Arizona may expand involuntary psychiatric care — even with a flawed system. What to know

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Republican and Democratic lawmakers want courts to be able to put more Arizonans under involuntary psychiatric care.

Several bills have already passed the state Senate or House on bipartisan votes, producing unlikely allies across the political aisle.

But the bills have also brought together unexpected opponents — it's not an issue that falls strictly on party lines. Critics of the plans worry about the civil rights of patients and that proper resources for staffing and treatment won't follow an increase in court-ordered commitments, resulting in unfunded mandates.

Sen. Justine Wadsack, a Tucson Republican and member of the conservative Freedom Caucus, teamed up with Democratic Sen. Catherine Miranda of Phoenix for Senate Bill 1578. The legislation allows family members to petition for the involuntary treatment of people debilitated by drug abuse. It cleared the Senate last week.

"I understand that there is a lot of reservation with the word 'involuntary,'" Wadsack said on the Senate floor, adding she prefers the term "court-ordered treatment."

"This allows somebody to say, 'This person is in need of help. They need to get treatment,'" she said. "It gives them a longer period of treatment, and it is not forever."

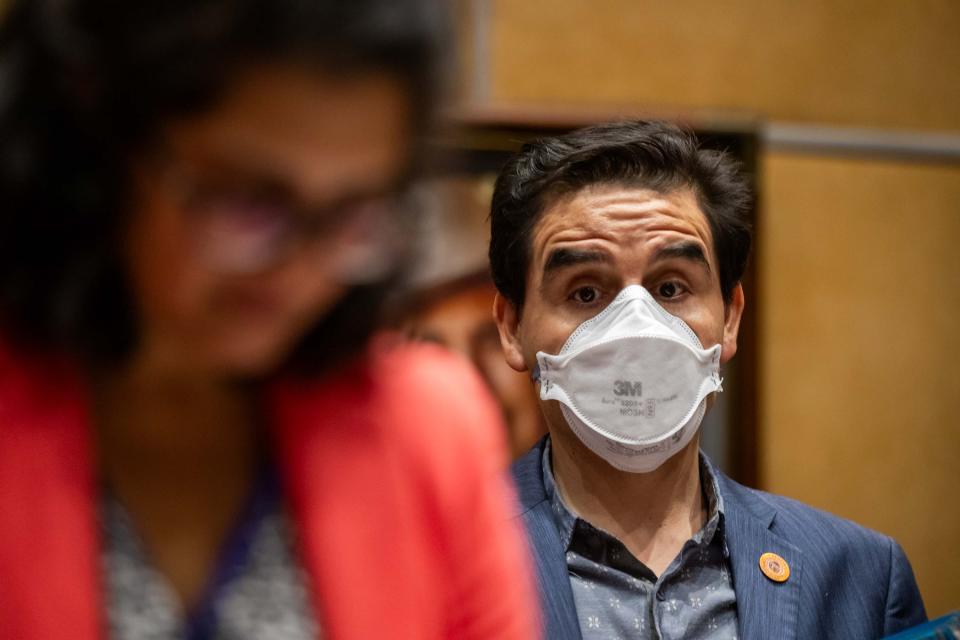

Sen. Juan Mendez spoke against the measure, citing his firsthand experience.

The Tempe Democrat said his family petitioned for involuntary treatment for his younger brother, who was diagnosed with severe mental illness and developed a drug addiction. Mendez was emotional as he related on the Senate floor last week how "forcing my brother through this system had deep psychological and emotional consequences for my whole family."

"Honestly, I don't know what I would do if I had to do it again," he said. His brother's experience at Arizona State Hospital was so "full of underpaid staff and guards who were constantly sedating him" that he came to view the involuntary care option as a "joke."

"Forcing more people into it is just going to cause more problems," Mendez said.

Sen. David Gowan is a Sierra Vista Republican who's devoted his attention to the topic this year. He told The Arizona Republic new medications and approaches for treating mental illness, plus video cameras and other technology in the facilities, would help avoid abuses.

"At the end of the day, I think we should build our state hospitals up," Gowan said, adding that Arizona could become the "model" in treatment for the rest of the country. "Families are asking for this."

Experts say Arizona lacks behavioral health capacity

Arizona has fewer state-operated beds that can be used for non-criminal patients, per capita, than any other state, according to a state report released in September.

The Arizona State Hospital has only 116 beds reserved for civil psychiatric patients — those who aren't awaiting trial or have been convicted of criminal offenses. The beds are portioned out to the state's tribal communities and 15 counties, and a consent decree from the groundbreaking Arnold v. Sarn lawsuit limits the number of civil beds for Maricopa County to 55. Experts say up to 2,200 people in the county could qualify to be housed there.

People with serious mental illness often enter the health care system after committing crimes or having a mental health crisis that requires emergency treatment. After jail, they may be taken to a behavioral health care facility — often Maricopa County's Valleywise Health — where they get medications and treatment to stabilize their condition. The average stay in these facilities is 22 days. But because of a shortage of similar facilities and beds at the state hospital for Maricopa County residents, some patients may end up staying at Valleywise for much longer, sometimes as long as a year.

The lack of enough involuntary beds also means that people who are a danger to themselves and others can be discharged from urgent psychiatric crisis care before getting a bed at Valleywise.

Valleywise currently has 355 beds available for seriously mentally ill patients who have been ordered to undergo involuntary treatment, reporting by The Republic shows, but more are needed.

Secure residential behavioral health facilities are needed, advocates say, to become part of the continuum of care - to give people treatment in a place that's not as high level as a hospital but not as low level as a group home. Some patients, upon being released from the state hospital, need a place as a transition where they can't walk away from treatment.

Patients released quickly from treatment may stop taking their medication or return to self-medicating with street drugs, which leads to more arrests in a process mental health advocates call "treat, street, repeat."

