Researchers exonerate 'Patient Zero' in U.S. AIDS epidemic

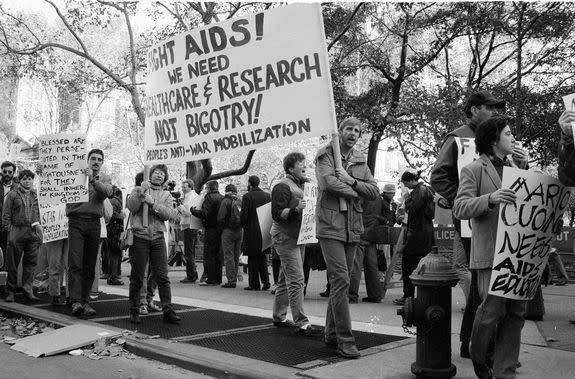

To Richard Burns, New York City in the 1980s felt like a war zone.

When he wasn't caring for friends stricken with AIDS or mourning their death, Burns was protesting in the streets, urging public officials to confront this mysterious disease afflicting the gay community.

"It felt at the time like we were in a war, and the enemy was not only AIDS; the enemy was our own government," said Burns, who headed New York's Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender (LGBT) Community Center from 1986 to 2009.

SEE ALSO: Scientists see early progress on potential HIV cure

"You were living with fear and constant dying and caregiving and shell shock," he told Mashable. "There was a lot of anger and anguish in our community."

Researchers say they now have answers about the early years of North America's outbreak of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).

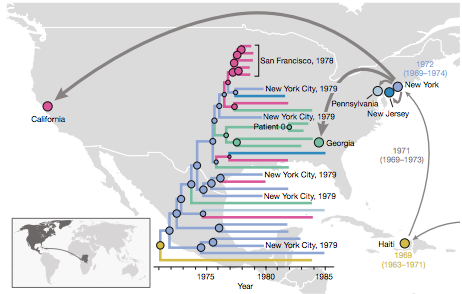

What they found is surprising: the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) — the virus that causes AIDS — first "jumped" from the Caribbean to New York City in 1970 or 1971, roughly a decade before AIDS began claiming hundreds of thousands of U.S. lives.

From New York, the virus then spread across the country.

Image: AP Photo/Rick Maiman

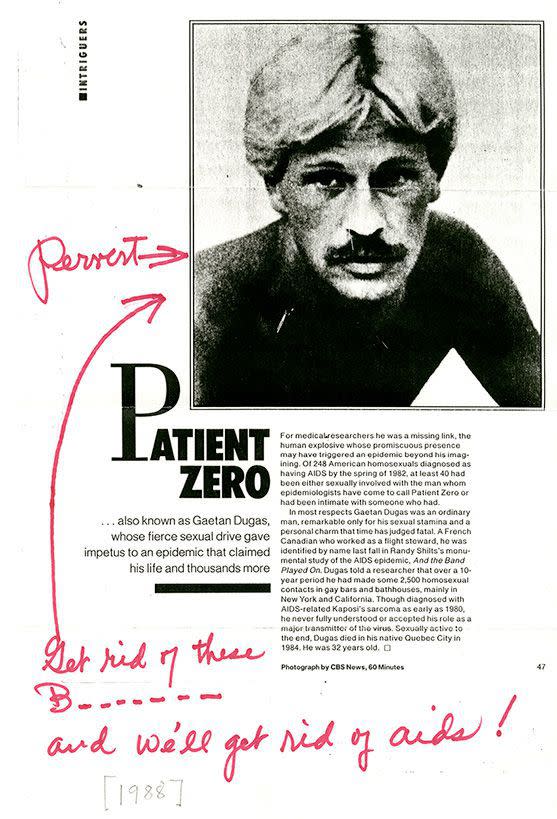

The study, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, may also finally debunk the myth that Gaetan Dugas, a male flight attendant referred to as the so-called "Patient Zero," first brought HIV out of Africa and into the Western gay community in the early 1980s.

Dugas died of complications from AIDS in 1984.

Though earlier studies had cast doubt on the "Patient Zero" narrative, the Nature study proves there is no biological or historical data to support the story, said Richard McKay, a co-author of this week's study and a scholar specializing in the history of public health at the University of Cambridge in England.

Image: National Library of medicine

"This individual was simply one of the thousands infected before HIV was recognized," he said on a Tuesday conference call with reporters.

According to the new research, once HIV arrived in the city, New York then became a "crucial hub" from which the virus spread across the continent, the researchers found based on an examination of genetic and historical data.

Tracing the virus

HIV is mainly transmitted through sexual contact or by using infected needles, although tainted blood transfusions can spread the virus and women infected with HIV can pass it to their children. HIV weakens a person's immune system by destroying important T-cells that fight disease and infection.

