Arizona senior living center where resident killed roommate has had nearly 150 citations since

A Mesa assisted living center continued to make mistakes that endangered residents even after a woman with dementia killed her roommate, racking up more citations than any other facility in Arizona — by a lot.

Heritage Village received 148 state citations over the past three years. That's 2.5 times more than any other assisted living center licensed to serve residents who need the most help and supervision. Most others in Arizona had no more than a couple of dozen citations and about 40 facilities had none, according to an analysis by The Arizona Republic.

Heritage Village has also paid more fines than most; its penalties over three years added up to $18,500. Other facilities typically paid less than $2,000.

And that’s just for problems state investigators confirmed at Heritage Village. Arizona law doesn't require centers to report many resident injuries to the Arizona Department of Health Services — including one instance when a resident there hurt three others over two days, at one point forcing employees to hide from him in a locked bathroom.

“If someone is driving poorly, eventually the state takes their license away,” said Dana Kennedy, Arizona state director for AARP. “If a facility is being cited over and over again, then their license should be threatened.”

The state has not threatened to pull Heritage Village's license. Its investigators have not substantiated some complaints, including in a case documented by police where a detective told a grieving woman it appeared "the entire staff/system at Heritage Village facility failed" after her mom died and another where the detective concluded a resident had "substandard" care.

The Department of Health Services did not make any officials available for an interview for this article despite weeks of requests. The department's spokesperson noted in an email that it does not have jurisdiction to investigate and substantiate abuse, neglect or exploitation allegations, and that is Adult Protective Services or law enforcement's job.

Assisted living regulations give the department authority to cite facilities if managers fail to ensure that residents are treated with dignity and "are not subjected to" abuse, neglect and exploitation.

But a department official said in an email they rely on law enforcement or Adult Protective Services to decide whether abuse, neglect and exploitation happened. That is problematic: An audit this month slammed Adult Protective Services for substantiating less than 1% of all the cases it investigates while the national substantiation rate is 33%.

Even the agency's employees cited concerns with the quality of their investigations, according to the report.

The Governor's Office also did not respond to repeated requests for an interview about what Gov. Katie Hobbs plans to do to address shortcomings in Arizona's senior care system.

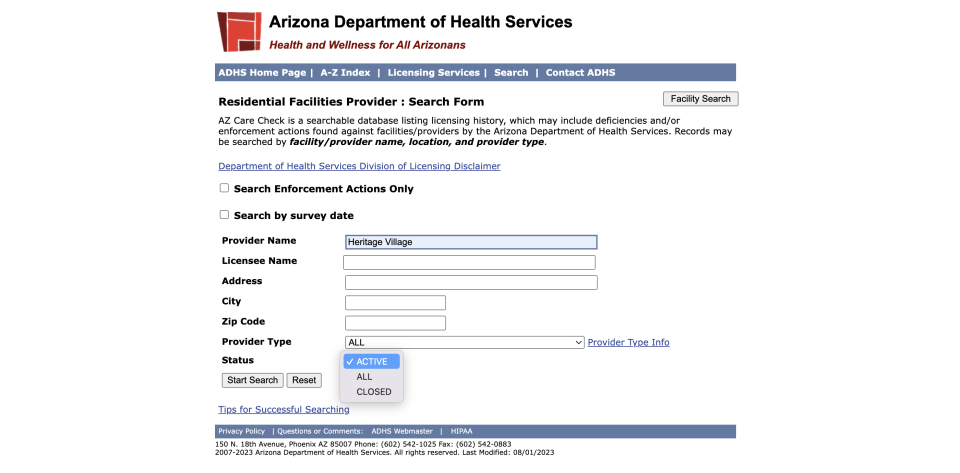

While state regulators handed out citations and fines, they didn't make it easy for people to find out about them. Because of how the state's record system is set up, most of Heritage Village's missteps are stored outside of obvious search results on one of the few public resources for consumers researching assisted living options.

The state-run website shows just one citation in a simple search of the facility's name.

The director of Madison Realty Companies, which operates the facility, said his team has transformed Heritage Village over the past year. The firm fired the previous management company, reinstated defunct physical therapy services, launched an on-site medical office, hired dozens more employees and provided better training, he said.

“Our goal is to provide good care to everybody,” said Gary Langendoen, managing director of Madison Realty Companies. “If anybody was injured in any way, that’s certainly not a good thing. We would try to do anything we could to correct that in the future. I would apologize to anybody if there was an injury.”

The facility’s record is cleaner this year compared with the recent past, with only eight rule violations. But Langendoen’s company acquired Heritage Village in 2017.

