'I was shaking': D-Day battle still fresh for surviving veterans 75 years later

OMAHA BEACH, France – Except for the syncopated squawking of gulls and the rhythmic ebb and flow of waves, the beach is quiet now.

There are no rat-tat-tat bursts of machine gun fire from the bluffs. No desperate screams from the wounded crawling through the shallow surf. No sergeants shouting to "keep moving."

Seventy-five years later, Omaha Beach, the blood-soaked centerpiece of the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, that broke Adolf Hitler's grip on Western Europe, now resembles countless other beaches around the world. It's a place to relax.

On a recent afternoon, a young woman rode a horse along the water at low tide, past L'Omaha Restaurant and a line of cottages overlooking the English Channel. A man jogged in the opposite direction, heading toward a narrow road that led up the bluffs to the Omaha Beach Golf Course and the Omaha Beach Spa. A young girl dropped to her knees, laughing as she tossed handfuls of sand into the brisk wind.

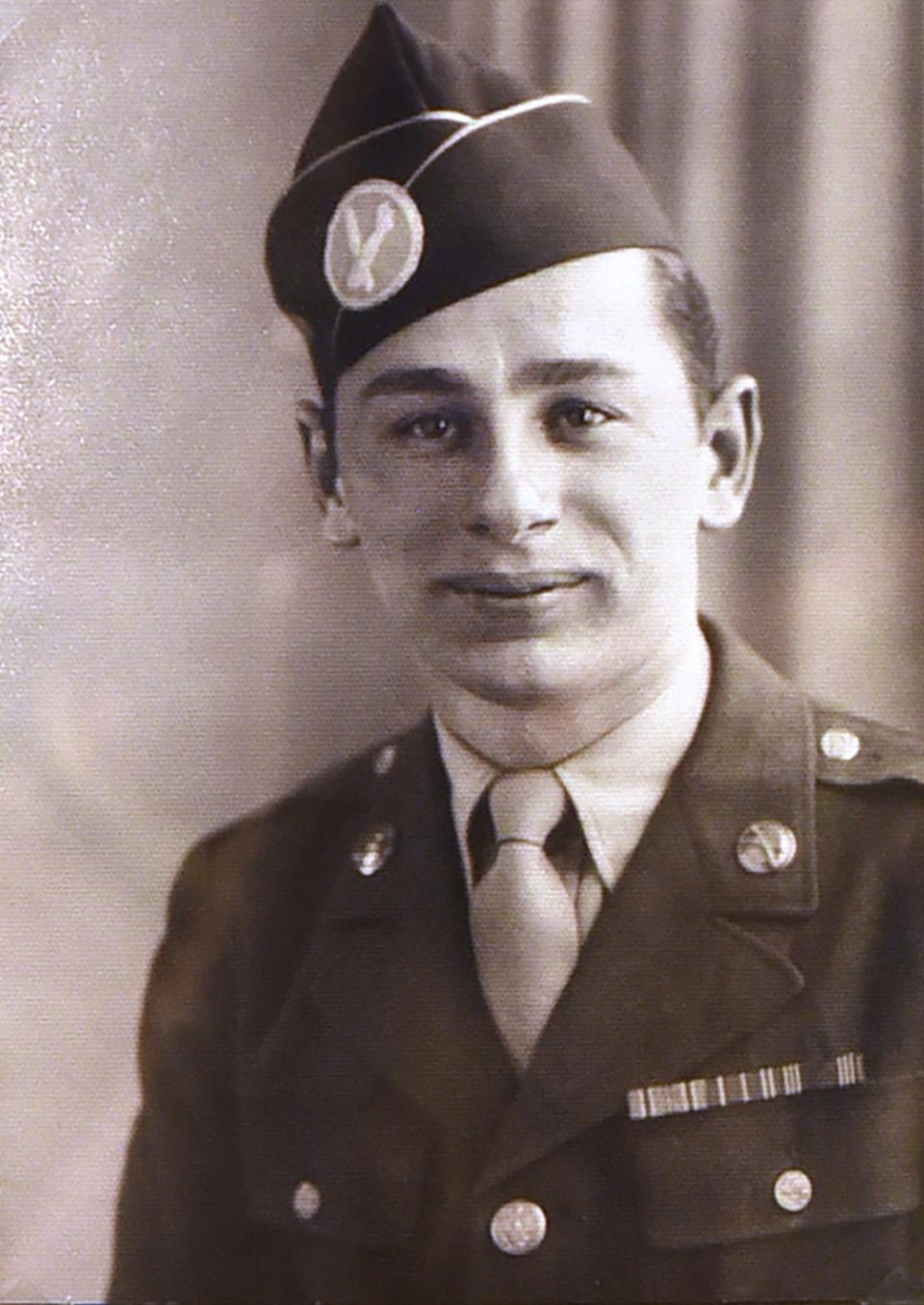

Days later and more than 3,500 miles across the Atlantic Ocean, John Santillo settled into a chair in the living room of his home in Brick Township, New Jersey, and recalled a far different scene on the Normandy coast 75 years ago.

