In Afghanistan, Where Breast Cancer is a Death Sentence, Women Fight to Save Lives

Sherbano gripped her children tightly and wept. She had a hard mass growing in her breast, and a dangerous 700 kilometre journey ahead of her.

At 30, she had never left home before, never parted with her nine children, or her husband – even for a day. But on a sweltering day this August, Sherbano said goodbye to her family. She didn’t know if she’d ever see them again.

Her husband had scraped together a few hundred dollars – money that could have supported their impoverished family for several months – selling grapes from vines in front of their mud house in war-ravaged Helmand, in southern Afghanistan. Her family hoped it would be enough to get her to the bustling capital, Kabul, where doctors in the country’s sole oncology ward might save her life.

They worried she might die on the days-long bus journey through Taliban strongholds, along winding, unpaved roads and across government checkpoints. But despite clashes between militants along the way, Sherbano made it to Kabul.

There, perched on concrete ground outside Jamhuriat Hospital for days with dozens of other sick patients, she waited for a bed.

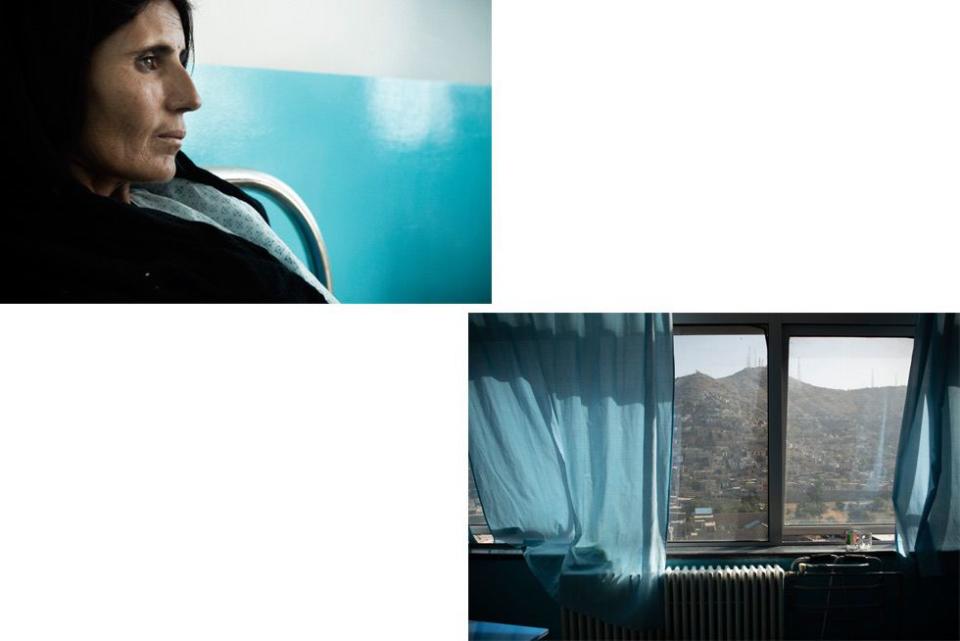

‘Only God knows if I’ll be fine or not,’ Sherbano says quietly, resting in a blue hospital bed.

She’s one of thousands of women suffering from breast cancer in Afghanistan. In the UK, an estimated 80 percent of women survive for at least five years with breast cancer, and an estimated 90 percent of women will survive in the US during that same time frame. But the disease is often a death sentence for Afghan women.

In Afghanistan, there is only one oncology department in the entire country. There is no readily available chemotherapy, and no radiation.

Here, breast cancer is the second leading cause of death of women behind maternal mortality, according to the World Health Organisation and medical experts. And while maternal mortality rates have decreased significantly, the rates of breast cancer survival are not improving. Sound statistics are hard to come by in Afghanistan, but there’s evidence that more women might die from breast cancer than they do from war.

Like most of the Afghan women who end up at Jamhuriat Hospital, with its seafoam green hallways packed with desperate patients waiting for beds, Sherbano has late-stage breast cancer.

There is only one practicing oncologist in all of Afghanistan, according to doctors here – Dr. Zabi Stanekzai, head of cancer diagnostics at Jamhuriat Hospital.

Thirty-three-year-old Dr. Sohaila Niazi, however, plans to become the second – and the country’s first-ever female oncologist. She trained in Pakistan and specialises in cancer treatment. She’s also Sherbano’s doctor, the woman tasked with trying to save her life despite limited means and time that’s running out.