Langendoen said he had only a high-level understanding of what was happening at the facility until recently because a different company managed day-to-day operations.

Asked if he felt his firm stepped in at the appropriate time, he said, "I’m glad we’re operating it now."

The repeated troubles at Heritage Village are emblematic of failures within Arizona’s senior care industry that persist as regulators issue paltry penalties, if any at all, for breaking rules designed to keep vulnerable seniors safe.

The Arizona Republic created a computer program to capture the state's repository of facility inspections. Reporters then analyzed hundreds of enforcement actions and more than 3,500 citations, reviewed complaint data, police reports and body camera footage and interviewed families and former employees to produce this report.

Heritage Village looks nice from the outside. Family members whose loved ones have gotten hurt there said they were wooed by the greenery, the casitas with stone accent walls that offer a home-like environment and — upon first meeting — the cheerful employees.

But it didn't take long for them to believe it was all a façade.

‘I think they hired people that just didn’t care’

When Estalyn Bouchard's daughter came to visit her mom at Heritage Village soon after she moved into the facility in summer 2021, employees there didn't know where the 86-year-old was.

Maybe she left for Catholic services, they suggested. Estalyn was not Catholic. Her daughter, Dellene Bouchard, searched the halls and found her mom standing in someone else’s bedroom, with no clue where she was.

That signaled the beginning of a long, painful year.

Her kids bought her a chair and a nightstand. Those went missing. Her dentures went missing. Her walker went missing — twice. Her shoes went missing. Her socks, even with her name written on them, went missing.

At one point, her bathroom faucet was broken and she had no way to wash her hands.

Estalyn lost 12 pounds in a month when Heritage Village went on a COVID-19-related lockdown.

Because of her Alzheimer's, she needed help feeding herself, but she didn't appear to get that. Her daughter arrived one day to find her mom picking at a bowl of rice with her fingertips.

Her kids made a point to visit during mealtime to feed her.

"We were basically having to do their job for them," said another daughter, Carlyn Bouchard.

Carlyn found her wearing wet socks and stained clothes, her fingernails and toenails long and caked with dirt.

She documented many of the issues in emails she sent to management and Estalyn's hospice provider and shared that correspondence with The Republic.

For a month, Estalyn had a roommate who was lucid. The roommate told her family that she was trying to keep Estalyn safe and trying to help take care of her.

"I would leave every single time crying," Carlyn said. "These people can't speak for themselves, and I don't know how to do it for them."

The last straw was when Heritage Village called Estalyn's son and told her she had fallen, but that she was fine and not to worry. Two days later he and Dellene visited and found her with bruises on her head and an injured wrist.

No one on staff had taken her to the hospital, so Dellene and her brother did. Doctors discovered Estalyn's wrist was broken.

“I don’t think they had enough people. The workers seemed overworked, the laundry lady seemed to do the nurse’s work,” Dellene said. “I think they hired people that just didn’t care.”

The family moved Estalyn out in July 2022. She came home with night terrors about someone on top of her, hurting her.

Carlyn filed complaints about Heritage Village with Adult Protective Services and the Arizona Department of Health Services after her mom broke her wrist. No one called her to follow up.

"I felt angry and sad and helpless, and the state doesn't make it easy. It's a confusing system, not understanding what power you have, what options you have," Carlyn said. "It seems like no one is listening."

The state found that some of the facility’s employees were not trained in fall prevention and recovery when a state investigator visited to investigate Carlyn's complaint last fall.

That visit resulted in a single $250 fine, though it's not clear what the penalty was for. The inspector found the manager hadn’t confirmed four caregivers had the skills and knowledge to do their job.

Dellene scoffed at the fine.

“That is ridiculous. That is nothing,” she said. “They don’t have to take accountability for what happens.”

Management company promised ‘WOW’ experiences

Madison Realty fired Heritage Village's management company last fall because leadership wasn't "totally happy" with its performance, Langendoen said. He said he believed employees needed more training and more empathy for their colleagues and their residents. But he downplayed the severity of the facility's record.

Langendoen said part of the reason why Heritage Village has had more citations than other facilities is because its eight buildings previously were licensed separately. That means state surveyors reviewed every building as a separate entity so the facility would get more inspections than others.

“If the food menu wasn’t prepared a week in advance, it was prepared five days in advance, they’d write that up eight times rather than once so it was causing a whole lot of … excess or more than normal surveys,” he said. “That was wasting time for both our staff on-site and wasting time for the state surveyors.”

