Ancient Indigenous lineage of Blackfoot Confederacy goes back 18,000 years to last ice age, DNA reveals

Members of the Blackfoot Confederacy have an ancient lineage that goes back 18,000 years, meaning that Indigenous peoples living in the Great Plains of Montana and southern Alberta today can trace their origins to ice age predecessors, a new DNA study reveals.

In the new study, published April 3 in the journal Science Advances, a team of researchers led by three members of the Blackfoot Confederacy investigated the genetic history of their tribes.

Comprising four related tribes — the Blackfeet, Kainai, Piikani and Siksika — members of the Blackfoot Confederacy historically included nomadic bison hunters and trout fishers. Their territory was divided in the mid-19th century by the U.S.-Canadian border, and in the late 19th century both countries' governments forced the Indigenous confederacy members to settle on reservations.

Since then, tribes in the Blackfoot Confederacy have had to defend their land claims and water rights, in spite of both archaeological evidence and oral traditions testifying to their deep history in the area. To provide an additional line of evidence that could help secure their treaty rights as well as to advance scientific knowledge of Indigenous genomic lineages, members of the Kainai Nation in Canada and the Blackfeet tribe in Montana partnered with scientists from multiple U.S. universities to investigate their genetic history.

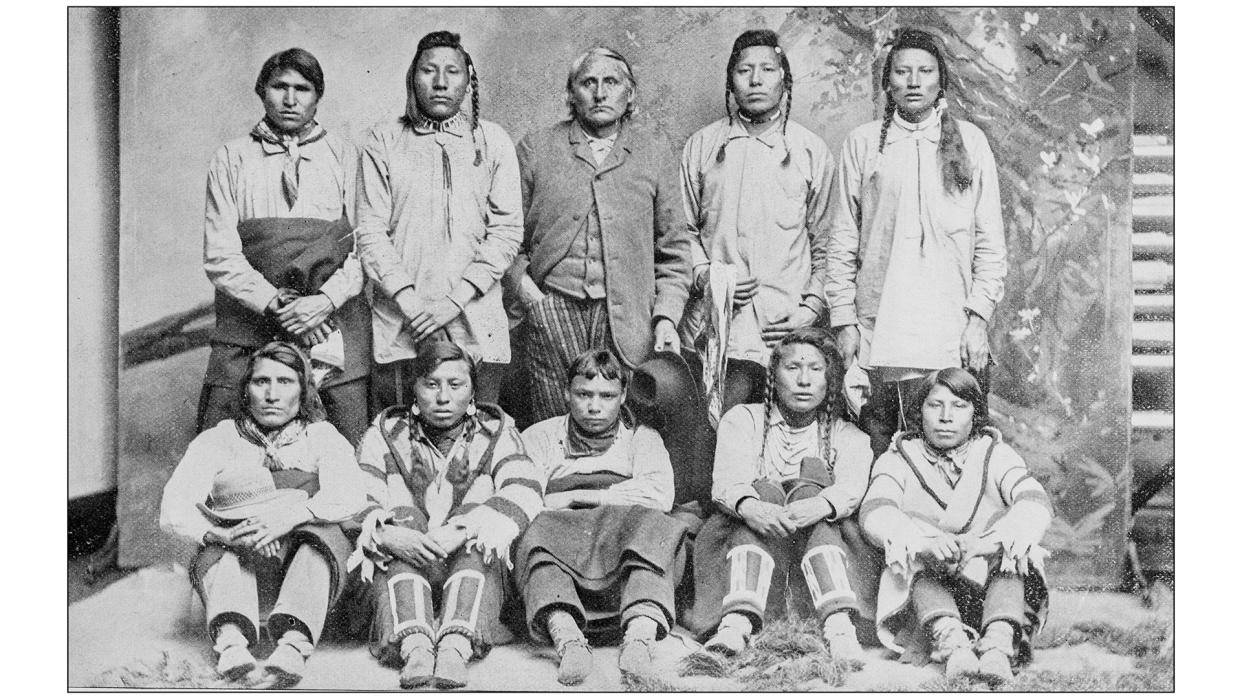

The research team took samples for whole-genome sequencing from seven skeletons that were carbon-dated to between 1805 and 1917, a period in which interactions between Blackfoot people and Euroamericans were increasing because of the fur trade. While DNA preservation was not ideal, as the samples came from skeletons that had been exposed on a burial platform, all the remains produced mitochondrial DNA information, or genetic data passed down from the maternal side. Additionally, six present-day tribal members were whole-genome sequenced.

Related: The 1st Americans were not who we thought they were

The genetic information revealed that the historical Blackfoot Ancestors and the present-day Blackfeet/Kainai shared a large fraction of their genome, suggesting a biological relationship. This continuity of genes was expected, but the team also found that this lineage was different from previously reported North and South American Indigenous groups. Based on statistical modeling, the team believes that the Blackfoot people split from other groups in the Late Pleistocene, around 18,000 years ago, as multiple population waves from a single source fanned out into the vast geographic land of the Americas.

In addition to identifying this genomic diversity that was previously unknown to science, the study is important because of its framing, according to Graciela Cabana, an anthropological geneticist at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville who was not involved in the research. "It's pretty obvious that this was written from more of an Indigenous voice," Cabana told Live Science in an email. "It's actually rare to see a collaborative study that is actually led by Indigenous community members on Ancestors."

Co-author Ripan Malhi, a genetic anthropologist at the University of Illinois, told Live Science in an email that genomics should be conducted by community members who can use this tool from an Indigenous viewpoint, "or through a community-collaborative approach where community partners have equal control in how the research is conducted and reported."

RELATED STORIES

—13 of the oldest archaeological sites in the Americas

—What's the earliest evidence of humans in the Americas?

—Did humans cross the Bering Strait after the land bridge disappeared?

This study comes out of the Blackfoot Early Origins Program, which documents Blackfoot persistence in their aboriginal territory, co-author Maria Zedeño, a research anthropologist at the University of Arizona, who co-directs the program, told Live Science in an email. "Genomics study is only one project in this program," Zedeño said, and "the tribal leaders reviewed its design and development at every step of the process."

Editor's note: Updated at 5:30 p.m. EDT on April 13 to note that there were three lead Blackfoot authors, not two as had been previously stated.