How an archaeological dig helped a North Texas man learn about his great-great-grandfather

When archaeologists uncovered a 19th-century blacksmith shop owned by an African American community leader named Tom Cook in northwestern Denton County, they did not just contact his great-great-grandson, William "Howard" Clark, with the news, they hired him.

"They told me to bring along my weed eater and chainsaw," Clark says with a laugh. "I didn't know I was going to be an active part of it. I got to dig dirt and collect artifacts. It was more fun than a nearly-60-year-old-man should have."

In addition, Austin-based archaeological team leader Doug Boyd brought on a practicing blacksmith from the area, Kelly Kring, and drafted Clark's daughter to reach out to the local African American community.

"It is the only Black-owned smithy ever found and excavated in Texas," Boyd says. "There might others somewhere in the U.S., but we haven't found out about them."

Meanwhile, Maria Franklin from the department of anthropology at the University of Texas gathered insights from Denton County's Black community to put the artifacts into historical context.

"I wasn't sure what to expect," says Clark, a retired Denton County sheriff's deputy, about joining Boyd's team that was subsequently purchased by Stantec, a global company that integrates design with services that include archaeological work. "I had some idea it would be like 'Indiana Jones.'

More: Want to see 2 million years of life? Visit the Lubbock Lake Landmark archaeological dig

"But the team built up a trust. They didn't talk over my head. I gobbled up the findings."

That's exactly what "collaborative community archaeology" can do. Instead of treating found material as cold mysteries that only certified experts can decipher, this increasingly popular branch of the field enlists the people directly affected by the discoveries — especially descendants and their communities — in the process.

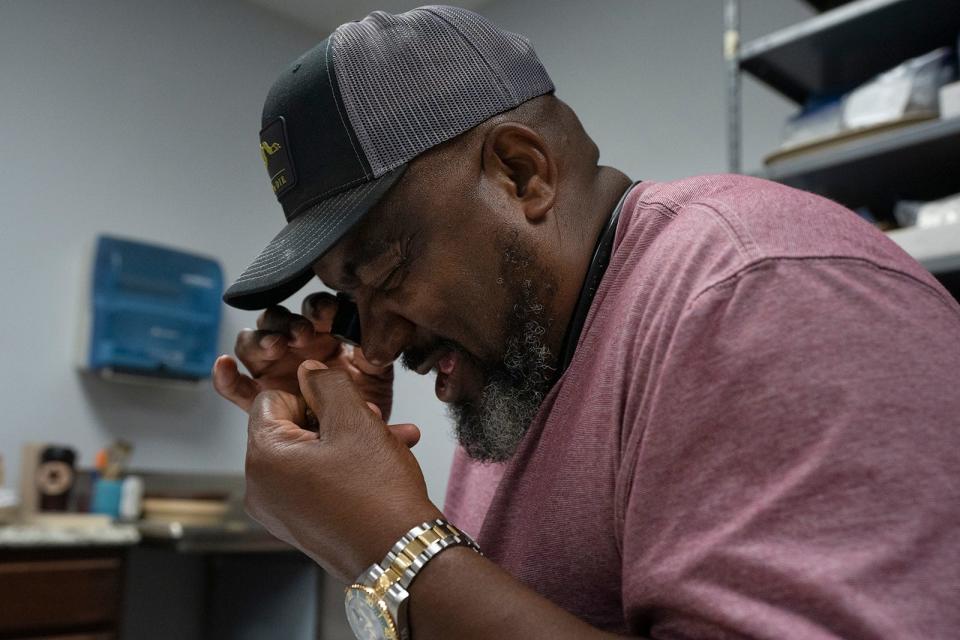

"Once they found my great-great-grandfather's gravesite," Clark says, "I began to think of the part of me that's in the ground. I kept expecting to look up and see an old man looming over me.

"This is as close as I can be to my great-great-grandfather — on this side of life."

Putting community archaeology into action

Tom Cook's blacksmith shop and a nearby hotel stood at the center of the Bolivar settlement, founded as New Prospect in 1859, and renamed after Bolivar, Tennessee, in 1861.

Cook operated the forge during the last three decades of the 1800s next to the small Sartin Hotel, not far from the Chisholm Trail. He continued his work there even after 1886, when many Bolivar residents moved four miles away to the town of Sanger, which had been connected to the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railway.

Bolivar was home to 150 residents at its peak. Today, about 40 people live there.

