Worm-like ‘ancestor of all living beings’ found in Australia

The earliest common ancestor of almost all living animals (and humans) has been found in Australia – a wriggling worm which lived 555 million years ago, the size of a grain of rice.

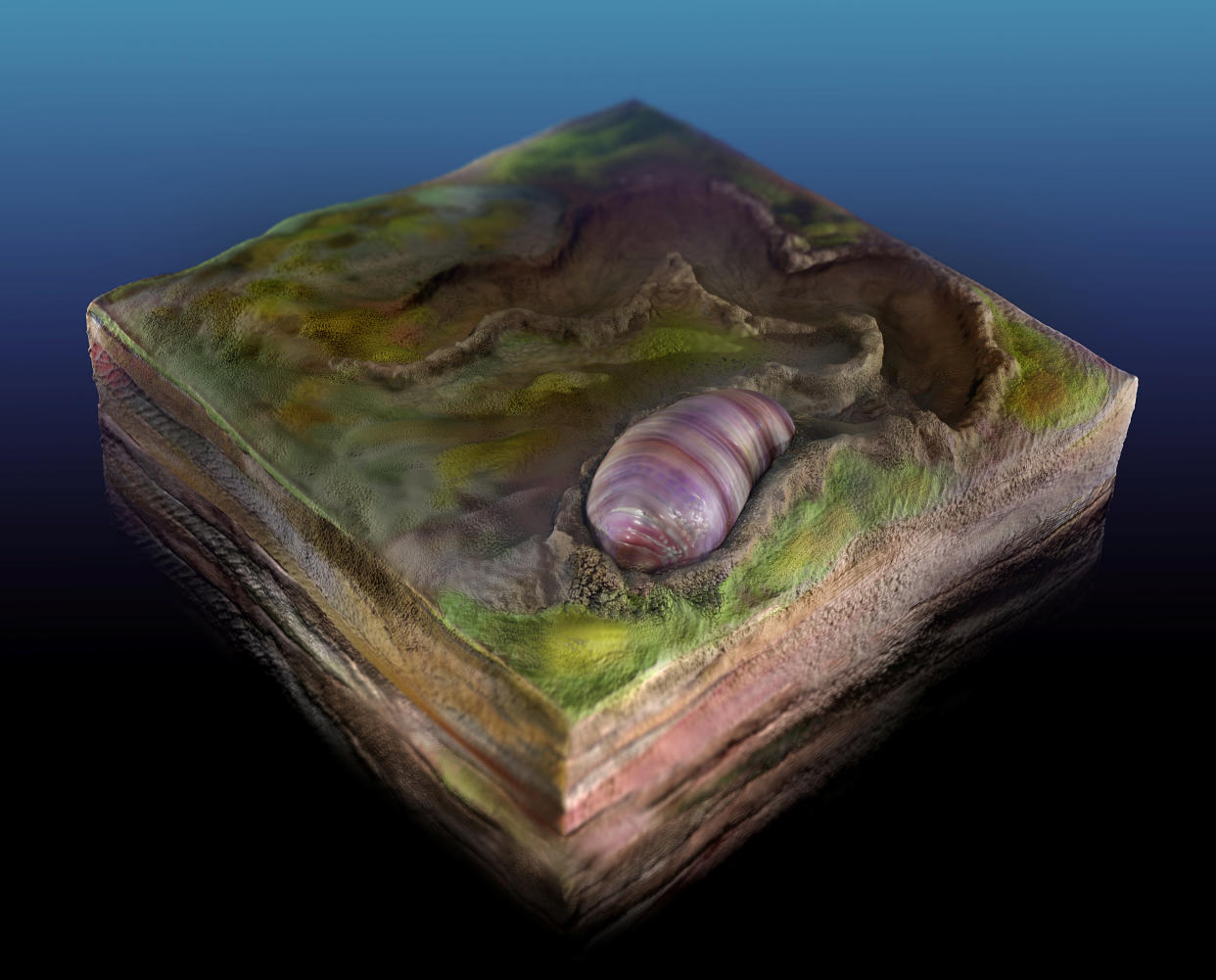

Scientists used a hi-tech 3D laser scanner to find remains of the creature near fossilised burrows in Australia, according to the study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

The worm-like creature, Ikaria wariootia, is the first ancestor with “bilateral symmetry”, meaning it had a front, back and sides, plus two openings at either end (with a gut in the middle).

Latest coronavirus news, updates and advice

Live: Follow all the latest updates from the UK and around the world

Fact-checker: The number of Covid-19 cases in your local area

Explained: Symptoms, latest advice and how it compares to the flu

Everything from insects to dinosaurs to humans is now organised around this sample simple body plan – but previous creatures were not.

