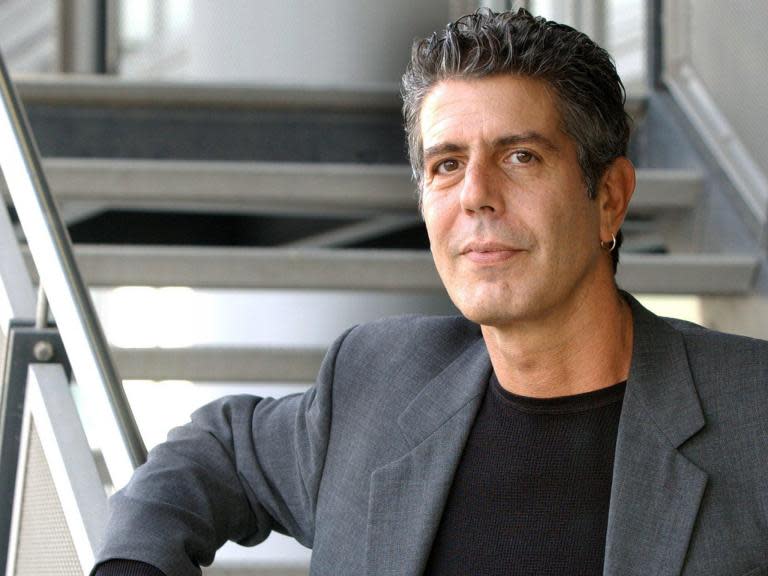

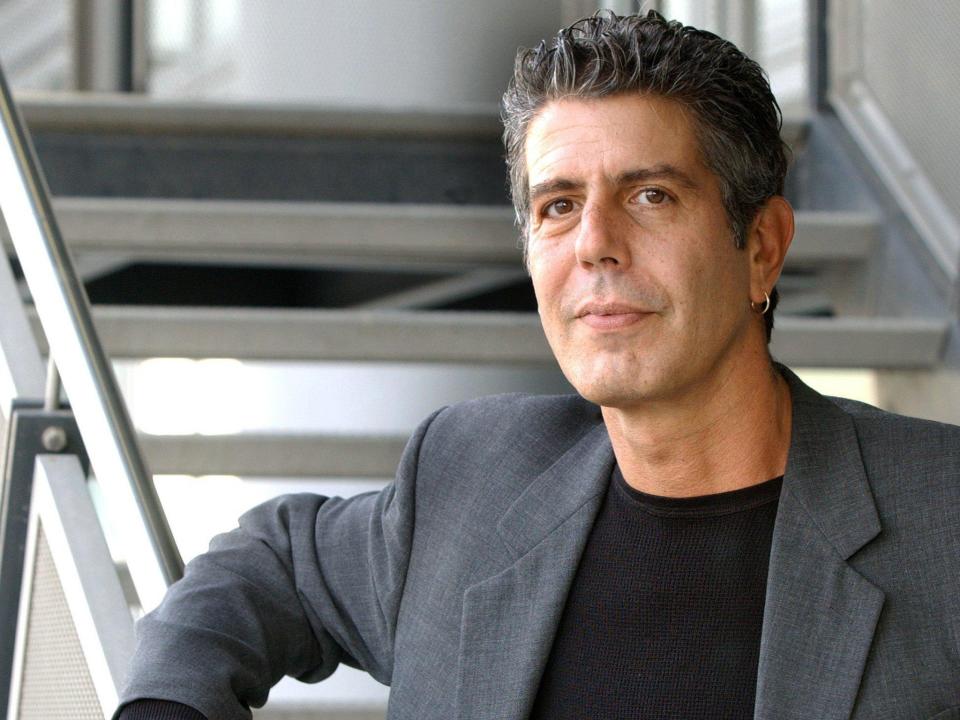

Anthony Bourdain inspired me to become a chef – but he also shone a light on the dark side of the kitchen

Anthony Bourdain made a point about not being called a chef once he got out of the kitchen. He was happy to be a TV personality, a food writer, a travel journalist, but once he went from working the stoves of Les Halles to working a pen or a camera angle, he was no longer a chef. To those of us inspired by his words to throw ourselves into the kitchen he was that and more – he was a god.

