'I was treated like a criminal': How Britain turned its back on West Indies great Collis King

England was the scene of Collis King’s greatest moment as a cricketer and, for 44 years, the country he has called home, along with his native Barbados.

But King, who helped the West Indies to one of their most famous triumphs – the 1979 World Cup victory at Lord’s – now feels his adopted country is treating him like a "criminal" after being effectively deported on a technicality surrounding a visa application.

King is currently stuck in Barbados, separated from his British wife and unable to return to England to play league cricket for Dunnington in Yorkshire where, at the age of 67, he still stars with the bat and gives up his time to coach locally in the area.

After a professional career which included nine Tests and 18 one-day internationals for West Indies – then the undisputed masters of the sport in all its forms – King has become a much-loved figure in the northern leagues of England, scoring more than 50 hundreds and setting records that league officials have said “will never be broken”.”

Now, like thousands of others, he is mired in a legal battle against Britain’s strict immigration laws that recently caused major embarrassment to the Government following the crackdown on the Windrush generation.

It has left him feeling angry and let down by a country to which he has contributed so much, particularly when he had his Bajan passport confiscated by staff at Heathrow before boarding his flight back to the Caribbean – apparently because he was deemed to be at risk of absconding.

“I felt like I was treated like a criminal,” he told Telegraph Sport from Barbados. “It has really shaken me that after all that time that I can’t stay. It really hit me for six.”

King’s problems started when he was here last year and applied for a spousal visa, giving him the right to remain in the country. It was rejected because he had applied while in the United Kingdom on a visitor’s visa. He was told that for a spousal visa he had to apply from his country of origin and was given 14 days to leave the UK.

He had to return to Barbados to start the process again and, after three months of waiting, still has no date for a hearing. He has been told it could take months. The worry for King is that fellow Bajan, Hartley Alleyne, who played county cricket in the 1980s, spent three years waiting for his case to be resolved and some of the Windrush generation cases have been going on for years. A Home Office spokesman said it does not routinely comment on individual cases.

“We tried to get some help at the embassy in Barbados but it is all done online – there is hardly anybody in Barbados to give you any help,” he said. “I have given all the information they asked for and more. I have waited and waited and nothing has happened.

“I have been playing cricket in the UK for many years but I have always come back when my visa stated. I have never stayed longer than I was due to stay. If I had six months to play in the leagues, I would always come back on time. Never once in 44 years have I overstayed my time.

“I was not born a British citizen but I have been going to Britain long enough to feel part of the English set-up. You cannot come to a country for so many years without loving the place. I have been coming and going, loving the country and that is the sad thing, really. I have talked to [former West Indies team-mates] Desmond Haynes and Wes Hall about it and when I tell people what’s going on, they say: 'That can’t be right.' But it is right because here I am, stuck in Barbados not knowing when this will end.”

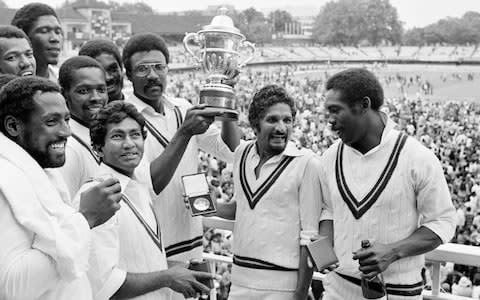

Many of the Windrush immigrants brought with them a love of cricket and in the 1970s and 1980s they had a West Indies team to be proud of. In 1979, King was their hero, with fans running on to the pitch at Lord’s to cheer him off the field after a match-winning innings in the World Cup final against England on a day when he even eclipsed the great Viv Richards, smashing 86 off 66 balls.

King was already a star in the northern leagues and subsequently played county cricket for Glamorgan and Worcestershire, spending the summer in the UK and the rest of the year in Barbados. It was only last year when he decided he wanted to spend more time in the UK with his wife that he decided to apply for a spousal visa. When that was turned down, his nightmare began.

When he flew back to Barbados to restart his application, his Bajan passport was confiscated by Heathrow staff. It was only returned at the top of the airplane stairs when it touched down in Bridgetown.

“It really hit me hard, that experience,” King said. “But now it is all a waiting process. I am a fit person and play club cricket when I can. I love cricket and whether playing years professionally or as an amateur, I have always put something back. I coach voluntarily and it is saddening, really.

“They said the appeal could take four weeks, or it could take 15 weeks. Next month, it will be four months and, of course, there is no guarantee it will be approved. I don’t know how they system works. I can only guess, hope and speculate that things will go right.”

He is not the only cricketer in this situation. Richard Stewart played for Middlesex in the 1960s for three years having come to Britain in 1955 when his sister got a job in the NHS as a nurse. His story echoes that of thousands of others from the Caribbean, believing they had a right to live in the UK only to discover years later they could be sent back to a Caribbean country they barely know. He is facing problems because he does not have a British passport and is fearful of leaving the country and not being allowed back in again.

King has great sympathy for the Windrush generation but admits his case is different, even though he has fallen victim of the same crackdown on immigration numbers.

“The Windrush generation went to the UK and helped rebuild the country after the war. My situation is not quite the same. I sympathise with the people who have gone over there from all of the Caribbean states, done all that work and then after 50 years realise they have nothing. That is really hard,” he said. “I hope the country sticks by those people, they deserve it. It is hard when you live over there for 50 years and then find out you have to go back.”

King’s international career was cut short by the strength of West Indian cricket at the time.

After signing for the South African rebel tours of 1982-83 and 1983-84, he never played for West Indies again. Instead, he made a living playing in the English leagues. He believes there will be other Caribbean cricketers, less high profile than him, in the same situation, having come to this country to play league cricket, settled in the UK but who now find themselves in trouble.

“Yes I am sure there are other cricketers in this situation. It is just not something you expect to happen to you,” he said.