What It's Like to Travel Through 4 Countries In 3 Months With 2 Kids

Coconuts falling on the roof and roosters crowing at 4 a.m. That's our soundtrack to Kauai.

The louvered screens of the bedroom window let in the ocean breeze and the white-noise whoosh of the surf, shot through with those sharp, full-throated calls. On the second night, my husband turned to me and said, "I'm going to kill that rooster."

The roosters were messing with my husband's sanity. Me, I kind of liked them. Chickens everywhere are part and parcel of life in Hawaii, and they came along with the open-air bungalow, the fruit trees, the warm air, the sunshine, the sand from the beach across the road nding its way into my sons' hair at the end of the day.

So began our family's sabbatical summer to Kauai, Hawaii; Hokkaido, Japan; northern Italy; and Norway. My husband, Matt, and I had been planning the trip for two years. It was a way to be together as a family - to adventure with our sons, Felix and Teddy, ages 5 and 3, as nascent sentient beings, and to see what stuck. What did we want them to remember? That we weren't afraid to go. That we sought out the world on the map on their bedroom wall and brought it to life, in all the vivid, surprising, messy ways that life comes.

We kept a family trip journal as one way to see what stuck. Each person contributed a highlight and lowlight from each day, along with at least one new thing. The chickens and coconuts made it into Day One (Teddy: new thing). The 4 a.m. rooster concert made it into Day 2 (Matt: lowlight).

The boys, though, slept right through the show. Back home, one of the things I despise most is my weekday role as the household alarm clock: Wake up, get dressed, go to the bathroom, wash your hands, brush your teeth, eat breakfast, we'll be late for school, I have to get to work, hurryuphurryuphurryup. I longed for the expansiveness of waking up at our leisure - to wake up whenever we woke up, to go back to sleep when needed. In Hawaii, I wore earplugs. To me, those chickens signified a kind of liberation.

Kuai

The boys called it "our world trip." It started last spring with a countdown on the refrigerator, each calendar square carefully x-ed out in black marker by our older son, Felix. Every morning, he sighed.

"I wish we were going on our world trip today," he'd say, grumbling into his bowl of cereal. His eagerness to leave the everyday startled and excited me, in equal parts. One day, there were no more boxes to cross off.

We mapped our route with places we knew and loved (Hawaii, Italy) and those we knew not at all (the island of Hokkaido in Japan, Norway), alternating laid-back destinations with more challenging travel. Our children were young, after all, and we wanted it to be fun. We booked around-the- world tickets and stayed mostly in lodgings we found on Airbnb, interspersed with the odd campsite, hostel, hot-springs resort, and airport hotel-and one week spent volcano-hopping, driving around the res- tive, remote island of Hokkaido in an RV. Each spot and its sensory details embodied some larger idea about place and culture.

In Hawaii, our initial goal was decompression from that habitual hurry-up-and-go routine. Matt, who runs an environmental consulting rm in San Francisco and had finally granted himself a break, was especially happy to avoid the commute. We started with three weeks in a house just big enough to accommodate a rotating cast of visiting family and old friends who now lived on Oahu. Three weeks, it turned out, was just the right amount of time for remembering how to relax. The boys spent hours in the ocean at Tunnels Beach, where a wide, shallow reef kept them safe, and marine fauna-baby parrot sh, big green sea turtles, even a spotted eagle ray-kept them entertained. They learned to identify humuhumunukunukuapua'a, Hawaii's state fish, and how to pronounce the name with confidence. There were long walks to and from the beach, Felix and Teddy skipping and chatty. There were naps on the couch. Days without e-mail. Surfing daily. There was time to wander and wonder. One day Felix asked me how babies are made. So I drew him a diagram in our journal. (This trip was also about challenging ourselves, after all.)

There were rainy-day dance parties and rainy-day doldrums. There was the day Teddy screamed with joy at a rainbow.

And there were the many other days he screamed with tantrums - memorably, agonizingly, in the slow-crawl customs line upon arrival in Japan.

Japan

Mostly, though, the boys rolled with it, and so did we. We crossed the international date line together. In Japan, they greeted strangers with a pleasant konnichiwa and remembered to say arigatō. During our first few days acclimatizing at a tiny garden house on the edge of pristine Lake Toya, we admired the six different drain filtration nets in the kitchen sink and the numerous recycling systems, all part of detailed efforts to manage waste and runoff into the lake. The Japanese take meticulous care of their nature areas. In contrast to Kauai, the nights in that remote locale were vacuum quiet. Matt's sleep was blessedly sound.

On Hokkaido, the northernmost island of Japan, there was the strangeness of natural-disaster tourism. Historic videos atop the Mount Usu tramway detailed the risk of volcanic apocalypse (and Mount Usu's most recent eruption, in March 2000). But we took the chance on lengthy hikes both there and at Mount Asahi in Daisetsuzan National Park because - well, no risk, no reward, right? We ended up half carrying said boys, but the sweaty 30 to 40 pounds on our backs were worth the climb to exhilarating 360-degree views of steaming calderas and dramatic ridge- lines around the top of Mount Usu (summit: 2,405 feet). On snowy, fog-shrouded Mount Asahi (summit: 7,516 feet), we coaxed Teddy and Felix up steep boul dered paths, and they earned the praise of Japanese hikers on the trail. ("Genki!" the hikers would say, waving their trek- king poles and admiring the boys' vigor and stick-to-itiveness.)

