4 percent Latino. New Hampshire voters looked pretty much the same: 90 percent white, 6 percent black and only 2 percent Latino.

Yet these demographics are about to change dramatically, first in Nevada on Feb. 22, and then in South Carolina on Feb. 29. Four years ago, a far more representative 59 percent of Nevada Democratic caucus-goers were white; 19 percent were Latino, 13 percent were black and 4 percent were Asian. The same year, a full 61 percent of the South Carolina primary voters were black; only 35 percent were white.

Then comes Super Tuesday on March 3, with big delegate prizes in California (25 percent Latino), Texas (32 percent Latino, 19 percent black), Virginia (26 percent black), North Carolina (32 percent black), Tennessee (32 percent black), Alabama (54 percent black) and Arkansas (27 percent black).

In other words, voters of color now have a chance to winnow the field — and perhaps even pick the Democratic nominee.

So who will they elevate, and who will they eliminate?

Buttigieg, the 38-year-old gay former mayor of Indiana’s fourth-largest city, is perhaps the leading candidate for elimination. Despite an impressive run in all-white Iowa and New Hampshire — never before has such a young candidate with such an atypical background won a primary or a caucus — Buttigieg has struggled mightily to show he can attract black voters. He has failed again and again.

Over the last year, the Hoosier has surged three separate times in the national polls. Yet the same surveys have consistently showed that black voters are just not that into him. Buttigieg’s typical vote share in polls of black Democrats in South Carolina? Zero percent. He’s not performing much better with Latino voters in Nevada.

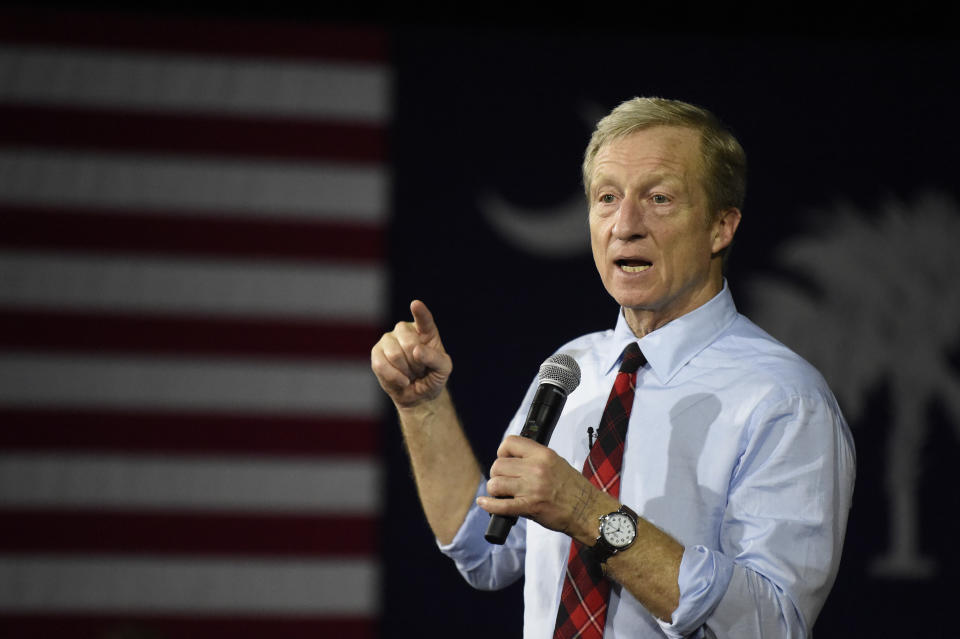

Buttigieg’s team believes that voters of color will give him another chance after his strong showing in Iowa and New Hampshire, but his history of racial controversies, both in South Bend and on the campaign trail, may have already rendered the former mayor a nonstarter, and the rise of Klobuchar, Bloomberg and even Tom Steyer (more on that later) will make it increasingly difficult for Buttigieg to achieve escape velocity in diverse states where he has long polled in the single digits.

