This Antarctic Ice Shelf Will Be the Next to Collapse

SAN FRANCISCO — Antarctica's crumbling Larsen B Ice Shelf is poised to finally finish its collapse, a researcher said Tuesday (Dec. 10) here at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

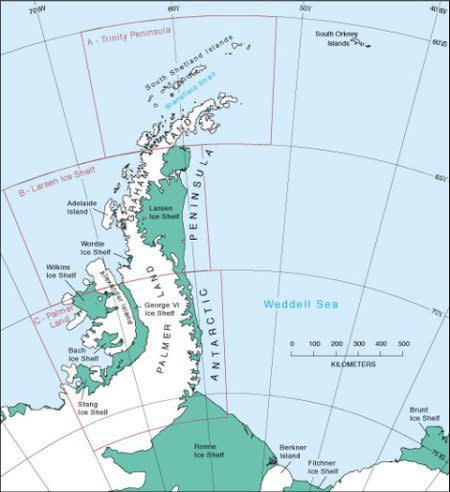

The Scar Inlet Ice Shelf will likely fall apart during the next warm summer, said Ted Scambos, a glaciologist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colo. Scar Inlet's ice is the largest remnant of the vast Larsen B shelf still attached to the Antarctic Peninsula. (Another small fragment, the Seal Nunataks, clings on as well.) In the Southern Hemisphere's summer of 2002, about 1,250 square miles (3,250 square kilometers) of the enormous Larsen B Ice Shelf splintered into hundreds of icebergs. Scar Inlet is about two-thirds the size of the ice lost from Larsen B.

Scambos and his colleagues at the NSIDC and in Argentina are tracking glaciers flowing into Scar Inlet so they can watch in detail how these ice rivers respond when their dams disintegrate. Many Antarctic glaciers have surged toward the sea after ice shelves collapsed, and leading scientists suggest that the shelves, the "tongues" of the glaciers that float on the ocean, act like dams. But Larsen B's disappearing act left little Scar Inlet holding back two big glaciers, and they seem to be tearing the ice shelf apart, Scambos said. Fractures and crevasses now incise the ice shelf. [Album: Stunning Photos of Antarctic Ice]

"It's becoming more and more like a floating independent island of ice than a plate bound to the coastline," Scambos said.

Scambos predicts that a warm summer — which causes widespread surface melting atop the ice shelf — will doom Scar Inlet. But the shelf's ice is so thin and fractured that it might collapse on its own, even without melting, Scambos said.

"It's possible that if there's a summer warm enough to clear out the sea ice, it will simply fall apart," he said.

But Antarctica hasn't had a very warm summer since 2006, so for now, the scientists wait and watch.

"When it breaks apart, we're really going to learn a lot more about what happens during this process," said Scambos, who will be visiting that area of Antarctica in January (summer in the Southern Hemisphere).

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Copyright 2013 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.