Over two weeks, we became acquainted with Japan's wild, rugged natural character. We camped with Japanese friends at jewel-like lakes, soaked in steaming onsen - hot springs, naturally heated by thermal vents underground-and stopped to eat fresh-caught sushi and locally grown produce. Every farming town had a little mascot: a dancing apple, say, or a grinning mushroom. We drove past rows and rows of rice fields that hypnotized me with their damp and flickering light.

Italy

In northern Italy, the tiny lakeside hamlet of Orta San Giulio was beloved to us already - we'd stumbled upon it five years earlier and became enamored of its slow-paced and neighborly small-town living - but now we had the third-floor patio of a 16th-century apartment from which to view its particular streetscape alfresco. Donatella, the second mayor of Miasino, just uphill from Orta, came to show us in with her 8-year-old son, Bruno, who proceeded to race around the spiral stair- case with our boys. Across the street was a 500-year-old wine bar we loved from our previous visits. It was there we'd gotten to know our Italian friends Virginie and Riccardo, who run a gelateria in town; they were eager for our return so they could try out their new ice-cream flavors on us.

Every morning for a week, I swam in Lake Orta from the cobblestoned alley in front of the apartment's balcony.

In the main pedestrian piazza, we found signora Irene, who remembered how Matt and I had swum to and from the lake's island monastery four years before. We celebrated Felix's sixth birthday with pizza, gelato, and chocolate cake. Survival parenting here often looked like a pile of pas- tries. During our second week in Orta, my mother and her three sisters arrived from their Grand Tour of Italy. We'd encouraged them to see Rome, Florence, Venice, and more before coming to Orta to spend time with us. That first night, I took them to an evening classical music concert in the town's historic church. The next day, Alessandra at the café told me with a smile that I had "una faccia nuova" - a fresh new face, from having a night off from the children.

In the lovely palazzo we rented for my mom and aunts, I pulled my first espresso from the house machine in the kitchen. There were glorious views of the lake and hordes of mosquitoes at night. Extended-family living meant that Teddy's and Felix's in-country highlights included regular trips to get gelato with their grandmother and great-aunts. Teddy played with Melissa, the daughter of the toy-store owner, in the piazza. Felix played Monopoli with euros and learned that Parco della Vittoria was the Italian equivalent of Boardwalk.

On our last day in Orta, Day 49 of our world trip, we visited with our friends at the gelateria. At the barbershop next door, the boys received the most fashionable haircuts of their young lives, courtesy of Ruben. Then we drove the hour and a half to Milan and flew to Oslo.

Norway

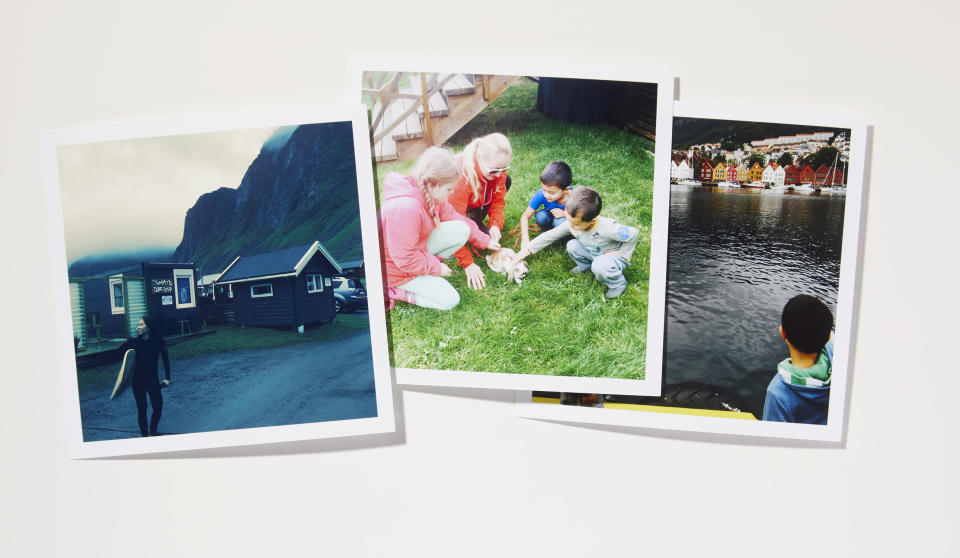

Norway in summer is a magical, other-worldly place of 24-hour daylight - it filtered into each house and bestowed its own character. It crept under doors and around blinds. It made midnight seem like party time. The boys started going to bed at 10 and getting up at 10. Happily, there was nowhere to be but right where they were. And right then they were actively being in the world they were so accustomed to seeing as coming to them, in books and movies, stories and maps. Along the lovely sun-kissed shores of the fjords, they discovered that the Norwegian family who rented the house to us had pet bunnies-far and away Felix's favorite animal. They pretended to be Arctic explorers at the maritime museum and tried with all their might to pull a sled. At a mountaintop in Bergen, they roamed trails overlooking the fjords.

Spending 24-7 with your young family is euphoric and maddening at the same time. I think this is the point in the trip when I started to think about mortality. Before you start to wonder what went so terribly wrong, let me tell you that nothing did. Having time to think, though, means you have time to register the note of bittersweetness in everything - the food, the fun, the fights - with the appreciation that it's all fleeting. Even the fat starfish hand of your child as he falls asleep.

Many nights at home I wake with a start. The circumstances of this recurring dream change subtly from one version to the next. But I always have the same thought: I need more time.

On this trip I didn't have that dream.

Like what you see? Enter to win a $5,000 Airbnb credit. Want more? Get your free issue of Airbnbmag.

You Might Also Like