Klobuchar has a similar problem going forward: Her national support among black voters stands at zero percent, and she has barely registered in past Nevada polls. Her post-New Hampshire momentum may get her a second look, but along with that will come increased scrutiny of her record as a tough-on-crime Minnesota prosecutor who nonetheless failed to prosecute a single killing by police and who may have put an innocent 16-year-old boy in jail for life. Buttigieg, Biden and even Warren are also much better organized than Klobuchar in the upcoming states. She has a lot of catching up to do — and she’ll have to do it in places that don’t play to her demographic strength among older and more centrist voters.

Biden could also suffer in the next round, but for the opposite reason. For the last year, he has led the polls in South Carolina, Nevada and key Super Tuesday states because of his familiarity and support among black and Latino voters. But it’s unclear whether that loyalty — and the perception of electability that underlies it — can withstand two or three dismal finishes in a row. After Iowa, the share of likely Democratic primary voters nationwide who told Quinnipiac that Biden has the best chance of beating President Trump fell 17 percentage points. Black voters (40 percent) said they still considered Biden the safest bet. But that was before he finished fifth Tuesday night.

“If Biden is coming in third or fourth in New Hampshire, the African-American community is going to look at [him] just like any other voter … and say, ‘I’m not sure that’s a good investment,’” Democratic pollster Cornell Belcher told the Atlantic before the primary.

Which brings us to the candidates who may have more to look forward to and less to fear as the campaign moves onto more diverse terrain.

Both of the billionaires, Bloomberg and Steyer, appear to be gaining ground with voters of color. As Bloomberg blitzes the Super Tuesday map with more than $300 million of ads — and as confusion seems to reign in the early-voting states — he has been ascending in the polls. According to the latest national Quinnipiac survey, for instance, the former New York mayor shot up 7 percentage points after Iowa to third overall, just 2 points behind Biden, who dropped 7 points.

A massive shift among black voters was the major reason why (despite Bloomberg’s controversial history with stop-and-frisk policing). The previous Quinnipiac poll, taken in late January, showed Biden commanding 49 percent of the black vote to Bloomberg’s 7 percent. The new Quinnipiac poll shows Biden at 27 percent and Bloomberg in second place at 22 percent, ahead of Sanders (19 percent).

Steyer is a similar story. In South Carolina, the California billionaire has spent $14 million on TV and radio ads and more than $100,000 on ads in black-owned newspapers, while hiring 93 staffers and assembling the largest operation of any campaign. He has been rewarded with double-digit poll numbers as a result. Likewise, in Nevada, Steyer has spent more than $10.4 million on advertising, dwarfing the rest of the field by a huge margin. This has helped him climb from fifth place in two November polls to tied for third- and fourth-place in two January polls.

This doesn’t mean Steyer will win South Carolina or Nevada, or that Bloomberg will sweep on Super Tuesday. But the better the billionaires perform — particularly among the voters of color who will play a pivotal role in the coming weeks — the harder they will make it for Biden or Warren to mount a comeback or for Buttigieg or Klobuchar to prove they can connect.

Sanders stands to benefit. He has already won the most votes in Iowa. He also won the most votes in New Hampshire, and the most delegates. He is not doing poorly in South Carolina; the polls there put him in second place, on average, and that was before Tuesday’s win. He has long led nationally among young black voters, and post-Iowa polls show him gaining 10 points among black voters overall and besting his rivals among nonwhite voters in general. Sanders also boasts the strongest Latino ground game in the field; though the sample sizes were minuscule, he won Latinos by 24 points in New Hampshire and nonwhite voters by 28 points in Iowa. Relatedly, the polling averages already show the Vermont senator leading by more than 5 points in Nevada and by more than 10 points in California.

Then again, the powerful Nevada Culinary Union sent out a flier Tuesday night warning its members, who are mostly nonwhite, that Sanders would “end” their health care by enacting Medicare for All — the latest twist in a race that’s only just beginning.

Regardless, the rest of the field is going to have to act quickly if they want to stop Sanders. And they’re going to need to get voters of color on their side.

—

Cover thumbnail photo: Sen. Bernie Sanders and Pete Buttigieg. (Photo illustration: Yahoo News; photos: Win McNamee/Getty Images, Matthew Cavanaugh/Getty Images)

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: