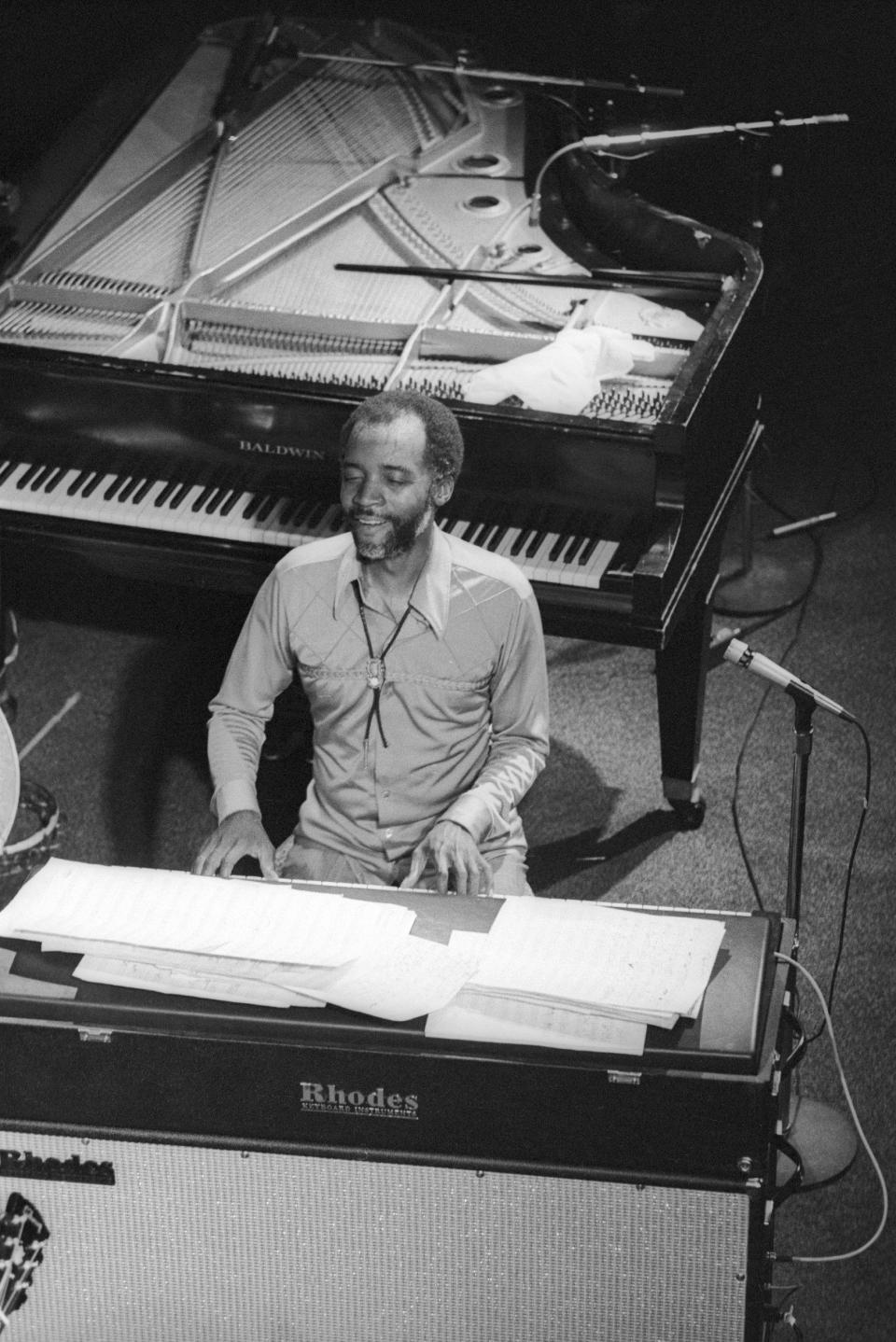

Ahmad Jamal, jazz giant who inspired Miles Davis with his intense, minimalistic style – obituary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Ahmad Jamal, who has died aged 92, was a distinctive jazz pianist and composer in his own right as well as an important stylistic influence on others, notably Miles Davis.

Jamal’s style, which has been described as “minimalist”, was characterised by a canny use of space and meticulous timing. Although he worked mainly in the simple piano-bass-drums trio format, his approach was orchestral, effectively deploying rich variations in harmony and texture. He was not given to bravura displays of virtuosity.