More: More than 50 million artifacts from Texas’ past kept at UT lab

When it came time, 120 years later, for the Texas Department of Transportation to widen FM 455, instead of just plowing through — the kind of thing TxDOT might have done in the past — the state agency hired an Austin firm, now part of Stantec, recognized for its sensitive strategies for discovering and interpreting historical material.

Why the old practices had to change

In Texas, archaeological sites and historic buildings located on private land are tough to preserve and regulate, despite well-known federal, state and local laws and ordinances. Many times, owners of private property have the last word on how to dispose of what is found there.

Public land is another story.

The federal government acted ahead of Texas in this regard. The U.S. Antiquities Act of 1906 preserves historical and archaeological sites located on federal land. More laws passed in 1979 and 1990 go further to protect specific kinds of archaeological resources and Native American graves.

More: Texas history: We turn the clock back 20,000 years at the Gault Site in Central Texas

In Texas, much of the law regarding sites on government land was enacted because previous regulations, if any, were too loose.

The 1969 Antiquities Code of Texas, for instance, came about because of a Spanish treasure ship that was plundered in the late 1960s in state waters. Since efforts to raise the sunken treasure by a private firm lacked serious archaeological controls, much historical data was lost.

The 1969 Code ensures that Texas state agencies — along with cities, counties, school districts and other government entities — notify the Texas Historical Commission of any "ground-disturbing activity on public land and work affecting state-owned historic buildings."

This includes, especially, roadwork. Which is why TxDoT is often involved.

Recently, for instance, the state agency backed off a proposal to expand Interstate 35 into burial sites at the Mt. Calvary Catholic Cemetery in Central East Austin. Ted Eubanks, a certified interpretive planner, looked more carefully at the site and found that many of the city's prominent immigrant ancestors were buried there. TxDoT did the right thing and changed plans.

How bad were pre-Code practices?

One pre-Code case that went spectacularly wrong dates to 1946 when TxDoT announced it would build the first freeway in Dallas.

As detailed in a Sept. 17, 2021, story filed by Megan Kimble in the Texas Observer, a 1869 freedom colony on the outskirts of Dallas included a slave-era cemetery. The planned freeway route cut right through the cemetery.

Construction displaced some 1,500 structures, many of them owned by African American families, as well as many graves.

More: Texas History: Spelling out life on an 1800s Texas plantation

In 1987, TxDoT announced that it would expand a 10-mile stretch of the highway. They found that the original freeway had paved over more than 1,000 graves of enslaved people and freedmen. Headstones had been used as rubble to fill ditches.

In 1993, the state agency exhumed the remains and reburied them at nearby Freedman's Memorial Park. The city of Dallas hired Black sculptor David Newton to build a memorial for the desecrated graves, which was dedicated in 1999.

How to honor the past the right way

Contrast that Dallas debacle to what Boyd and his team previously did for a farmstead that belong to freedman Ransom Williams in far southwestern Travis County, as described in an American-Statesman story on Sept. 24, 2016.

It became a model for what the team later did with the Cook blacksmith shop and for other community archaeology projects.

In 2003, a TxDoT surveyor discovered an old chimney while working on the right-of-way for the planned Texas 45 extension not far from the border of Travis and Hays counties. The highway would go right over the remote farmstead.

More: Unprecedented history unearthed at freed slave’s Travis County farm

Boyd's team dug more than 25,000 objects from the time when Williams' family lived there from 1871 to 1905. It was a rare find that should change the way historians look at the daily lives of freedmen farmers and ranchers.

After only a few years of freedom, Williams had accumulated enough resources to buy more than 45 acres as well as a corral full of horses. Later, as the dig would indicate, the family could afford delicate jewelry and imported dinnerware.

Of special significance, nobody had lived on the land after the Williams brood moved into the city, so diggers could be certain that almost anything found there belonged to the family.

UT students and professors carefully combed through African American newspapers dating from the period at the Briscoe Center for American History, while they contacted and interviewed more than 25 descendants.

One was Jewel Andrews of Austin.

“I will never forget the look of amazement on Jewel Andrews’ face as Maria Franklin (another archaeologist) and I gave her a tour of the farmstead where two generations of her family once lived,” Boyd told the American-Statesman in 2016. “The history of the Williams family and their Central Texas farmstead is not one you will find in any Texas history book.”

Tom Cook: a property owner, a leader in his community, a pastor and a freemason

After doing a preliminary survey of the Bolivar site, TxDot contacted Boyd's Austin-based team in 2020.

The hotel and blacksmith shop dated back to the late 1860s or early 1870s. Interpreting the rough limestone hotel was pretty straightforward, but the forge challenged the team's expertise. Working blacksmith Kring, who teaches the craft at area schools, joined them in the field.