After a short lifetime of washing pots, the first real chef job I applied for, with its grotesque hours, endless burns and adrenaline rush weekends, was entirely prompted by his writing. After a couple of chapters of Kitchen Confidential, his first autobiographical book, I was hooked on the gritty glory that the fire and brimstone of cuisine could offer me. I’d scrubbed bench tops, poached eggs and reheated soup in kitchens before then, but his world was something entirely different – one of sex drugs and rock and roll that the saccharine sweetness of British TV chefs could barely touch on. To me, Gordon Ramsay may have been a brute, Marco Pierre White had a sociopathic reputation, but Bourdain was a rockstar.

With his word buzzing in my ears and no plan in my head I jumped on a bus to the nearest city. With his book bundled under my arm I walked into the biggest, busiest kitchen that would take me. I have often thought the reason I could walk in without a CV and walk out with a commis chef job was because the sous – then Gary Usher, now of Wreckfish fame – caught sight of the spine of Kitchen Confidential. Of course it was more likely because I was fresh meat, a willing lamb to the slaughter inspired by Bourdain’s masochistic vision. If nothing else, his philosophy of the kitchen as a place misfits could find glory on a Friday night service, of a world outside of the rules of regular life, where you could be threatened with the biggest knife in a chef’s roll one minute and gripped in a sweaty bear hug by them the next, drove me there and beyond.

We traded the book around, me and the other line cooks, until it had so many sauce splodges on it you had to peel apart the pages. It was a bible to us. With the earnest philosophy of a cook-turned-warrior poet, he taught us that if you mess up a dish you were messing up a long line of work from the producer to the plate, not to mention undermining the death of any creature that may have ended up in your service bin.

With sharp, cutting wit, he also told us about the time one of his superiors took five minutes out of the kitchen to sleep with a bride at her own wedding reception, such was his balance between the sacred and profane. It remains the most well read and well shared book on my shelf because Bourdain was able to capture the reckless abandon that inspired us all to get into the kitchen. Sure, food was a part of it, we all loved food, but what was more was that all of us, cut off from the rest of the world, partying while they slept and working while the partied, could find ourselves among a family of people with an equal commitment to heinous multilingual insults, a love of sharp objects and an ambition to make playing with fire a career.

The end of his story gives even greater weight to his words. While the exact reasons behind his death may never be known, he catalogued his relationship with various class A drugs as a young man in excruciating detail, kicking his heroin habit in the 1980s but still appearing to feel addiction’s lingering presence. Bourdain was honest about his struggles – he once said that he had been “a complete asshole”, a “selfish, larcenous, druggy” who “would have robbed your medicine cabinet had I been invited to your house”. It’s an industry wide problem that Bourdain could shine a spotlight on – last year Gordon Ramsey warned class A drugs were rife among kitchens after testing toilets in his 31 restaurants for cocaine and finding positive results in all but one.

A Unite survey last year found roughly a quarter of professional chefs in London were drinking to get through a shift while 51 per cent said they suffered from depression due to overwork. Personally I have known good chefs addled by powders and pills, balancing the manic ego required for the profession with the mental health issues it can produce. Bourdain’s end should serve as a reminder that kitchens have to work hard to protect those willing to put in 80 hour weeks of blood, sweat and tears.

But there is no death that can snub out the value of his life – a man who inspired writers and the public, but most of all a man caught up in a world of celebrity who reserved the greatest respect for the line cooks that spent their days with fire at their fronts and 100 diners at their backs. He may not have liked to have been called it, but there are no doubt queues of cooks who will regret not having had the chance to say “thank you chef”.

Vincent Wood is a former chef and freelance journalist