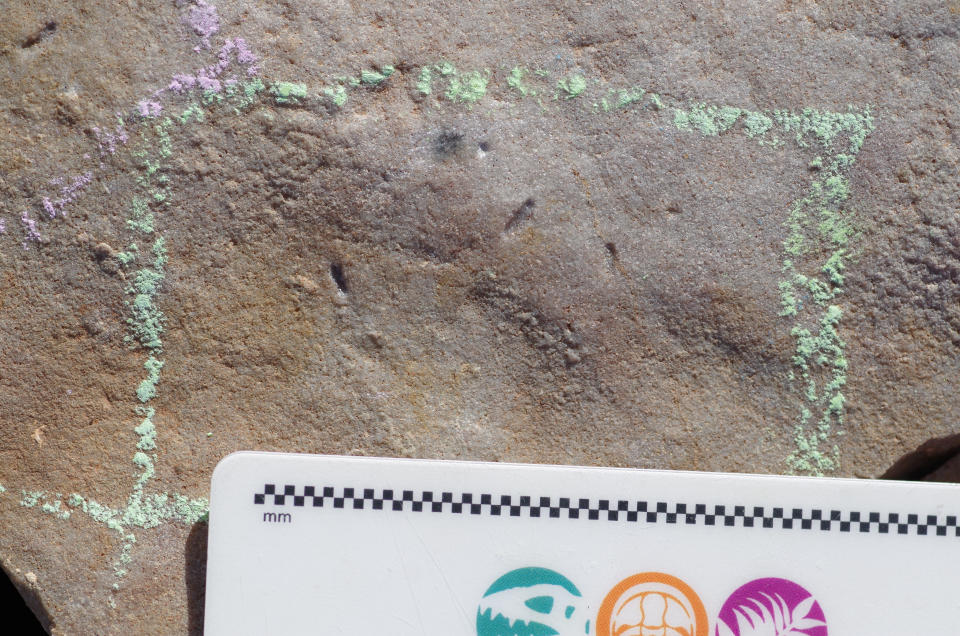

For 15 years, scientists agreed that fossilised burrows found in 555 million-year-old Ediacaran Period deposits in Nilpena, South Australia, were made by bilaterians, but there was no sign of the creatures which created them.

Read more; Ancient remains could rewrite history of human intelligence

Dr Scott Evans of the University of California, Riverside, and Professor Mary Droser noticed miniscule, oval impressions near some of the burrows.

With funding from NASA, they used a 3D laser scanner to reveal the regular, consistent shape of a cylindrical body with a distinct head and tail and faintly grooved musculature.

Dr Evans said: "We thought these animals should have existed during this interval, but always understood they would be difficult to recognise.

"Once we had the 3D scans, we knew that we had made an important discovery."

Read more: Ancient skull found in China could rewrite history of the human race

Prof Droser said: "It's the oldest fossil we get with this type of complexity. Dickinsonia and other big things were probably evolutionary dead ends.

"We knew that we also had lots of little things and thought these might have been the early bilaterians that we were looking for."

In spite of its relatively simple shape, Prof Droser explained that Ikaria was complex compared to other fossils from this period.

She said it burrowed in thin layers of well-oxygenated sand on the ocean floor in search of organic matter, indicating rudimentary sensory abilities.

The depth and curvature of Ikaria represent clearly distinct front and rear ends, supporting the directed movement found in the burrows.

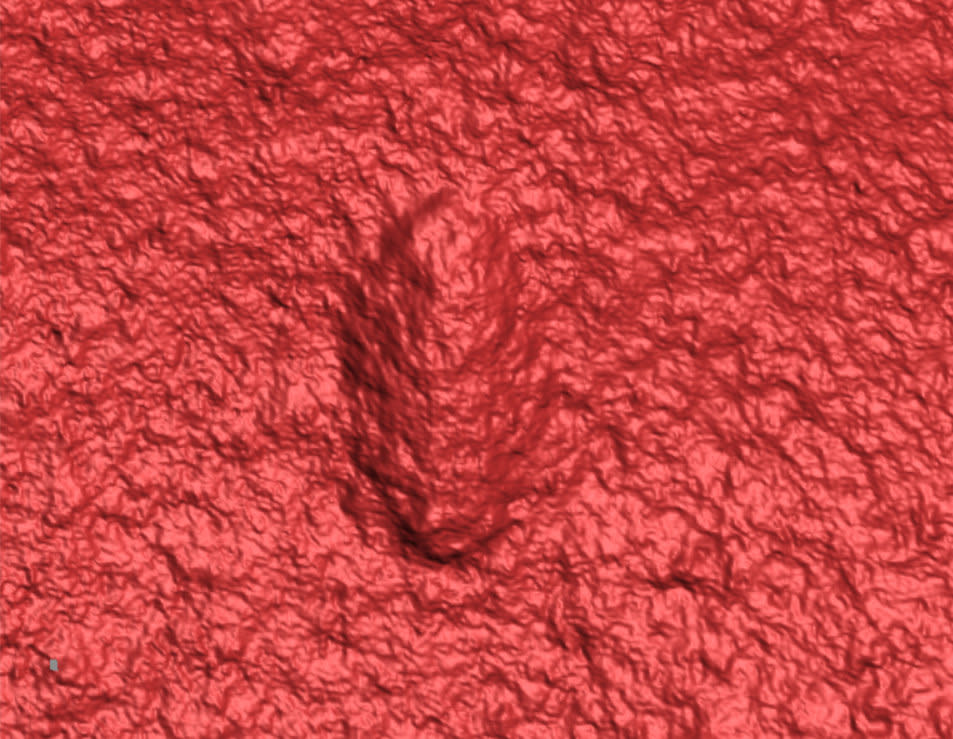

Professor Droser said the burrows also preserve crosswise, "V"-shaped ridges, suggesting Ikaria moved by contracting muscles across its body like a worm, known as peristaltic locomotion.

She explained that evidence of sediment displacement in the burrows and signs the organism fed on buried organic matter reveal Ikaria probably had a mouth, anus, and gut.

Professor Droser added: "This is what evolutionary biologists predicted.

"It's really exciting that what we have found lines up so neatly with their prediction."

Yahoo News

Yahoo News