Dr. Niazi hopes to travel abroad soon to complete an oncology residency program, which is not offered in Afghanistan, though she says she needs a financial scholarship to do so. At Jamhuriat Hospital, Sohaila works alongside her 27-year-old sister Najia, who says she's the country’s sole cognitive behavioural therapist working with patients diagnosed with cancer.

‘I’m happy to be here,’ Sherbano says, a slight smile spreading across her face. ‘They’re like my sisters.’

In Pakistan – where Sohaila and Najia grew up and studied, and where many Afghans go for medical treatment if they can afford it – the sisters learned there were barely any cancer doctors back in Afghanistan.

‘I must go,’ said Sohaila, who told her father she wanted to be a doctor at age two. Afghanistan ‘needed’ her. She wanted to save as many women as she could.

Doctors like Sohaila are rare, though increasing numbers of women are becoming nurses, midwives, and doctors. Across Afghanistan, poverty, war and a shortage of trained medical professionals make it even more difficult for women to seek medical care. Many Afghan women are not allowed to – or choose not to – see male doctors and nurses, due to cultural norms that keep men and women who are not related largely segregated in public life.

One year ago, while Sherbano breastfed her eighth child, she found a hard mass.

‘I didn’t know what it was,’ she says, nervously re-adjusting her headscarf. Sherbano worked up the courage to show her breast to her mother-in-law, who urged her to see a doctor.

In Helmand, she only found a male doctor, to whom she could not show her breast. Instead, she showed a female nurse, who described it to the male doctor, who then told her to get medical treatment in Pakistan, which Sherbano’s family could not afford.

Months later, after Sherbano lost life-saving time, she managed to make it to Jamhuriat, where she’s relying on donations to pay for chemotherapy – treatment that likely won’t save her. At best, they say, Sherbano has a year left to live.

It’s a story doctors like Sohaila hear over and over again.

‘I was ashamed to go to a doctor,’ says another woman, Abida, who is 25-years-old with five children. An IV is taped to her emaciated arm for another round of chemotherapy. She pulls up her hospital gown showing deep scarred gashes on her legs, and four missing toes. She survived a rocket attack on her house years ago, during clashes between Taliban and international forces allied with the Afghan military. But it’s the cancer that might kill her.

Back home in Jalalabad, in eastern Afghanistan, the Taliban closed schools for girls in her village when she was younger, and the only knowledge she had about health was passed down from other female family members. She had never heard the world ‘cancer’ before arriving at Jamhuriat Hospital.

In Afghanistan, where many people lack basic education and remain illiterate into adulthood, cancer is equated with almost certain death.

Much of the sisters’ job is focused on convincing patients and their families to consider treatment – whether that’s a mastectomy, chemotherapy or if they can afford it, radiation treatment in Pakistan or elsewhere. Many clinics and hospitals in Afghanistan do not tell patients they have cancer, specifically.

In doing so, doctors say, they’d take away all hope. Some husbands do not inform their wives – instead, they say, they’re simply ‘sick.’

'She’ll only suffer more,' says Jomaa, whose wife Safia has a baseball-sized mass in her breast and likely only one year left to live. 'She’ll be hopeless if she knows.'

Sohaila and Najia have struggled with this policy, instead trying to inform women as much as possible and work around cultural norms regarding consent and access to information in which husbands and fathers routinely make potentially life-altering decisions for women.

Even if they can convince women and their families to agree to treatment, paying for it is another hurdle.

Right now, patients have to bring in their own chemotherapy medication smuggled from Pakistan and sold in Afghan pharmacies. Hospitals do not yet provide the chemotherapy medication, but most patients can’t afford it anyway. Sohaila, Najia and the medical staff at Jamhuriat pool together what they can out of their own pockets to help pay for critical patients.

‘I work with them with my heart and soul,’ says Sohaila. On any given day, the two sisters can be found tending to patients in the oncology ward, their tunics and headscarves in colours of fierce blues, reds, and oranges flowing behind them.

They demand a presence.

When US-backed Afghan militias drove the Taliban out of Kabul in 2001, the task ahead to stabilize and rebuild was a daunting one. Afghanistan and the international community were focused on the basics – and breast cancer wasn’t on the radar.

‘We lost everything during the war,’ says Dr. Nasrin Oryakhil, a gynecologist and obstetrician and head of the Afghanistan Medical Council, who says the state of breast cancer research and treatment in Afghanistan is still at ‘stage zero.’

