Art or evidence? Closest U.S. Supreme Court has looked at rap lyrics is for ‘true threat’

The closest the U.S. Supreme Court has come to assessing whether rap lyrics can be used in prosecutions was in a case where it looked at whether they were a “true threat” that made someone believe they would be seriously harmed.

In 2014, the nation’s highest court heard the case of Anthony Elonis, marking the first time the justices reviewed a true threats case involving lyrics.

Elonis had been found guilty of posting on Facebook rap lyrics containing violent language and imagery concerning his ex-wife, coworkers and law enforcement. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed Elonis’ conviction and ruled that prosecutors must prove that a defendant intended to carry out alleged threats.

Another Supreme Court decision from June of this year will likely influence how these types of cases are handled in the future, said Clay Calvert, a professor of law and the former director of the Marion B. Brechner First Amendment Project at the University of Florida. The court took up the case of Billy Raymond Counterman, a Colorado man who appealed a more than four-year sentence for stalking a local singer-songwriter and flooding her with messages on Facebook.

Music is protected First Amendment speech as long as it’s not obscene, defamatory or a threat, Calvert said. But experts, advocates and some legislators are concerned that the use of rap lyrics in criminal prosecutions violates the right to free speech — an issue the Supreme Court has yet to clarify.

How does artistic expression, a protected form of speech, make it to courtrooms?

Can lyrics be a crime?

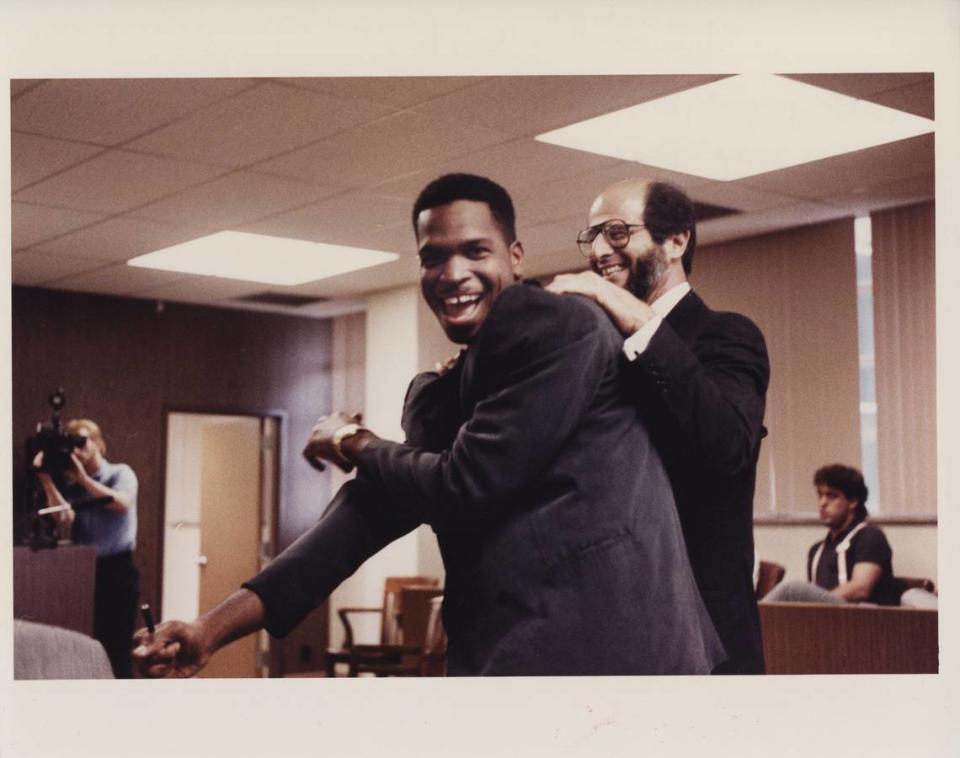

For rap legend Uncle Luke, the leader of the Miami-based 2 Live Crew, rap lyrics have long been weaponized to go after artists.

In 1990, 2 Live Crew’s raunchy music was at the center of a legal battle that tested the bounds of free speech.

Jurors had to decide if the group’s “vulgar and disgusting” lyrics, including platinum album “As Nasty As They Wanna Be,” known for smash hit “Me So Horny,” were obscene. The artists were facing jail time because their lyrics were considered a crime. The jury acquitted them.