Santillo is 97 now, a gregarious man who still drives a car and has an infectious laugh. But that cheer disappears and his voice softens as he thinks back to the morning of June 6, 1944, when he bounced through the choppy surf off Omaha Beach in a landing craft with fellow soldiers from the Army's 237th Combat Engineer Battalion.

Santillo was just 22 then, a self-described cocky kid from Newark's Ironbound. But as he gazed over the gunwale that morning and took in the shocking carnage at what would be nicknamed "Bloody Omaha," Santillo felt his street-smart bravado evaporate.

Minutes later, he felt strangely lucky.

With the intense fighting on Omaha Beach backing up successive waves of landing boats, Santillo's team of engineers was suddenly diverted to a somewhat safer spot several miles westward at another American landing zone, code-named Utah Beach.

"Don't think I wasn't scared. I was shaking," Santillo said, pausing for a moment and then adding: "If I went to Omaha, I would have been killed. You don't know what's going to happen. You wonder if that shell has a name on it."

The cost of survival

War is not just about guns and battles and solemn ceremonies in the years that follow. It is also about the personal memories of soldiers' sacrifices and the emotional cost of surviving and then trying to bear witness to what you saw.

But as the world commemorates the 75th anniversary of the Normandy invasion — D-Day, as it is termed by many — that memory is fading. Historians estimate that only 500,000 of the more than 16 million Americans who served during World War II are still living. Fewer than 1,000 D-Day veterans are believed to be alive, according to the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

"With the passing of the World War II generation, your average American has fewer and fewer connections to World War II," said Steve Waddell, a professor of military history at West Point Military Academy. "But if Americans remember anything about World War II these days, it's Pearl Harbor, D-Day, the flag raising at Iwo Jima and the atomic bomb."

On June 6, President Donald Trump and leaders from France, Canada, Great Britain and other allies who fought against Nazi Germany plan to gather for a variety of ceremonies along the 50-mile stretch of Normandy coastline where more than 150,000 troops came ashore in what was the largest amphibious landing in history.

John Santillo plans to be there, too — he will return to France with a group of Florida-based veterans.

For Santillo, it will be his first trip to France since he plunged ashore on that wind-swept, chilly June morning in 1944. He said he wants to walk along the now-peaceful Omaha sands, then visit the cemetery on the bluffs above the beach where nearly 10,000 American soldiers who died on D-Day and in the ensuing two-month battle of Normandy are now buried.

"I have to go to the cemetery," Santillo said, pausing before adding: "I'll probably get a little choked up at all the poor guys we lost. That was a rough day."

Nearly a disaster

The invasion, code-named "Operation Overlord" but known by many today as "D-Day," nearly turned out to be a massive and embarrassing disaster.

After assembling an attack force of more than 150,000 soldiers from the U.S., Great Britain and Canada, along with 50,000 vehicles, 11,000 planes and 6,000 ships and landing craft, many of D-Day’s first waves landed in the wrong places along a 50-mile stretch of Normandy's coast. Some units were unable to communicate with each other for hours.

Thousands of airborne soldiers who parachuted into the darkness of Normandy's countryside hours earlier were blown off course in high winds. Some drowned when they dropped into low-lying fields that had been flooded by the Germans.

As if that were not bad enough, German defenses rained a non-stop torrent of bullets on the troops as they waded through waist-high surf on the beaches and then across hundreds of yards of open sand.

Other units never even made it to the beaches. Their landing crafts either sank in the stormy surf or were blown apart by submerged mines and German artillery.

Casualties were staggering. More than 12,000 soldiers from the U.S., Great Britain and Canada were killed, wounded or declared missing by the end of D-Day — nearly 8% of the invasion force.

The most deadly spot was the 5-mile stretch of sand near the petite French farming villages of Colleville-sur-Mer and Vierville-sur-Mer. Its code name: Omaha Beach.

Nearly 1,500 U.S. soldiers were killed during the first hours at Omaha, with another 3,000 wounded or missing — so many that the surf turned red from the soldiers' blood, observers said.