If left untreated, HIV can lead to the development of AIDS, which leaves people extremely vulnerable to other types of infections without treatment. Around 36.7 million people worldwide had HIV/AIDS at the end of 2015, including 1.8 million children, according to UNAIDS.

Decades later, U.S. cases of AIDS have drastically declined as drug therapies and prevention education improved. But questions had remained about how this deadly condition first arrived on America's doorstep.

Image: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

For the Nature study, the researchers began by screening more than 2,000 blood serum samples collected in New York and San Francisco between 1978 and 1979.

The samples belonged to men who had sex with men, and who had participated in a vaccine study for Hepatitis B, another sexually transmitted virus, said Michael Worobey, a co-author of the study and an expert on virus evolution at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

Image: CDC

Since many clinics and research facilities toss out old samples over time, Worobey said it was "miraculous" they were able to find these 2,000 samples.

Yet all of the nearly 40-year-old samples had degraded over time. So Worobey said he borrowed ideas from the field of ancient DNA research and developed a technique to "stitch together" complete genomes.

Using this technique, the researchers recovered eight viral RNA genome sequences of the strain of HIV that started the North American outbreak. These sequences are now considered the oldest HIV genomes in North America.

"It's direct evidence of many years of circulation of this virus in the United States before HIV and AIDS were finally recognized," Worobey told reporters on a press call.

The researchers found extensive genetic diversity in the earliest HIV genomes they recovered from New York, which indicated the start of the outbreak.

This particular strain of HIV likely first emerged in the Democratic Republic of Congo in the early 20th century. At some point, a chimpanzee first spread the virus to a human, who later spread it to other humans. Subtype B endured for decades, and by the 1960s, it crossed the Atlantic and took hold in Haiti and the Caribbean.

Image: michael worobey/nature

From there, the strain arrived in New York, then traveled to San Francisco, South America, Western Europe, Australia and parts of Asia, Worobey said.

The methods used in this study also have implications beyond the field of HIV/AIDS, experts said.

These new molecular techniques to restore genetic material from aging tissue samples could help scientists study the outbreaks of other infectious diseases, such as the Ebola and Zika viruses, said John Coffin, a professor of molecular biology and microbiology at Tufts University in Massachusetts.

"The study really tells us what we need to know, in a sense, about how epidemics spread, how they develop," said Coffin, who was not involved in Wednesday's study.

"It resets our understanding of the very early days [of AIDS] in a very useful way," he told Mashable.

Tracing Patient Zero narrative

While the study proves when HIV arrived in North America, it doesn't reveal who or what first brought the virus.

An individual of any nationality may have brought the virus from the Caribbean, or the virus could've traveled in blood products imported from Haiti. "How the virus moved from the Caribbean to the United States and New York City in the 1970s is an open question," Worobey told reporters.

What is certain, however, is that Dugas, or "Patient Zero," was not to blame for spreading the virus to North America.

Image: Shaun Heasley/Getty Images

Researchers studied the HIV genome of this man and found it appeared typical of U.S. strains that were already circulating in the 1980s.

They also traced the historical origins of the Patient Zero myth.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had interviewed him for a 1984 cluster study. Investigators first identified him as Case 057, and then "Patient O," because he came from "Out(side)-of-California."

Through a typographical error, the number "0" replaced the letter "O," hence "Patient Zero."

Dugas, who was born in 1952, was a flight attendant for Air Canada in the 1970s and 80s. He said he had about 250 different partners a year between 1979 and 1981, close to the average of 227 partners reported by other patients.

The man gave CDC the names of 72 sexual partners, eight of whom had developed AIDS. Four of those men were in southern California, and four were in New York City.

At the time, the investigators thought he matched the profile of someone who may have helped spread the disease quickly among men who have sex with men. But researchers never insinuated that Patient Zero was the source of the North American epidemic, and they never publicly identified him.

Instead, the journalist Randy Shilts named the individual in his 1987 book And The Band Played On and highlighted the man's "unique role" in the HIV epidemic. That book later became a movie starring Alan Alda and Matthew Modine (the latter of Stranger Things fame).

Image: AP Photo/Dennis Cook

Shilts, who was gay and died of AIDS-related complications in 1994, had sought to highlight the epidemic's heroes and victims and shift the tone of the national public debate. Media coverage later reinforced Shilts' suggestions.

Richard Burns, the activist in New York, said the narrative around Patient Zero was largely irrelevant to him and his peers as they struggled through the AIDS epidemic.

Burns is now interim executive director of North Star Fund and is on the board of the NYC AIDS Memorial, which will open in Manhattan's West Village neighborhood on Dec. 1 on World AIDS Day.

"We really didn't care about so-called Patient Zero at all," Burns recalled.

"People were getting sick, the government didn't care, drug companies were not responding appropriately, the media was homophobic and AIDS-phobic," he said. "We were living in a world where the larger culture seemed to not care about us."