'A Country Within a Country': Inside the Navajo Nation in 1948

As LIFE described the situation to readers in 1948, the Navajo Nation was “a country within a country” — a reminder that Native American history courses inextricably alongside everything else that falls under the umbrella of American history, a fact that is underscored for Native American Heritage Day on Friday.

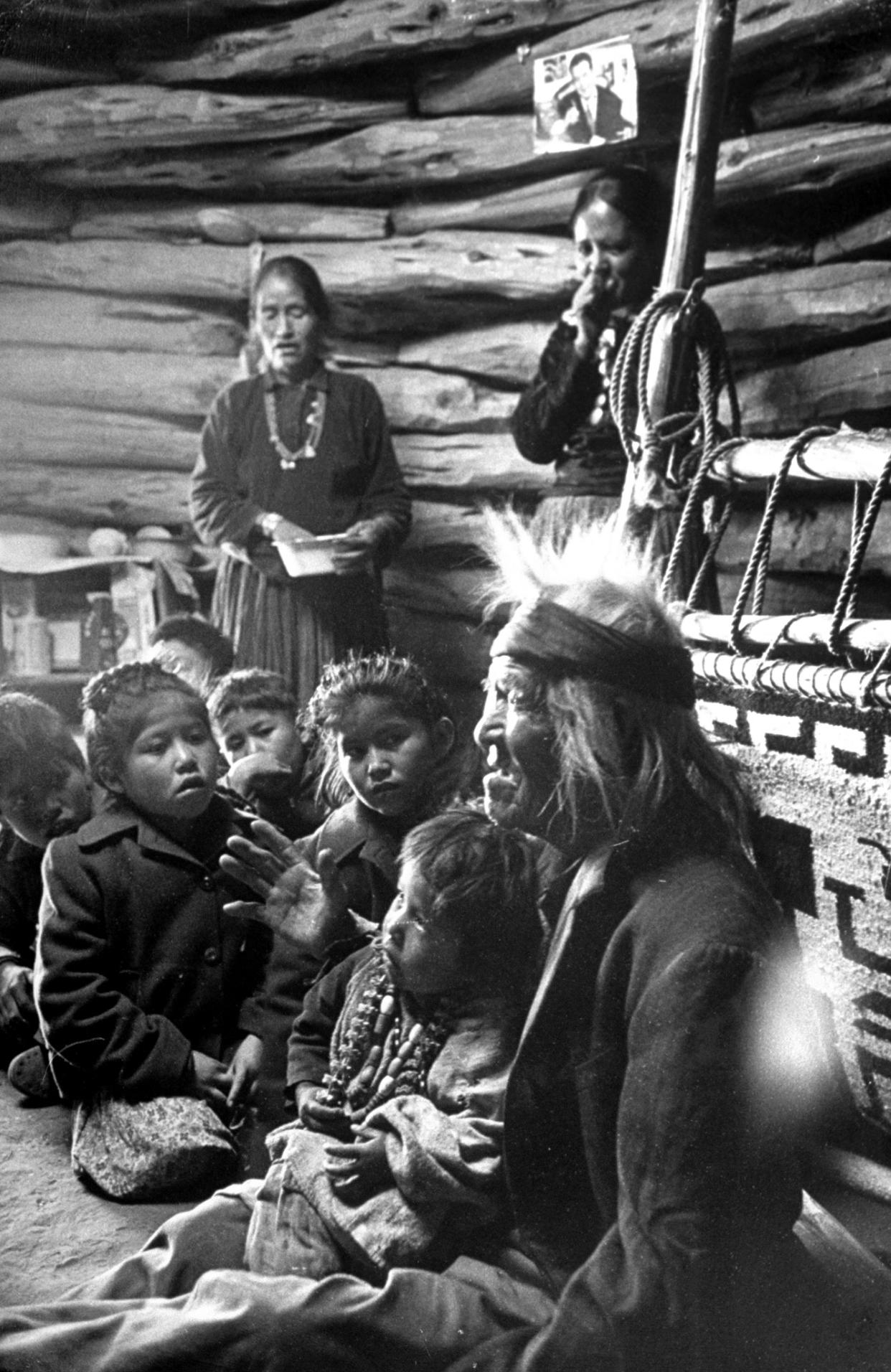

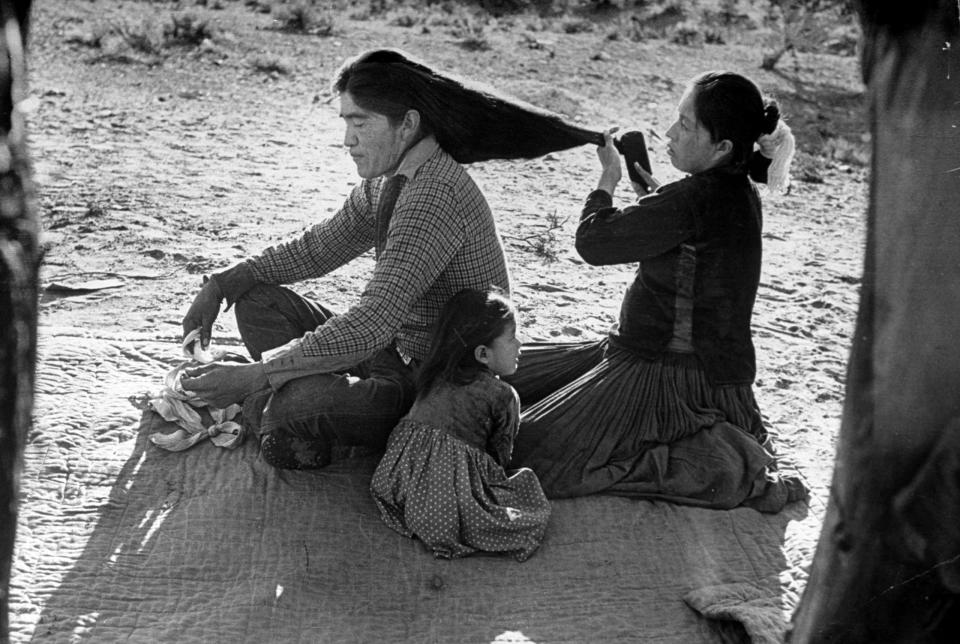

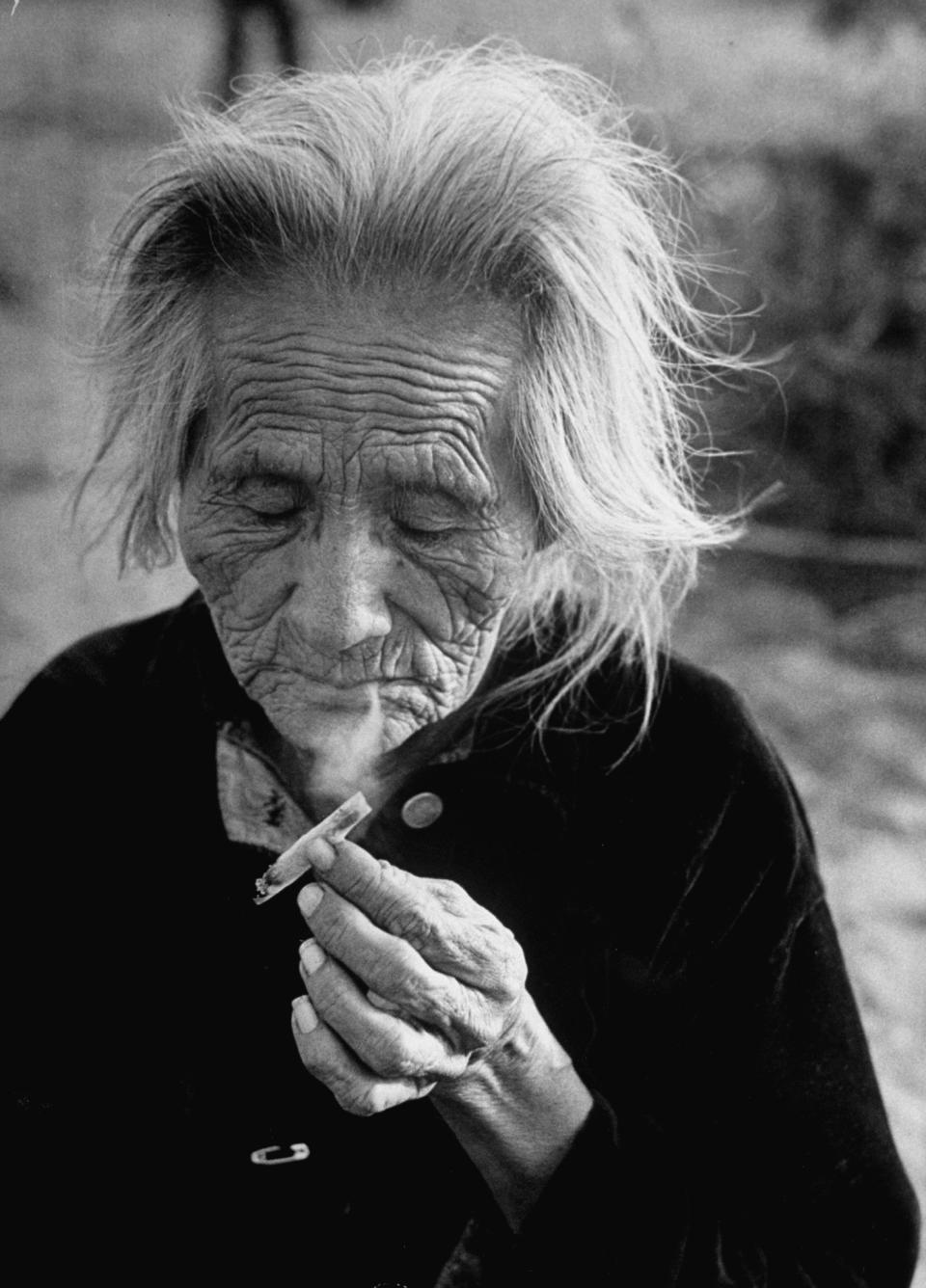

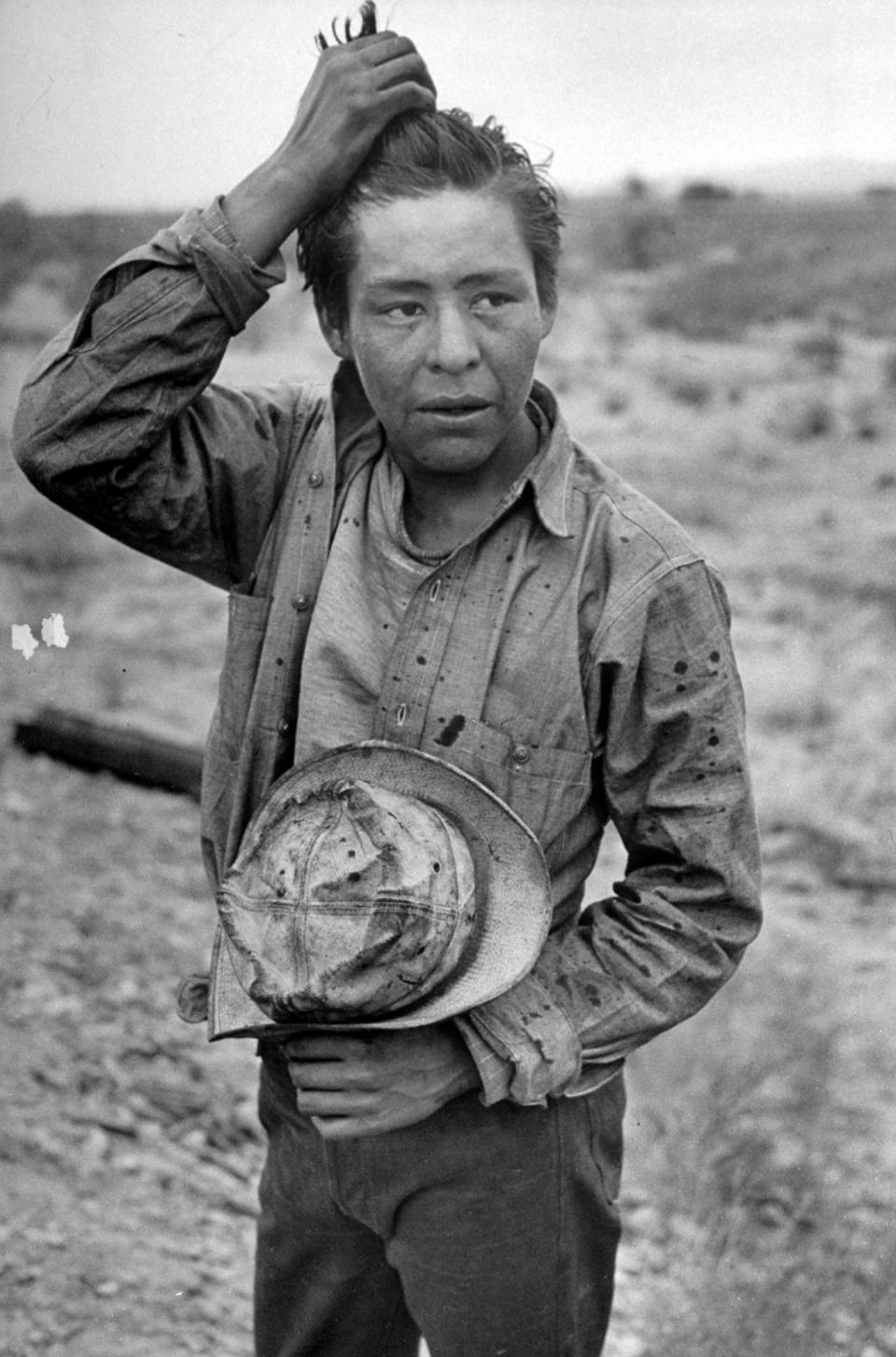

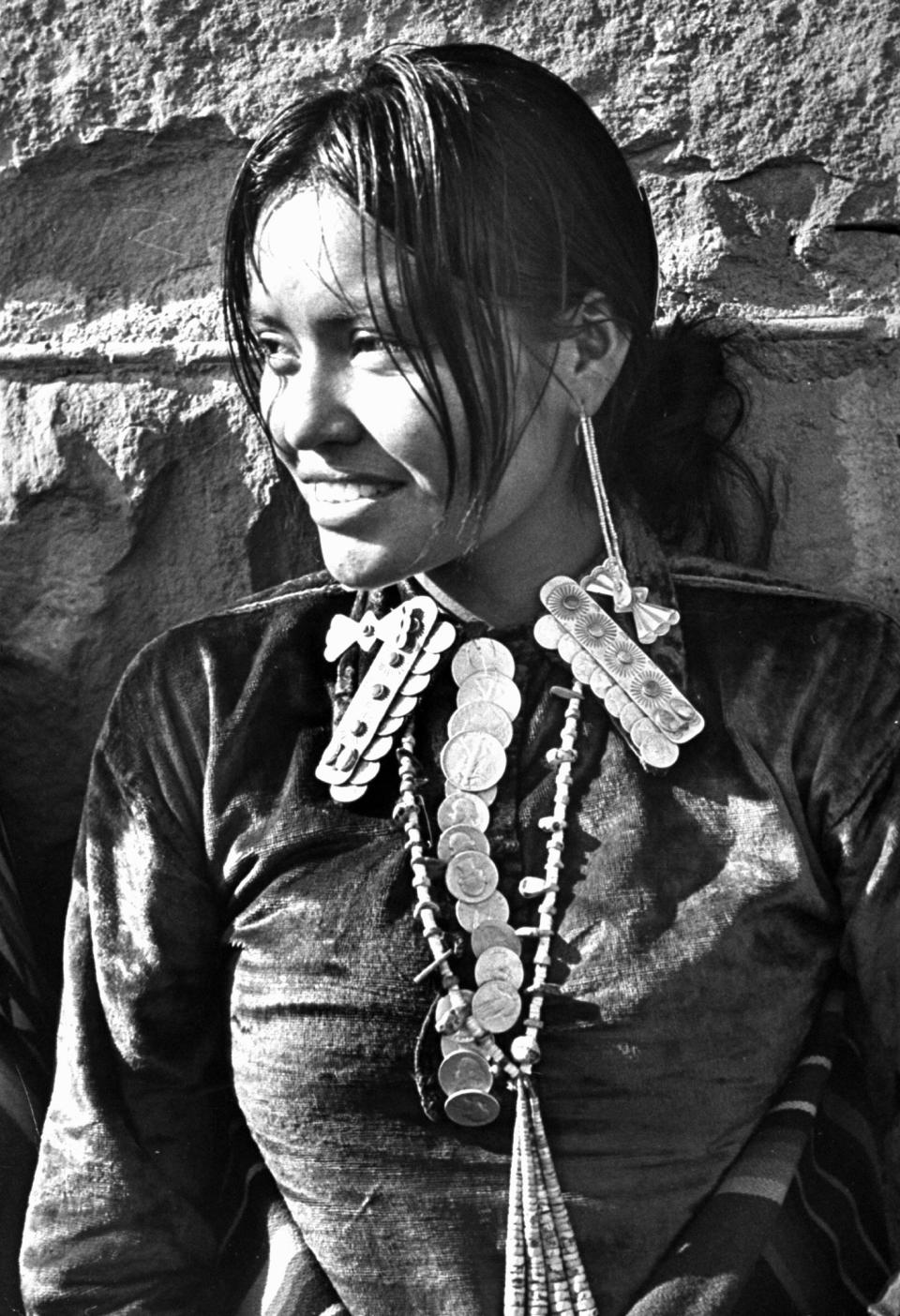

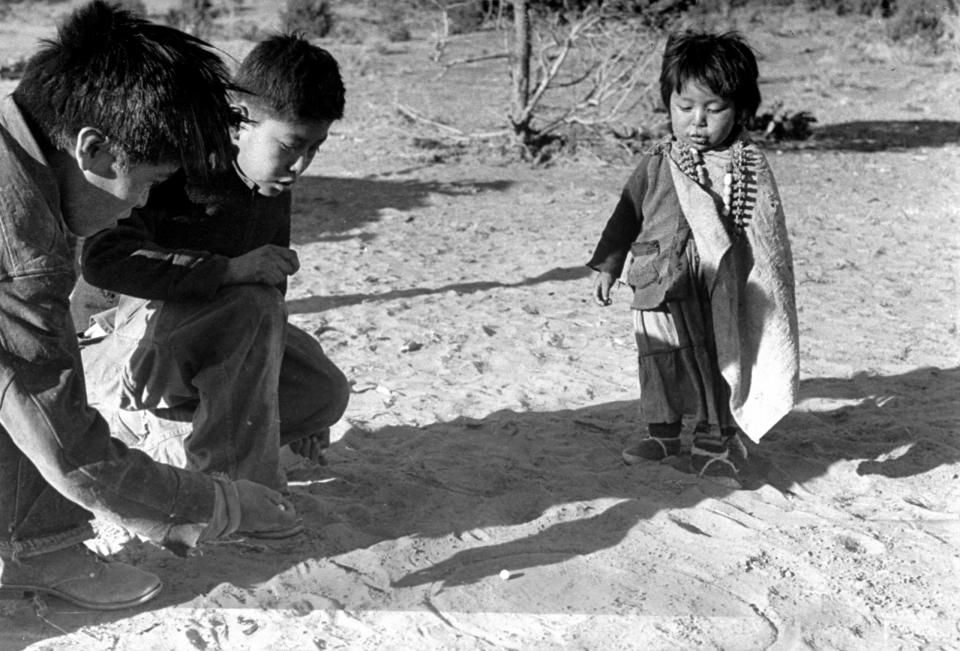

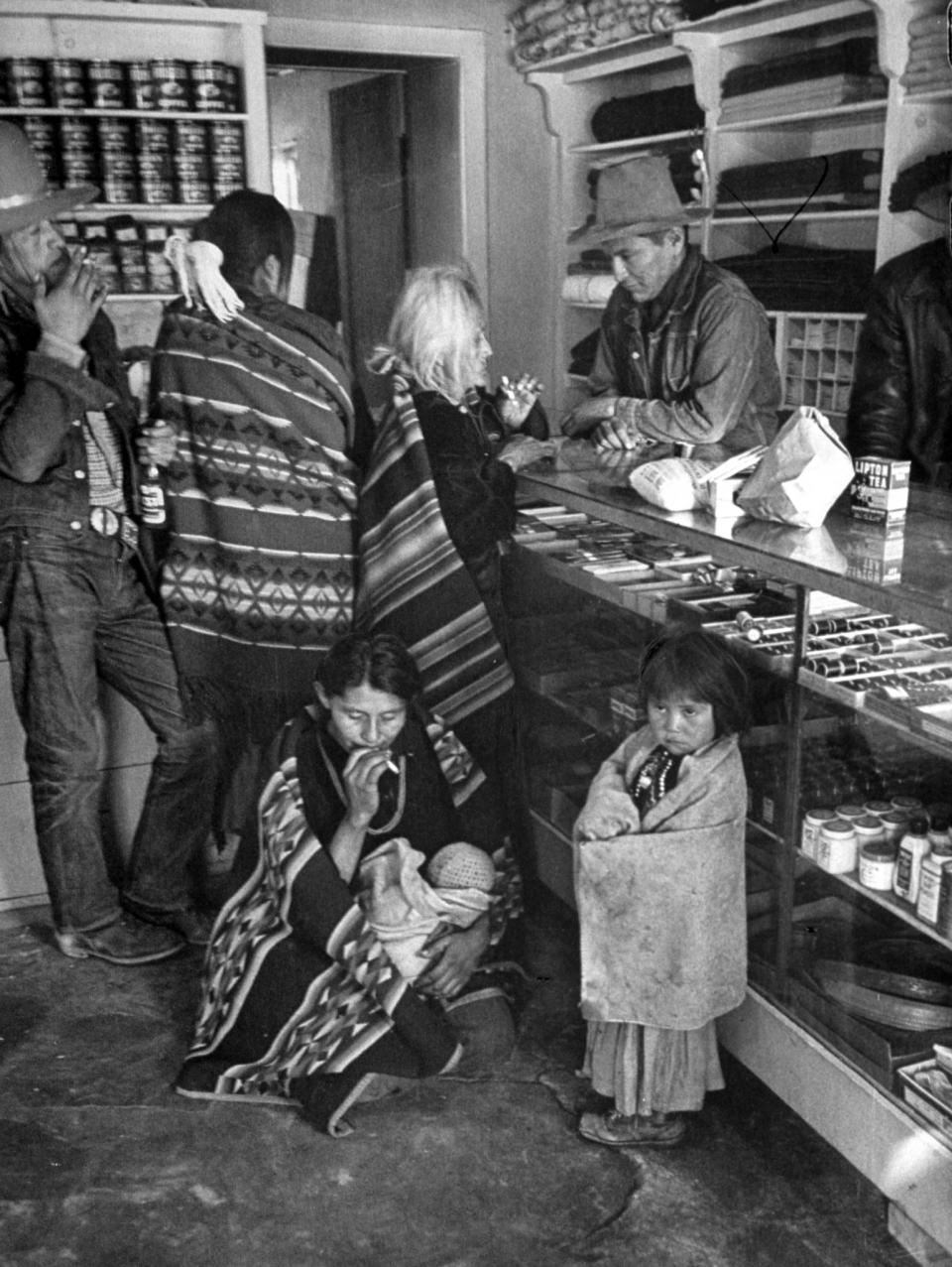

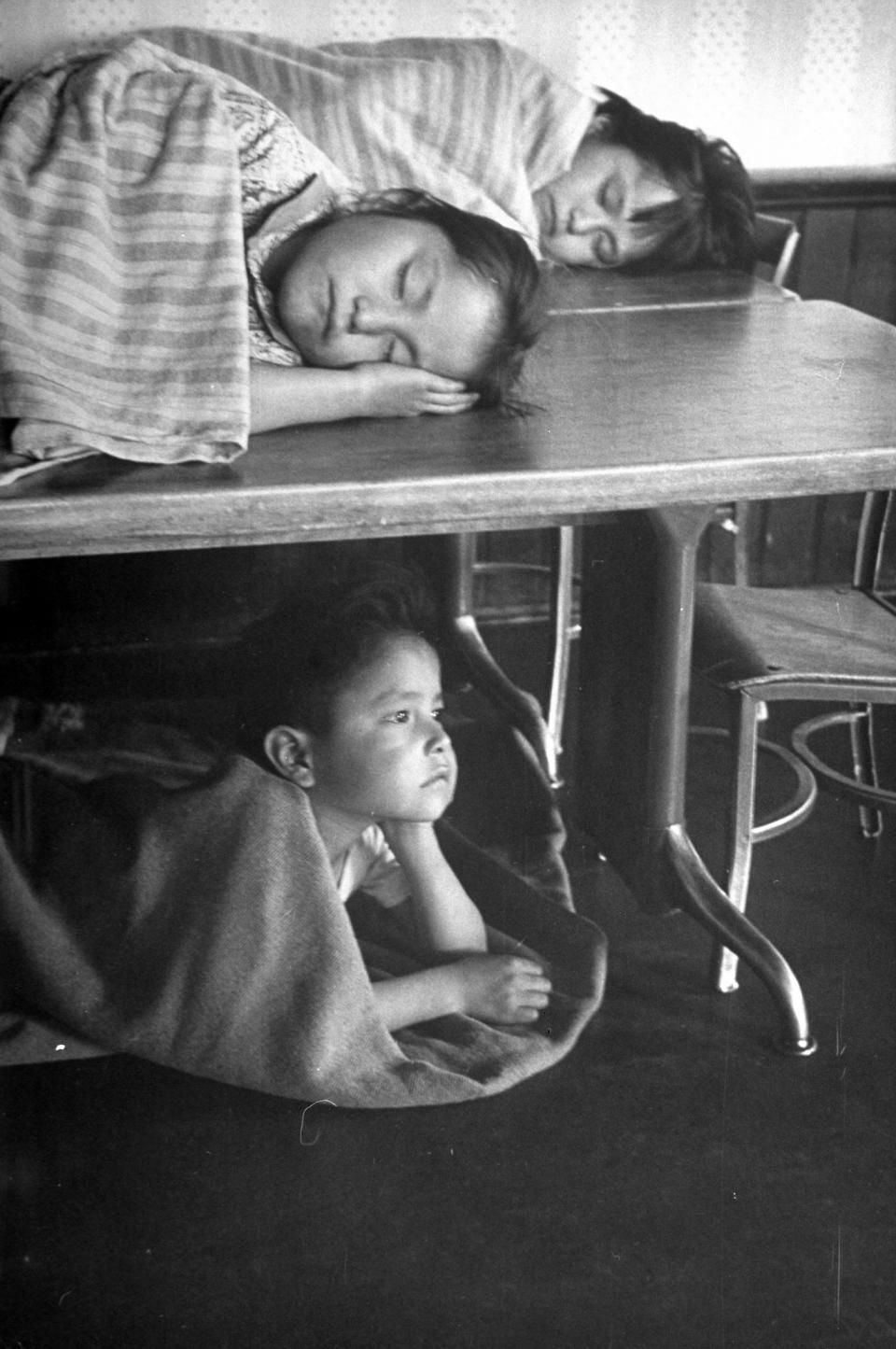