"We didn't know what we were looking at," says Alex Menaker, an archaeologist on Boyd's team.

More: Texas History: Sizing up daily lives in the state’s freedom colonies

Among the first things that they learned to search for was "hammerscale," pieces of metal sized from the microscopic level to about a quarter inch long. This is what flew off of the tools and other metal objects during the smithing process and ended up in the soil.

"We found magnets that could detect the tiny hammerscale particles," Boyd said. "Each little piece of waste iron tells a story of 'cold cuts' or 'hot cuts' or 'drops,' things that get cut off and drop to the ground."

"Next we are asking: 'Where was his coal coming from?'" Menaker says. "We found slag, clinker and coke. We hope to source the coal and the clay by using X-ray flourescence. That way we can map out the relationships among the users.

"One answer allows us new questions," he continues. "Eventually, we could determine the 'blacksmith's shadow,' the negative space where the blacksmith stood while working."

Going through records, they found that Cook started working at the shop under a British blacksmith in 1872, then he purchased it in 1882. He died in 1898. That long length of time — 1872-1898 — complicated any interpreting.

"When people live in a place a long time," Menaker says, "things get messy."

More: 'We didn't let this place die': St. John Colony, Texas, endures for 150 years of grace

Meanwhile, anthropologist Franklin found that seven of Cook's children grew to adulthood. Some owned land in Denton, especially in the Quakertown neighborhood, where African American families lived.

This freedom colony was displaced in 1922 — a year after the 1921 Tulsa Massacre — because it was considered too close to the school that became Texas Women's University.

"We found place names relating to people in the Cook family story," Franklin says. "We also found their names on bricks. Tom Cook was not just a blacksmith. He was a property owner and a leader in his community, a pastor and a freemason."

Franklin's team went from door to door and conducted oral histories.

They also found a 1918 collection of reminiscences of an old rancher who recalled the "best citizens" who "never failed to answer the roll call in time of danger." He listed 112 white and 10 Black residents. Tom Cook was one of them.

One of the smartest things the team did was to stage a live blacksmithing demo with Clark and Kring at a Juneteenth celebration in Denton. The event not only helped explain Cook's part in their community, but it also opened up new connections among descendants.

Interpreting every little thing: The work continues

In an Austin work room, four men sift through pieces of metal, ceramics and glass dug from the remains of a 19th-century Texas blacksmith shop as part of an ongoing process to interpret what the team found.

Joking and kidding with ease, they consult old catalogues, such as Sears & Roebuck, and other printed material for clues about the artifacts.

Two of the men are trained archaeologists, another a working blacksmith, and the fourth a direct descendant of the African American man who worked that smithy more than 120 years ago.

All four have been collaborating for years, along with anthropologists, historians and community leaders, to uncover and explain what was found in the ground in a rural part of northwestern Denton County.

They concentrate for a few minutes on a long, thin, curved piece of metal now darkened by time.

"This is part of a nail clinching bar," says Clark, great-great-grandson of the clincher's presumed owner, blacksmith Tom Cook. "It bent the ends of the nails as they were being tapped into horseshoes. I used to see something like that around.

"You can look closer, but always look closer."

Beside iron blacksmithing artifacts, the team found and identified ceramics, glass beads, perhaps from a rosary, and a button from a Union soldier's uniform.

"Numerous manufacturers made Union buttons," Menaker says. "We know that this one came from Scoville Manufacturing in Waterbury, Massachusetts.

"You see, with artifacts like this, we are witnessing the birth of modernity and the growth of capitalism, as well as the shift from the rural to the urban. We identify the artifact, ask what does it mean and how did it get there."

After all, Cook worked this blacksmith shop during Reconstruction. Union soldiers were stationed all over Texas. In Travis County, Ransom Williams owned a Union jacket at one time.

"You can't deny the materiality of it," Menaker says. "You can't deny its existence."

As part of the team's public outreach, the story of the Bolivar dig will eventually appear on the "Texas Beyond History" website, which already hosts the story of the Ransom Williams farmstead.

"This may be all that's left," descendant Clark says about the mute objects on the work table "but it's enough to get the story of their lives. The worst thing would have been not to follow up."

Michael Barnes writes about the people, places, culture and history of Austin and Texas. He can be reached at mbarnes@statesman.com. Sign up for the free weekly digital newsletter, Think, Texas, at statesman.com/newsletters, or at the newsletter page of your local USA Today Network paper.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Interpreting a rare find of African American blacksmith shop in Texas