The declining labor participation rate isn’t about immigration

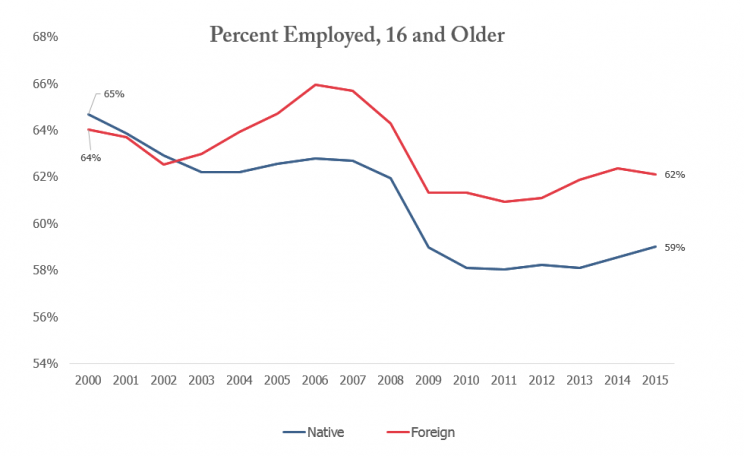

The labor-force participation rate, which measures the portion of American adults currently employed or looking for work, is frequently used as a key indicator of where the US economy stands. And according to a report this month from the Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC), the rate fell 5 percentage points between 2000 and 2015.

It is a troubling statistic. But contrary to what many pundits might like to pin it on, experts say the change is not due to immigration.

BPC finds that the decline is due to American-born workers’ increased inclination to turn to benefits like retirement, school enrollment and disability claims — that is, to leave the workforce.

According to the BPC report, between 2000 and 2015, the percentage of the US-born population (16 years old and up) either employed or actively seeking work dropped 5 percentage points. The percentage of the US-born population holding a job dropped 6 percentage points.

To be sure, immigration has been a hot topic in the current presidential campaign, in which Republican nominee Donald Trump has pinned much of the US economy’s woes on immigrants supposedly taking jobs.

“I think that it’s way too simplistic to say that the presence of immigrants drives native workers out of the work force,” Theresa Brown, BPC’s immigration policy director tells Yahoo Finance. The BPC report seeks to debunk the notion that immigrants are taking jobs; it examines retirement rate, school enrollment and disability claims from 2000 to 2015 as a way to explain the change in labor participation.

“The notion that immigrants displace workers is really a fallacy based on the idea that there is a fixed number of jobs in the economy and that one job that somebody else takes is one that somebody else can’t take,” says Kenneth Megan, a BPC policy analyst and the report’s author. “The reality is that the economy is dynamic and really depends on supply and demand.”

Foreign-born workers tend to face more barriers in the workforce than native-born workers: They are less likely to qualify for full Social Security benefits; they are less likely to qualify for federal disability programs due to having fewer work credit-hours; and lack of proficiency in English can limit their access to education.

While American-born workers don’t face these kinds of barriers, other forces like globalization have reduced employment in the US, particularly in manufacturing. And these outside forces could have a much bigger impact on employment than immigrants who take low-paid jobs in the US.

“Immigration is not the biggest problem that these groups have,” says Harry Holzer, professor of public policy at Georgetown University, referring to US-born workers who believe immigrants are taking their jobs. “These groups have been more adversely affected by digital technologies and other kinds of globalization like imports and exports and weakening unions.”

It also turns out that foreign and native workers often don’t target the same occupations anyway. “Immigrants and native-born workers do not usually compete for the same jobs,” says Silva Mathema, senior policy analyst at Center for American Progress. “Instead, many immigrants are complements to US workers.”

People love to argue about how much immigration affects American-born workers, but a better question is why, over the past 15 years, more American-born workers are turning to routes like retirement, school enrollment and disability claims earlier in life. Some potential explanations include baby boomers nearing retirement age, and “prime age” workers (25-54) dropping out of the labor force.

“I think a lot of it had to do with the great recession,” Kenneth Megan says. “If you lose your job and you are 50 years old and native-born American, you might opt to retire or go back to school. You are more likely to do that than in a good economic time.”

Contrary to what some politicians might like to say, many economist say that in the long run, immigrants are good for the American economy, and don’t displace American workers. “On average,” Silva Mathema says, “many have found that [immigrants] have a positive effect on native-born workers.”

—

Minyoung Park is a reporter at Yahoo Finance.

Read more:

How the Supreme Court is hurting the economy by killing immigration reform

America’s brick-and-mortar retailers are vanishing

A mysterious US industry has been growing since the recession — psychic services