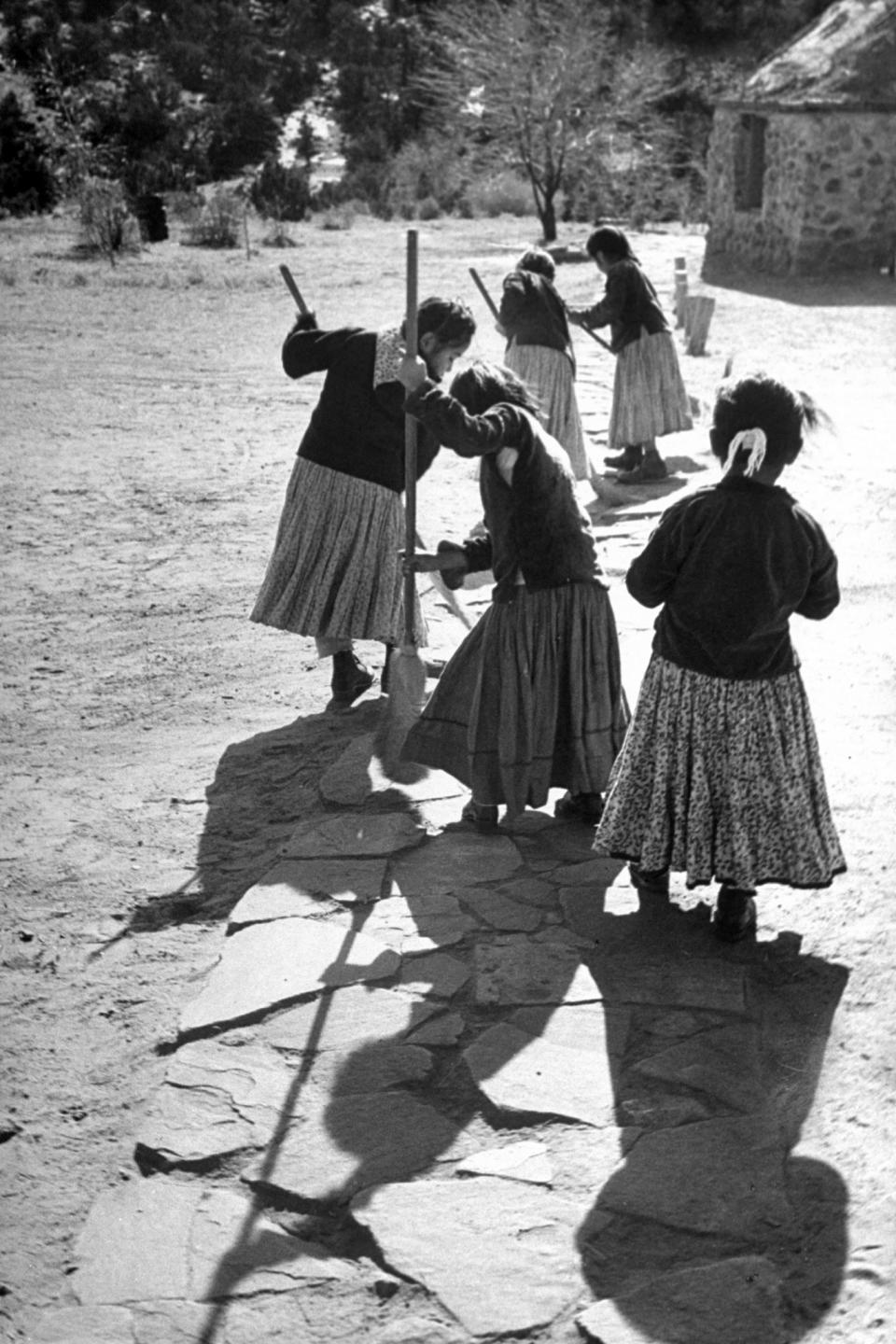

When photographer Leonard McCombe visited Navajo country in Arizona to create the images seen above, however, he caught a people at a very specific and important point in that long and ongoing history. The Navajo Nation, which comprised about 61,000 members at the time and was the fastest-growing Native American group in the nation, was at a moment of crisis.

By that point in 1948, the U.S. government was well aware that the land on which the Navajos lived could no longer support the residents, but that fact was news to most Americans, who first heard the story through news reports of starvation on the reservation. However, as LIFE noted, simply sending food wouldn’t solve the problem.

