From the archives: Urban renewal reshapes the Louisville landscape

From the early 1960s to the late 1970s, the Courier Journal covered the federal government program commonly known as ‘urban renewal’. Established by Congress in 1949, it sought to revitalize urban areas in decline.

Dilapidated buildings in city centers were lessening tax revenues as people began shifting to the suburbs for better houses and retail shops. This federal program began in Louisville in 1962. Its history has been debated as to its successes and failures.

As reported in an Oct. 22, 1963, article, the agency was considering properties to be targeted for replacement with newer buildings. One such location was the former Presbyterian Theological Seminary campus at Broadway and First Street. Fortunately, the agency declined saying ‘sure somebody will find a good use for it’. Today, it is the signature image of Jefferson Community and Technology College.

By 1964, doubts were starting to surface as to the results of this program.

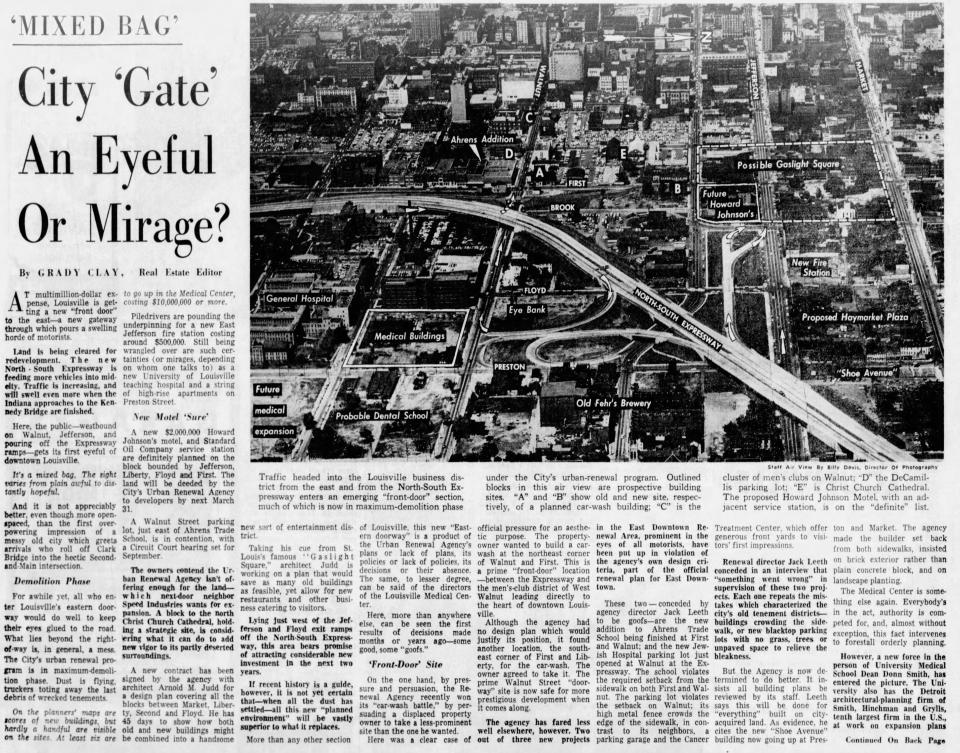

“It is not yet certain that, when all the dust has settled, all this new planned environment will be vastly superior to what it replaces," a Courier Journal article published Aug. 9, 1964, states. Several cleared areas had become parking lots and the agency set forth guidelines that future parking surfaces were to include grass areas, trees, and unpaved space to ‘relieve the bleakness’.

Robert Weaver, administrator of the Housing and Home Finance Agency, in a lecture at Harvard in April of 1965 stated that initial advocates of urban renewal had 'oversold its potential to local governments. Until there is some consensus about the basic objectives and possible goals of urban renewal, it will continue to be surrounded by confusion.'

To illustrate this "confusion," or maybe a better term might be "controversy," the Courier Journal ran a national article that focused on the Urban Renewal program in Towson, Maryland, where residents were in open revolt.

The citizens voted down a bond ballot measure that was to fund the new projects being proposed. Both liberal and conservative groups were united in opposition. Civil Rights groups challenged removal of minority residents while conservatives opposed taking of private land by condemnation along with the "higher taxes" that would result.

Many felt it increased profits for real estate developers and banks, and preferred larger national businesses over smaller locally owned shops.

Louisville’s urban renewal proposed reconnecting downtown to the riverfront. A massive residential and office complex was to be built in the area between Fourth and Sixth Streets, north of West Main. To accommodate this large footprint, all the existing buildings were to be demolished, including the Columbia Building, the city’s first skyscraper built in 1890.

The Columbia was a dramatic distinctive landmark with an ornamental stone edifice. For a variety of complications, this project did not happen but the demolition did. Today, the Belvedere, Galt House, Kentucky Center for Performing Arts, and several modern office buildings are at this location.

“When people speak of urban renewal, they automatically see a bulldozer coming at them down the street, and this is all wrong. Urban renewal is an all-inclusive thing. Conservation and rehabilitation play a very large and intricate part of it,” Jack Leeth, agency executive director was quoted in a Nov. 12, 1967, Courier Journal article. In this same article, it was noted that the agency only saved 17 structures and demolished 2,463 buildings.

Leeth "won’t disagree" that earlier statements "promised more than was delivered."

A March 11, 1974, story quoted Allan Steinberg, who was a director of student life at Jefferson Community College: “For many years, Louisville didn’t change its face. Then, all the sudden with urban renewal, the resurgence of the riverfront, they said: ‘What’s happening to Louisville?’ But when they looked up to see the new buildings, they also saw the old ones and liked them. Just because a structure is old, it shouldn’t necessarily be saved. You need to have new buildings to give people in a city that sense of a flow of time. But, let’s not destroy all of Louisville for the new.”

When the urban renewal program was concluding in Louisville in 1978, Courier Journal reporter Sheldon Shafer did an exit interview with Jack Leeth to summarize the achievements and some of the controversies.

Leeth said the agency redeveloped 2,000 acres of land, spent $100 million in federal grants for new homes and apartments, facilitated more than $500 million in new public and private construction on cleared land. He said 5,000 families were relocated to suitable housing and 500 merchants were resettled.

"Urban renewal — often derided as urban removal — has been criticized locally because the large sections of homes and businesses it cleared out often were where minorities lived," the April 2, 1978, story read.

Leeth emphasized urban renewal revitalized the waterfront, helped create the Medical District east of downtown, and built government buildings and public housing to the west of downtown as well as assisted expansion of the University of Louisville. Only urban renewal could have revitalized these areas according to Leeth. But, considering the extensive impact of urban renewal, friction was inevitable, he stated.

As to removal of popular black-oriented night spots on Old West Walnut Street, Leeth said few of the buildings met all the building, fire, and safety codes. “No one likes someone telling them what to do. We understood that.”

Regardless of how one feels about the ultimate results of urban renewal, none can dispute the 1978 headline of reporter Shafer’s article: “Changed city is left behind by chief of urban renewal."

Steve Wiser, FAIA, is a local historian, architect, and author.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: From the archives: Urban renewal reshapes the Louisville landscape