Only a dozen of the 200 soldiers in a company-sized unit from Bedford, Virginia — all National Guard volunteers — survived the first minutes on Omaha Beach, according to an account by historian Stephen Ambrose.

Other units in the first waves on Omaha lost as many as 60% of their soldiers. Scores of burning tanks and crumpled trucks and jeeps littered the sand. As other waves of troops came ashore, they had to step over the bodies of dead soldiers floating in the surf.

"All along the crescent shaped strip of beach, dead Americans gently nudged each other in the water," wrote Cornelius Ryan, a Dublin-born war correspondent who covered the D-Day landings and went on to write "The Longest Day," a widely acclaimed 1959 account of the battle.

By nightfall, Omaha and the other four landing beaches — code-named Sword, Juno, Gold, and Utah — had been secured. Within a week, more than a million Allied soldiers had landed, with more than 75% of the U.S. units having passed through Camp Shanks in Rockland County, New York, on their way to ships for their journey to France. Eventually, more than 3.2 million Allied soldiers would pass through Normandy on the way to battles across northern Europe.

The D-Day successes did not end the war — far from it. Brutal fighting continued through France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Austria and Germany into 1945. But D-Day gave the Allies a clear upper hand against the Nazis. Within three months, Paris was liberated. Less than a year later, Germany surrendered.

Enduring importance

Why D-Day continues to hold such an esteemed place in U.S. history is obviously due to its strategic importance to the overall war effort against the Nazis.

Had the Allied landings failed, historians say, the Nazis would have likely strengthened their hold on Europe, lengthening the war for at least another two years. As a result, millions more Jews and others would probably have been murdered in Nazi concentration camps, and Soviet forces might have seized greater swaths of Germany and perhaps even France and other European nations at the outset of the Cold War.

“That would have translated into a very different 21st-century world,” said Keith Huxen, senior director of research and history at the National World War II Museum.

“The invasion of Normandy had to succeed. It was one fantastic gamble,” Huxen added. “There was no Plan B.”

Yet another factor in establishing D-Day’s place in history was the sheer number of journalists who converged on the invasion to chronicle the exploits of the troops.

Besides Cornelius Ryan, there was Ernie Pyle, Walter Cronkite, Andy Rooney, Robert Capa, A.J. Liebling, Martha Gellhorn and her husband at the time, Ernest Hemingway. In recent decades, the D-Day story gained even more traction with younger generations through such films as “Saving Private Ryan” in 1998 and with the 2001 HBO series “Band of Brothers.”

Flint Whitlock, the editor of Virginia-based World War II Quarterly magazine, describes D-Day now as “the French version of Gettysburg.”

“It was such a heroic operation,” Whitlock said. “It was something that we in the West — America and Great Britain — generally regard as the finest hour of our country’s contributions to World War II. It was one of the few — and perhaps last — times that our country was on the moral high ground, and D-Day was the epitome of stamping out evil for the good of all humanity.”

Whitlock, who is leading a tour of the Normandy battlefields this week, said he has developed a deeper understanding of the soldiers' sacrifices and the brutality they faced by exploring the beach at Omaha and other landing sites and then climbing the bluffs where the Germans weaved together a deadly maze of machine gun nests and artillery batteries.

“In order to understand the battle you have to walk the battlefield,” Whitlock said. “You can read books. But it takes being there on the ground to understand what the soldiers were confronted with.”

"It’s like a religious experience to stand there now," added West Point's Steve Waddell.

On a recent afternoon, Anne-Marie Leblic, a French-born battlefield guide, led a group of mostly American tourists to the Omaha sands.

It was low tide when the group’s bus rolled down a narrow road from the tiny farm village of Vierville-sur-Mer and through a narrow canyon in the Omaha Beach bluffs that was still dotted with German bunkers. The bus stopped on the edge of the flat beach, nearly 300 yards wide — the same open terrain that confronted U.S. forces when they stormed ashore 75 years ago at low tide as German guns on the bluffs targeted them.

In moments like this, Leblic said, she often thinks back to her father, Arthur, a French soldier who had been taken prisoner by the Nazis in 1940 and was forced to work in a German factory that had been confiscated from its Jewish owners. In 1945, Arthur Leblic was freed by the same Allied forces who landed at Normandy.

Now 69, Anne-Marie Leblic routinely makes the two-hour trek to the beaches from her home near Rouen, France. She sees herself as far more than just an ordinary tour guide, but as a keeper of her father's memory.