The story focused on the extended Yellowsalt family, most of whom made their living by herding sheep. The family couldn’t get permission from reservation administrators — who pointed to the disappearing grass in the area — to expand the flock. By the government’s calculations, according to LIFE, the land could only support enough sheep for about 20% of the families to own enough of the animals to make a sustainable living, or for more families to barely scrape by. Meanwhile, even though exposure to white populations had introduced new and devastating diseases into the Navajo community, the government-run hospitals didn’t have enough beds to support the population.

The two central questions posed by the story were inescapable: “How can technical knowledge be made available to a primitive people without destroying the whole fabric of their lives? How can nations which differ from each other in appearance and language and culture live peaceably together?”

Now, nearly seven decades later, replace the word “primitive” with “native” and those questions are still profound ones, says David E. Wilkins, a professor of American Indian Studies at the University of Minnesota and an author of The Navajo Political Experience.

“Overall, I was surprised at the general accuracy of the piece,” Wilkins tells LIFE, considering the date and the audience for which it was written. “It was full of the assimilation language that was dominant at the time, but that wasn’t surprising.”

Wilkins has some other quibbles with the story — for example, LIFE published images of bare-breasted Navajo women that strike him as strange, as he says he’s not aware of a ceremony in which Navajo women would usually go unadorned — but the big thing that’s missing, he says, is a sense of the larger context in which the Yellowsalt family was living. LIFE hints at the reasons why there aren’t enough sheep for the family to prosper, noting that when the people returned to land they’d been forced from in the late 1800s, it was now a