But The Republic found no instances like that in Heritage Village's citations. This year, two separate buildings were indeed cited for the same type of food menu-related problem on the same day. But same-day, duplicate citations issued to different buildings only account for 14 of 148 citations, according to a Republic analysis.

And food menu issues were the least of the facility’s problems.

The state has cited Heritage Village for employing caregivers without evidence that they were qualified for the job, without proof of checking references, without valid fingerprint clearance cards and without proper CPR training.

Management has let unlicensed caregivers work solo with residents and even hired one whose certificate was faked and another whose certificate was dated before the program they’d claimed to attend opened, according to state citations.

During one state inspection, residents in memory care didn’t have call lights. Staff told a state investigator they hadn’t given residents a lanyard, bell or pull cord because they wouldn’t have the cognitive ability to ask for help.

A worker didn’t have a key to a door that locked, allowing a resident to walk into a room, lock the door from the inside, open the window, crawl out and run to an overpass to hitchhike.

Employees also didn’t follow doctor orders on medications.

One resident didn’t get prescribed asthma medicine for an entire month. Another was given Narcan, the medication that can reverse opioid overdoses, for “allergies.”

A surveyor looking at medical records found that employees double-dosed a resident's Tramadol, an opioid that can be lethal if too much is taken. They insisted on a phone call that they didn't double the dosage — but couldn't provide the inspector with proof.

A caregiver, instructed to give a resident medicine to lower blood pressure when the pressure was high, instead only gave it to the resident when the blood pressure was low.

All of this happened in the years after Anita Ferretti — who had struggled with dementia for a decade — killed her roommate Joyce Dinet at Heritage Village when a caregiver skipped a dose of the Lorazepam medication she needed to keep calm.

The management company that Madison Realty fired, SAL Management Group, says on its website that its caregivers “deliver ‘WOW’ experiences.”

Its directors did not respond to requests for comment.

‘She mainly wanted the home to be held accountable’

The state has investigated at least 50 complaints against Heritage Village since Joyce Dinet died and substantiated about half of those. Heritage Village’s citations came from a combination of those visits and general inspections not triggered by complaints.

If the state surveyor determines a facility didn’t break any rules, or can’t find evidence, the Department of Health Services will not post any details about the allegations.

How thorough the investigations are is unclear. The Republic wanted to ask the Department of Health Services leadership if they ever talk to families or review police records as part of their investigations but state officials avoided an interview.

A former health department spokesperson couldn’t even discern whether the state investigated the Brookdale North Mesa assisted living center. The facility had placed Anita with a new roommate several weeks after she killed Joyce at Heritage Village. The second roommate, who was 101 years old, was found on the floor with a broken arm and said Anita pushed her.

There were no witnesses, but the roommate's family had previously expressed concerns about Anita to management. The roommate died a month later, though her broken arm was not listed as her main cause of death.

The former spokesperson had told The Republic the state received a complaint about that, investigated and found nothing wrong. But after his last day working there, a different state spokesperson said he was incorrect.

There was no complaint. And no investigation.

AARP’s Kennedy said the state should publicly report all the allegations made against a facility.

The information is available to those who submit a request for it specifically, but receiving the documents can take months. Asking for and getting police reports also can take months.

“It shouldn’t be that you need to get police reports and do public information requests to find out what’s happening in a facility if you’re thinking of placing a loved one in it,” Kennedy said.

Police officers sometimes note concerns about resident care in their incident reports, even in some cases that the Arizona Department of Health Services didn't substantiate.

Police records show that a month after Joyce's death in late 2019, a woman called to report that her 72-year-old mother who lived at Heritage Village had an inexplicable knee injury, wasn't bathed for 11 days and her nurse found her catheter was dirty. The nurse said it appeared the facility wasn’t properly cleaning it. The woman got a urinary tract infection, wound up in the hospital and then died from toxic metabolic encephalopathy related to Alzheimer's disease.

Her daughter told a Mesa detective she “knows there isn't anything that can be done to bring her mother back, but she wanted to make sure Heritage Village wouldn't be able to do this to anyone else in the future.”

She described the care "as a classroom which had a new substitute teacher every day and that teacher had no idea what the class worked on the day prior."

The detective wrote that he told the woman it would be difficult to file neglect charges as "it appeared there isn't a particular person at fault, but rather the entire staff/system at Heritage Village facility failed."

She said she understood.

"She mainly wanted the home to be held accountable," the detective wrote.

He told her Adult Protective Services might help, though an agency employee told him afterward that the Arizona Department of Health Services and the Ombudsman's Office investigate facilities.

The Adult Protective Services employee concluded there was no neglect and closed the investigation. The daughter said she might take her concerns to court — her only avenue left at that point.