“I’m like a proud father of hip-hop that’s not getting any credit, but I’m proud of fighting that fight,” Luke said. “If I don’t do that, if I don’t take on that fight, then we probably won’t be here right now and a lot of artists would be getting just straight locked up for lyrics.”

The way rap lyrics are approached when considered a crime differs from the 2 Live Crew era. Now, they’re being used in prosecutions to show that someone believed they would be harmed and so were true threats, which aren’t protected by the First Amendment.

The U.S. Supreme Court has heard true threat cases not involving lyrics over the years, but the only guidance offered on the use of lyrics is in the Elonis and Counterman cases.

In the Counterman case, the court ruled that prosecutors must prove that the defendant understood that the statements were threatening but made them anyway. Counterman’s stalking conviction was thrown out after a 7-2 decision.

“What the Supreme Court has made clear is that it’s not just how would a reasonable person interpret the lyrics,” Calvert said. “But you also have to look at now ... did the speaker consciously disregard a high risk that they would be understood as threats?”

Can race play a role?

Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, in a written opinion in the Counterman case, delved into the dangers of equating violent lyrics to threats — even if a threat wasn’t intended. She reflected on how that could lead to the overcriminalization of minority communities.

According to the Rap on Trial project, only about 2% of documented cases in which rap lyrics are mentioned involve white defendants. The bulk of those concern lyrics as threats.

“Members of certain groups, including religious and cultural minorities, can also use language that is more susceptible to being misinterpreted by outsiders,” Sotomayor wrote. “And unfortunately yet predictably, racial and cultural stereotypes can also influence whether speech is perceived as dangerous.”

While Elonis’ conviction was overturned, others haven’t been. Jamal Knox and Rashee Beasley, who recorded a rap song titled “F--k the Police,” were charged with terroristic threats and witness intimidation after name-dropping two officers involved in a 2012 scuffle.

Knox, who goes by the stage name Mayhem Mal, argued that the lyrics were protected by the First Amendment and that a conviction would violate his constitutional rights. A Pennsylvania court rejected the First Amendment claim and upheld his guilty verdict. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case.

Pointing to the experience of Knox and Beasley, who are Black, researcher Austin Vining argued that rap is viewed as a proxy for Blackness in the courts — and that prosecuting lyrics unconstitutionally restricts free speech rights. Vining was formerly a fellow at the University of Florida’s Marion B. Brechner First Amendment Project.

“Rap and hip-hop lyrics are not afforded the same First Amendment protection as other genres ... because of their strong association with Black culture,” he said.

Ending rap on trial?

As the practice is debated in courts across the country, several states have started taking legislative action to challenge the use of lyrics.

▪ California became the first state to restrict the use of rap lyrics in court when Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the Decriminalizing Artistic Expression Act in 2022.

CA is the 1st state to ensure creative content - like lyrics & music videos - can't be used against artists in court without judicial review.

Thanks, @JonesSawyerAD59 for your work & @yg @KillerMike @tydollasign @Tyga @MeekMill @E40 @TooShort for your dedication to the cause. pic.twitter.com/cpOSCiHh0X— Office of the Governor of California (@CAgovernor) September 30, 2022

▪ Louisiana’s Gov. John Bel Edwards signed the Restoring Artistic Protection Act in June. The law bars prosecutors from using lyrics as character evidence in trials.

▪ New York, in May, passed a bill in the state Senate that could limit the use of rap lyrics. It is not yet law.

▪ New Jersey’s Supreme Court ruled unanimously in 2014 that rap lyrics can’t be used as evidence in a criminal trial. At the center of the decision was the case of Vonte Skinner, an aspiring rapper who was convicted of attempted murder after lyrics written years prior were used against him. In 2022, state legislators tried to codify the ban.

▪ Illinois, Missouri and Maryland also introduced bills that would restrict the use of lyrics in courtrooms, but those haven’t been passed.

▪ Georgia’s U.S. Rep. Hank Johnson, a Democrat, introduced the federal Restoring Artistic Protection Act, known as the RAP Act. Johnson vowed to reintroduce the RAP Act, as long as he’s in office.

He spoke about the initiative at Rolling Loud in July.

“This is a criminal justice issue,” he said. “It’s also a First Amendment issue. [The legislation] protects freedom in this country. And the fact of the matter is that the freedom of rap artists is under attack.”