reservation “hemmed in by land-hungry whites,” and that grazing flocks on that fenced-in space destroyed the range. “As the Navajo nation grew,” LIFE noted, “the land, the basis of its existence, began to fail.” But as Wilkins points out, it was a federal livestock-reduction program in the 1930s — not the natural course of things — that had mandated they cut back on grazing animals on that land.

“In 1948, the Navajo Nation was still reeling from the livestock-reduction program,” he says. “It devastated the Navajos economically, psychically and culturally.”

The coming of World War II staved off economic disaster for a little while; Wilkins says that over 15,000 Navajos were employed in some fashion as a result of the war. But in 1948 the consequences could no longer be denied. “The war’s over and they go back to the reservation and there’s nothing there because of wrong-headed policy makers who thought they were doing the right thing,” he explains. Though those policy-makers thought they saving the land from overgrazing, Wilkins says that in fact later research shows that the Navajo livestock were not a primary cause of the problems. In addition, though federal policy affected every aspect of Navajo life, it was only later in 1948 that the Arizona Supreme Court declared that the state’s Navajo citizens had the right to vote.

But the best thing about this article, Wilkins says, is what happened after it was published.

Media attention paid to the crisis among the Navajo People, with popular journalistic reports such as this one, contributed to what Congress did in 1950. That attention, Wilkins says, encouraged them to pass the Navajo-Hopi Long Range Rehabilitation Act, which “helped to save those two peoples from the economically crippled situation they were in.”

Assistance like that — coming from the very source that had contributed to the problem in the first place — made a huge difference for those tribes in the 1950s, and is perhaps an example of one part of an answer to that central question: How can two very different nations live peaceably together?