The police detective also closed the case. He noted that the woman had a valid complaint but he couldn’t establish a crime. The facility had no records to explain the woman's knee injury and there wasn’t medical evidence that the urinary tract infection had anything to do with her death, according to the police report.

A few months later, another woman called the police because her mother’s hospice nurse found bruises on her face. Her mother had fallen several times already at Heritage Village, twice on her face and once breaking her collarbone.

A Mesa police detective was assigned to the case and noted that he tried to contact the facility’s superintendent for months, to no avail. The superintendent’s secretary had confirmed that she’d gotten the messages, the detective wrote.

Adult Protective Services got the facility's records for the woman. The police detective reported they were inadequate, with no daily observations or nurse and doctor reports. He concluded that the woman received "substandard" care but found no probable cause that a crime was committed.

Department of Health surveyors were unable to substantiate complaints made on behalf of both of these women — meaning they couldn’t find evidence that Heritage Village broke rules when they investigated months later.

Thus, none of the details about their cases are on the state's search tool people may use for vetting facilities. The Republic found out about these cases by reviewing hundreds of police reports about assisted living and nursing home incidents statewide.

Even when the state cites a facility for a problem, at times the description in the public record is so vague that consumers wouldn’t know how severe the issue was.

Months after Joyce died, police arrested a Heritage Village employee after an 85-year-old resident with dementia was raped.

The only regulatory document that references the man refers to him “inappropriately touching” a different resident. There was no mention of the rape.

And the only penalty for Heritage Village from the Department of Health Services was a $500 fine for failing to ensure the facility had a “manager, caregivers and assisted caregivers with the qualifications, experience, skills and knowledge necessary to ensure the health and safety of a resident.”

The employee was fired, pleaded guilty to three counts of attempted sexual assault and is now in prison.

Police called to chaotic scene; state regulators unaware

Facilities have to report suspected abuse, neglect or exploitation either to police or Adult Protective Services, but neither of those entities investigate whether facilities are breaking rules about quality care in assisted living.

So some traumatic events fly under the Department of Health Services' radar, even though that's the agency that licenses these places.

That's what happened last year, when police responded to a phone call from employees at Heritage Village who had locked themselves in the bathroom with a resident to hide from another resident who was hurting people.

A man with dementia had hit a woman in the face several times. When workers tried to intervene, he intimidated them, and so they grabbed the woman and fled to the bathroom, barricading themselves.

Officers arrived while the man was standing barefoot in the front doorway of the building. His long-sleeved shirt was backward. A radio on the kitchen counter was blaring, the lights were off and a woman inside was screaming.

Officers found a man trembling in a chair at a dining table in the living room area, blood trailing from his eyebrow. He frantically stood up and tried to avoid them, but they assured him it was OK and they just wanted to talk.

He held a shaking hand to his chest. An officer asked who hit him.

“One of those guys you’re not supposed to deal with here.”

When a different officer tried to ask more questions, the man muttered something about someone trying to lock him out in the cold.

He told the officer he was afraid.

“One of them hit me.”

One officer went to the room of the man who’d hurt the others. He found a woman in one of the beds, balled up under the covers, the blanket pulled up to her chin.

She had a black eye.

An employee said it wasn’t the woman's room, that she walks around sometimes and goes into other people’s spaces. She told the officer that she noticed the woman’s injury when she started her shift, and that the same man who had hurt two others that night had hurt her.

The officer asked if she thought to call the police.

She and her co-worker started talking over each other, but she ultimately said she didn’t have time, because the resident who had hurt the woman was “walking around crazy.”

Her co-worker interjected and said the woman had had the black eye for two days.

A former employee who had worked earlier that day, Brittani Navarro, told The Republic that she'd given the man who had hurt others his psychiatric medicine during her shift but saw that he hadn’t received any doses for the previous five days.

The Department of Health Services has no record of any of this.

‘The cost of doing business’

Critics say the state's financial penalties pale in comparison to the money that companies, some of which are real estate investment firms, make off their residents.

During a September meeting of a state council that reviews regulations, a Department of Health Services official said medication errors causing significant harm or even death usually result in one of the harshest penalties officials can levy: a notice of intent to revoke a facility’s license.

But that didn’t happen to Heritage Village when Joyce Dinet died in 2019, nor after the 14 other medication-related errors in three years. It is not clear to what degree residents were harmed by each of the subsequent errors. The errors range from poorly documented medicine logs to skipped or inaccurate doses.