Ahmad Jamal was born Frederick Russell Jones on July 2 1930 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and began playing the piano aged three. He started formal lessons at seven and was performing with local bands at 11, under the name Fritz Jones, which he changed temporarily to Freddie Jones during the war years. He joined the American Federation of Musicians at 14 and was touring professionally at 17.

He formed his own trio, the Three Strings, consisting of piano, guitar and bass, in 1950. The following year they were discovered by John Hammond, the most famous talent scout in jazz history, and signed up by him to the Okeh record label.

At about the same time, Fritz Jones embraced Islam, changed his name to Ahmad Jamal and thereafter refused to answer to any other (in 1986 he would sue the critic Leonard Feather for using his former name in an article). The band’s name was also changed to the Ahmad Jamal Trio. Its recordings for Okeh included two notable Jamal compositions, the original version of Ahmad’s Blues, which was to become something of a jazz standard, and Pavanne. This latter tune bears a remarkable harmonic similarity to a later Miles Davis piece, So What.

In 1955, having moved to the Argo label, the trio recorded Chamber Music of the New Jazz (released the following year), their first album to elicit enthusiastic comment from Miles Davis. It was also around this time that Jamal insisted on using the term “American classical music” in place of “jazz”. In the following year, drums replaced the guitar in the trio and Jamal took up a residency in the lounge of the Pershing Hotel in Chicago.

This quickly became the most fashionable venue in the city, drawing capacity audiences. It was here that the trio recorded the album At the Pershing: But Not for Me, which, against all expectations, became a pop hit, climbing to No 3 in the US album charts. It remained in the Top 10 for 108 weeks. One piece, Poinciana, proved so popular that Jamal adopted it as his signature tune.

Throughout this period, the mid-to-late 1950s, Miles Davis expressed his admiration for Jamal’s restrained yet intense style by praising him at every opportunity and by borrowing liberally from his repertoire, both original compositions and standards. Many numbers which came to be permanently associated with Davis, such as On Green Dolphin Street, New Rhumba, It Could Happen to You and Ahmad’s Blues, derived from this source. Davis even had Red Garland, his pianist at the time, record Jamal’s version of the folk song Billy Boy virtually note for note.

In 1960, following a tour of North Africa and the Middle East, Jamal opened his own club, the Alhambra, in Chicago. It served Middle Eastern food and no alcohol. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it closed after seven months, although two successful live albums were recorded there.

There was no repeat of the Pershing hit, but Jamal’s albums continued to enjoy success well beyond the confines of the strictly jazz audience. Jamal at the Penthouse (1959) featured the trio surrounded by a string orchestra.

Jamal disbanded the trio in 1962 and took a year off, returning with a new trio after recording Macanudo, a solo album with strings. His style grew somewhat less restrained, although it lost none of its subtlety, and he began making occasional use of the Fender Rhodes electric piano.

His 1967 album Cry Young gained a brief placing in the pop charts and Freeflight, recorded live at the 1971 Montreux Jazz Festival, was highly acclaimed in the jazz press. It was now generally agreed that live performance suited him better than working in a recording studio.

In the soundtrack to the 1970 movie, M*A*S*H, Jamal’s version of Johnny Mandel’s theme tune is heard repeatedly. Later, Clint Eastwood used several album tracks, including Poinciana, in his film The Bridges of Madison County.

Jamal continued to produce albums almost annually through the 1980s and 1990s, many of which figured in the jazz charts. He found a growing audience in Europe, particularly in France, and eventually signed a contract with the Parisian producer Jean-François Deiber to handle his recording affairs.

Their first release, The Essence, Part 1 (1994), marked a departure, in that he shared the limelight for the first time with a saxophonist, George Coleman. It was received with great critical applause and demonstrated his ability to rise to the challenge of working on equal terms with a player of equally forceful personality. It was followed in 1997 by a similar album, Big Byrd: The Essence Part 2, with the trumpeter Donald Byrd.

Jamal celebrated his 70th birthday with a concert at L’Olympia in Paris, which was released as Ahmad Jamal à l’Olympia – there were two more live albums from the venue, featuring Yusef Lateef – and followed it in 2003 with In Search of Momentum. He continued working into his 80s with such albums as Saturday Morning (2013).

Ahmad Jamal was married three times; his third wife, and manager, was Laura Hess-Hay. They divorced in 1984 but she continued to represent him. He is survived by a daughter from his second marriage. Another daughter predeceased him in 1979.

Ahmad Jamal, born July 2 1930, died April 16 2023