The international community has poured billions of dollars, and thousands of troops, into military efforts in Afghanistan. And much international funding has gone into health efforts over the past two decades, with particular focus on curbing the alarming rate of women and babies dying during childbirth.

But with one oncology ward in the whole country, and barely any way to effectively treat Afghans with cancer – particularly women – Dr. Oryakhil says there needs to be more funding devoted to cancer diagnosis, research and treatment in Afghanistan.

‘It’s very critical,’ she says.

More funding could be on the table soon – £19.5 million or more. The Afghan government is currently in talks with Global Medical Partners, a US-based health organisation, to build and support a diagnostic, treatment and research centre affiliated with Jamhuriat Hospital. It would be staffed with doctors like Sohaila. If all goes as planned, the centre will include access to radiation and chemotherapy.

J. Scott Broome, head of the Global Medical Partners, acknowledges the steep hurdles Afghanistan faces surrounding breast cancer. Such a centre, even if well-funded and staffed, will not be able to treat everyone in Afghanistan. But he’s hopeful it will save lives.

‘We have to start somewhere,’ he says.

At present, there is there is no widespread breast cancer awareness campaign, apart from yearly October education programs for school girls marking Breast Cancer Awareness Month, and occasional government sponsored events.

Nurses from Jamhuriat Hospital have taken outreach into their own hands, carrying around pink pamphlets about breast cancer to hand out at family dinners and holiday gatherings, and at parks, where families picnic on the weekends to escape the grind of the city.

Doctors like Dr. Oryakhil say it’s difficult to talk publicly about such sensitive issues like breast health in a conservative country like Afghanistan. But that doesn’t stop her from trying.

Meanwhile, war still plagues Afghanistan, with militants controlling large swaths of the country and blocking women’s access to education and life-saving healthcare.

In July, militants attacked a midwife training centre with explosives, killing several, including a driver and a guard. Dozens of female health workers escaped unharmed. Militants have routinely targeted female health workers and Afghans who vocally support women’s rights, particularly those working alongside foreigners.

In January, militants disguised as emergency health workers drove an ambulance through a security checkpoint in central Kabul, claiming they were headed to Jamhuriat Hospital. They detonated a car bomb on the busy street in front of the hospital, killing nearly 100 people.

‘It was the first time I had ever heard that sound in my life,’ Najia said, staring at her shoes.

Nurses huddled together, weeping. Najia went bed to bed trying to calm her patients as bloodied victims – including doctors – poured into the already overcrowded hospital.

After the attack, the sisters returned to the hospital without a second thought, driving down the very road that was bombed. Life had to go on, as it does after every attack, after every bombing. There were women at the hospital who depended on them.

The sisters know they won’t be able to save most of the women who come to them for help, unless something drastically changes – better health outreach and education, more health facilities, quicker diagnoses, and improved access to chemotherapy and radiation across the country, not just in Kabul.

For now, Sohaila, Najia and their colleagues can only do so much for the women who come to them, desperate for help.

In August, one of their patients, Kamina, died quietly in the oncology ward, where the light from the hillside pours in through powder blue curtains. Before Kamina died, leaving behind nine children, she prayed for Sohaila and her sister.

Sohaila cried the whole way home that day. She had paid for Kamina’s chemotherapy. But it was too late – a long delayed diagnosis and treatment weren’t enough to save her.

It would be easy to give up, to leave this oncology ward for better pay, for a break from the heartache.

But Sohaila is not haunted by the memories of women she couldn’t save. Instead, they will her forward, in search of answers and a future where Afghan women aren’t destined to die.

It's women like Shafiqa, from Kandahar, who showed up at Jamhuriat Hospital asking for ‘Doctor Sohaila,' who give her hope.

Some women, like Shafiqa, are lucky – they were able to diagnose and respond to her breast cancer early enough, with chemotherapy paid for in part by Sohaila herself. Shafiqa’s most recent CT scan showed that she was, at least for now, cancer free.

‘We just heed their prayers,’ Sohaila says, blotting away tears with a tissue. And with that, the doctor straightened her dress, took a deep breath, and walked into the hallway to tend to Sherbano before her long journey home to Helmand.

'The Warriors' is a year-long reporting project by ELLE and the Fuller Project for International Reporting, funded by the European Journalism Centre via its Innovation in Development Reporting Grant Programme.

('You Might Also Like',)