The facility paid the state $500 four months after Joyce died, for failing to ensure staff had “qualifications, experience, skills and knowledge necessary to ensure the health and safety of a resident.”

The fine associated with Joyce’s death is typical.

State law prohibits the Department of Health Services from fining facilities more than $500 per deficiency each day that it occurred — but the department intends to propose legislation to increase the amount, according to a letter to a review council member.

The official at the review meeting, Residential Facilities Licensing Bureau Chief Tiffany Slater, said first-time offenders typically pay $250, repeat offenders pay $500, “and then it escalates into legal orders.”

Heritage Village’s steepest fine — $4,500, mostly because six employees didn’t have complete personnel files in the summer of 2022 — was roughly the cost of a single memory care resident’s monthly rent.

Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes recently told The Republic her office may turn to civil and criminal prosecution to hold accountable facilities jeopardizing their residents. The state fines are “meaningless,” she said.

Many assisted living facilities are part of large for-profit companies with influence in multiple states.

“A $500 fine from (the state) is a slap on the wrist and is considered the cost of doing business for some of these folks,” Mayes said.

Langendoen told The Republic that, while his team “doesn’t like paying fines of any amount,” the recent changes at Heritage Village were unrelated to fines.

“We made improvements because we wanted to improve,” he said.

Madison Realty Companies, with offices in Denver and Pasadena, has acquired and managed more than $6 billion in real estate across 30 states, according to JRW Investments, a company that evaluates investment opportunities.

Madison's website says it “purchases properties below market value when possible. We upgrade or expand properties to add value to our investors’ capital.”

An undated video featured on its website extols a Colorado assisted living project predicted to generate “significant returns” for investors. Madison would add more rooms to collect more rental income, add “special memory loss rooms as these residents pay higher rents” and get low-interest government loans designated for senior properties.

Langendoen said in the video that his investors like senior assisted living projects because there’s more demand than supply.

“What we have is continuing demand driving rents higher,” he said.

The narrator then described the company’s cash flow.

“Seniors living in these high-end assisted living facilities have significant funds from savings, along with life insurance proceeds from their spouse and the sale of their home. Plus Social Security and retirement programs may also provide an additional $3,000 or so per month of income.”

‘The government is clearly failing the people of Arizona’

Choosing an assisted living facility for a loved one is one of the most difficult decisions a family can make. Yet researching choices can be so daunting and confusing that some families wind up picking a place without the full picture.

"Why is it so hard for someone like me to find out everything you know?" Carlyn, the daughter of Estalyn Bouchard, asked The Republic. "It shouldn't be that hard for someone like me to research these facilities."

The average consumer may not know that Heritage Village had more than 100 citations if they search AZCarecheck, the state’s website that posts citation and penalty information about care facilities.

When searching for "active" facilities, which is the default setting, no penalties are listed and the only visible citation for Heritage Village is for skipping its annual payment to the state to keep its license up to date.

When The Republic asked why, a health department employee said people need to take an extra step.

Over the past year, Heritage Village consolidated its separate licenses into a single license. That resulted in the state listing its old licenses under “closed” facilities.

That means consumers would have to know to set their search for “closed” buildings — even though the buildings are not closed.

This occurs for any facility that gets a new license.

The Health Department doesn’t make it easy for people to find out what happened to their own complaints, either. Carlyn received a letter in June instructing her to go online and look up a citation report dated Oct. 12, 2022, pertaining to her mom’s investigation.

The letter does not explain what investigators found, and offers no instruction on how to find the citation report or any associated fines, which are posted under the facility’s “closed” licenses.

Carlyn said she would never think to search for “closed” facilities to find information on open facilities.

A Health Department official said in an email that they "understand the person who filed the complaint is likely facing difficult challenges."

"However, as the regulating agency, ADHS is legally restricted in what information we can release, and that information is made public on AZCareCheck.com," said Cindy Graham, deputy bureau chief for the Bureau of Residential Facilities Licensing. "We are prohibited from providing any additional information."

Kennedy, AARP’s Arizona director, said the government is “clearly failing the people of Arizona.”

“Nobody would place their loved ones in a facility with 150 citations if they knew,” Kennedy said. “The government’s largest role is to make sure that it protects people.”

This story was updated to reflect new information from the Department of Health Services about whether a complaint and investigation happened at Brookdale North Mesa.

Arizona Republic reporter Sahana Jayaraman and former Republic reporter Geoff Hing contributed to this report.

Reach Caitlin McGlade at caitlin.mcglade@arizonarepublic.com. Follow her on X, formerly Twitter, @caitmcglade.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Heritage Village: Injuries, death at Mesa senior living center