“The veterans are disappearing,” she said. “You have a full generation of French people who have no connection to the war. It’s necessary to maintain the memory.”

Besides walking on the beach, Leblic's tour group visited the American cemetery atop the Omaha Beach bluffs, where row after row of crosses and Stars of David mark the final resting places of nearly 10,000 U.S. soldiers who were killed in the D-Day invasion or during the subsequent two-month battle of Normandy.

Among them is the grave of Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt Jr., who was awarded a Medal of Honor after volunteering to lead the first wave of troops ashore at Utah Beach. Roosevelt, 56, the son of President Theodore Roosevelt and a cousin of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, suffered a fatal heart attack a month after the D-Day landings while fighting elsewhere in Normandy.

As Leblic's group entered the cemetery, it paused by the 22-foot bronze statue of a U.S. soldier by sculptor Donald De Lue, titled "The Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves."

It was early afternoon, and the cemetery's bells began to play the national anthem. Slowly, their voices rising with each stanza, the group began to sing.

Standing in the crowd, Greg Shaughnessy, 72, a retired advertising executive from San Diego, found himself thinking of what the soldiers landing on the beach below the bluffs experienced three-quarters of a century ago as they charged through the hailstorm of enemy fire.

"In a sense, it evoked in me a renewal of my deep-seated love of country," Shaughnessy said afterward. "It was a sensation that I will cherish the remainder of my days."

Remembering those lost

Back in New Jersey, at his home in a retirement community in Brick Township, New Jersey, Daniel Passarella said a day rarely passes when he does not think about D-Day and the friends he lost.

Passarella, 96, was born in Chicago and had been assigned to the 101st Airborne Division in 1944. Instead of parachuting into Normandy, his unit was ordered to board wooden gliders that would be towed across the English Channel by larger planes, then released to float downward and land on Normandy’s farm fields.

At the last minute, however, Passarella was ordered to board a ship for the trip to Normandy. He says the Army told him it did not have enough planes to tow all the gliders.

So the next morning, Passarella found himself wading ashore at Utah Beach.

After the war, Passarella rarely spoke about his experiences. But a decade ago, when his granddaughter, Sarah, said she was writing a report on World War II, he opened up.

"From that day on, we started learning more," said one of Passarella's daughters, Carole Marmion, 70, of Toms River.

"I never thought about my dad as being a veteran until he became a grandparent," added another daughter, Donna Bonomo, 62, of Southport, North Carolina. "He was always just a businessman."

"My kids never knew anything about me in the war," said Passarella.

Like many veterans, Passarella tried to move on with life after he returned to America. He got married, settled in Wyckoff, New Jersey, embarked on a career with a food-supply company and devoted most of his free time to raising three daughters and three sons.

Looking back now, Passarella reasoned that he kept quiet about the war because the memories of what he endured were too painful. As he fought his way across Utah Beach and then into the hedgerows and farms of Normandy, he said, he was haunted by a question: "How long is it going to be before I'm laid down?"

The answer came less than two weeks after the D-Day landings.

Passarella’s unit was patrolling the small Normandy town of Carentan. A German bomb exploded. Pieces of shrapnel shredded Passarella's back, and he was evacuated to Great Britain, where he battled infections for months before finally returning to America.

Passarella never spoke to his family about his wounds until decades later when he told his granddaughter, Sarah. Passarella’s story spread through his family and beyond. And in 2012, at the urging of his congressman, Rep. Chris Smith, the Ocean County, New Jersey, Republican, the Pentagon finally gave Passarella a Purple Heart.

"I don't want to be a hero. I was just an ordinary soldier," Passarella said on a recent afternoon at his home, as he leafed through a scrapbook that included a photograph of him and other 101st Airborne soldiers during a pre-invasion inspection at their base in England by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander.

On June 6, Passarella plans to board a bus in New Jersey before dawn for a trip to Washington, D.C., with other World War II veterans to attend ceremonies commemorating the 75th anniversary of the Normandy invasion.

His legs are not as strong as they were when he fought with the 101st Airborne. He navigates now with the use of a walker. But he still dreams of returning to Normandy and finally strolling across the once-lethal beaches and fields without fearing he might die.

"I'm going back someday," Passarella said with a smile. "I'd like to go back when I'm walking."

Mike Kelly is a columnist for The (Bergen) Record of New Jersey, where this column first appeared. You can follow him on Twitter: @MikeKellyColumn.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on North Jersey Record: 'I was shaking': D-Day battle still fresh for surviving veterans 75 years later