If ordered to the Arizona State Hospital, the goal remains to restore the person to normal function and eventually discharge them. In 2021, the hospital's annual report showed civil patients stayed an average of four years. Patients convicted or awaiting trial for a crime and sex offenders stay longer, from an average of six to 11.5 years. Nearly all are discharged to group homes, with about 17% going to another medical facility or home to their families.

For some lawmakers, it's personal

Several state lawmakers have close friends or family members who are mentally ill or struggle with extreme addiction.

Gowan has a close childhood friend who at age 20 began exhibiting signs of schizophrenia. He also knows someone with serious mental illness in Sierra Vista who had been in and out of jail without adequate treatment — eventually ending up in prison. He said such people need to be placed "where society can take care of them because they just can't do it for themselves."

"This comes from my heart," Gowan said.

Opponents of some of the measures also shared personal stories. In addition to Mendez, Sen. Eva Burch, D-Mesa, also referenced a family member in dire need of treatment.

Burch, a nurse who works with people with opioid addictions, said her brother has been in and out of jail and treatment for opioid use disorder. But she said involuntary treatment wasn't the answer because the state wouldn't fund the type of resources, like better staffing and treatment, to prevent "disastrous" consequences.

Miranda disagreed, telling fellow senators it's a "great bill" for the "sickest of the sick."

Miranda told The Republic that Wadsack's original Senate Bill 1578 was problematic in that it "tried to create an entirely new involuntary treatment procedure" that could have violated patient rights. She provided an amendment that aligns the bill with current procedures. But a bigger difficulty was finding Democratic support for it.

"It gets frustrating when hard bipartisan work is done and the biggest hurdle is your own party sometimes," she said.

Marilyn Rodriguez, a lobbyist who works on behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona, said in a committee hearing last month the bill offers only "false hope" to families because it doesn't provide "the availability of necessary resources for success." She added that people with addictions typically need to "enthusiastically consent to care before that care is any actual help to them."

The bill was mainly supported by Republicans. But in a rare move, another Freedom Caucus member, Sen. Anthony Kern, R-Glendale, joined with most Democrats and the American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona in opposing the bill.

"We do have to find a solution," Kern said on the Senate floor last week before the bill passed 20-10. "I don't like anything involuntary."

Reform sought for Arizona State Hospital

The Arizona State Hospital provides the one long-term residential treatment option for psychiatric patients, but it's also been the source of numerous complaints in recent years related to lack of training and staff shortages. A September report revealed findings like a staffing shortage even as the facility had an increase in "high-risk patients."

Critics of the facility, which began operations in the 19th century as the state's "Insane Asylum," can point to recent incidents that support their concern.

Audio recordings from this year's meetings of the hospital's nine-member Independent Oversight Committee describe assaults, sexual violence and self-harm by patients like hitting themselves or eating laminate from cabinets.

Reading from an internal report on Feb. 22, a committee member described how a patient came out of a room with blood "running down their head and eyes and clothing, and they were confused." A behavioral tech who tried to help couldn't understand what the patient was saying. A doctor ordered the patient to be taken to a medical facility.

Another dangerous situation for patients centers on "how many unwitnessed falls we're having," the hospital's CEO, Michael Sheldon, told the committee. "This is something we're tracking very closely."

This is the third year Gowan has attempted to take the state hospital out from under the state health department and create a five-member governing board that would be appointed by the governor. Under his Senate Bill 1688, the board's main responsibility would be its independent hiring of a director for the hospital.

The bill failed last week on a vote of 13-15. Two Democrats, Miranda and Sen. Sally Gonzales of Tucson, voted in favor. Democrats who voted against were joined by Kern and Wadsack, who said they were concerned about the quality of board members Democratic Gov. Katie Hobbs would appoint. Wadsack told The Republic she otherwise would "love" the bill and hoped to work with Gowan on an amendment to adjust the appointment of board members.

"It's super disappointing," said Will Humble, a former state health director who is now executive director of the Arizona Public Health Association, after the vote. He likes Gowan's idea, saying it's needed to prevent the ongoing "conflict of interest" in which the state health department both runs and regulates the state hospital.

"Until you change the accountability structure, there's no reason to believe things are going to get better," he said.

The bill is scheduled for possible reconsideration this week.

Funding challenges

While some supporters of the bills are optimistic about the legislative session so far, they say the struggle for reform won't end soon, especially with this year's state budget deficits. Most of the mental health bills put forward this year don't include any funding.

"We were challenged to find bills that didn't need money," said Rachel Streiff, the leader of a new and vocal group of parents and guardians called Mad Moms. "In other words, what could we fix in the current system that's not going to cost anything?"

Gowan's Senate Bill 1678 is one such piece of legislation. It refines admission qualifications for psychiatric patients in facilities known as Secure Behavioral Health Residential Centers. A law that went into effect in January allows judges to commit patients to the centers.

But there are no such centers, because there's no funding for them. Supporters hope the bill will encourage their construction someday. The bill passed the Senate 19-9-2.

Senate Bill 1682 from Gowan would allow Maricopa County patients ordered to treatment in the state hospital to use beds left vacant by smaller counties. It passed the Senate on Feb. 22 on a vote of 18-11-1 and moved to the House.

Another bill, House Bill 2744, sponsored by Rep. Consuelo Hernandez, a Tucson Democrat, clarifies the rights of guardians to better include them in court-ordered treatment decisions for adult patients. It passed the House on Feb. 26 with strong bipartisan support.

Reporter Stephanie Innes contributed to this report.

Reach the reporter at rstern@arizonarepublic.com or 480-276-3237. Follow him on X @raystern.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Why Arizona wants to expand its flawed involuntary psychiatric care system