'Abandon all hope:' Ukraine’s wounded warriors compare military medical system to the Inferno

Editor’s Note: This story is based on dozens of interviews with Ukrainian active servicemen, veterans, and experts with knowledge of Ukraine’s military medical system. Some of the soldiers and veterans in the story are identified by their first name or callsign only because they fear retribution as they continue fighting for their benefits or to be discharged following injuries. One soldier, entangled in a legal battle to be discharged, is identified under a pseudonym. The Kyiv Independent corroborated their stories by reviewing their medical records and listening to recordings of some of their conversations with doctors.

The last thing National Guardsman Yurii Sluchynskyi, callsign Luch, remembers from that summer day in 2022 is holding a sniper nest with his team in Sievierodonetsk, listening for enemy weapons.

Then, the Russian airstrike hit, folding a big part of the building down on top of them.

When they pulled Sluchynskyi’s broken body from the rubble, the Ukrainian intelligence operators thought he was finished.

Out of his whole team, he was mangled the hardest. His legs were sticking out at odd angles, he was convulsing and struggling to breathe. There was a hole the size of a small apple in the side of his head and his eyes showed signs of a massive hematoma.

The boys of Ukraine’s Main Intelligence Directorate put him in a helicopter just in time. He credits their rescue and the will of God for his survival.

After many months spent recovering, with a metal plate now sealing his broken skull, Sluchynskyi regained independent function but his fighting days were over. Before he could go home and re-enter civilian life, he just had to go to a medical commission to do his physicals, arrange the medical discharge, and apply for his legally entitled disability benefits.

After what he survived, Sluchynskyi didn’t expect his daily life to take another turn for the worse. But the Ukrainian military medical bureaucracy seemed determined to add insult to injury, making him fight for adequate treatments, his combat pay, and his freedom every step of the way.

"Sometimes people say war is hell,” Sluchynskyi told the Kyiv Independent. “The hell is when you return from the war (to face) the indifference. It is very demotivating.”

The Kyiv Independent interviewed him and dozens of other veterans, military personnel, and civilian volunteers helping the military. They describe a military medical system that’s fundamentally broken on every level, no matter where you are, no matter how you’re injured. As a reward for fighting Ukraine’s battles, veterans have to fight a callous, sometimes corrupt, outdated bureaucracy that’s often working against them, while they are at their most physically and psychologically vulnerable.

Military medical commissions (abbreviated locally as VLK) are central to many issues. A VLK is a quorum of doctors who decide the medical status of service members passing through their hospital. Many doctors have questionable competence and integrity, according to veterans. Ukraine’s obsolete military protocols have also done a lot of damage.

Starting treatment in spring 2023, Sluchynskyi got the full experience. He sat in long lines of injured veterans for days at a time. He ran around trying to track down medical specialists, with extremely tight schedules and deadlines. According to him, their examinations were perfunctory at best, actively diminishing the severity of his injuries at worst.

To complete his medical checkups, his unit made him find two eyewitnesses to testify that he actually got his injuries in front-line combat. Throughout, military regulations did not allow him to leave his base to rest at home, except by the leave of his commander.

And in spite of his near-fatal injuries, Sluchynskyi was not initially granted a clean separation — he said they put him down as “partially suitable” for military service. Sluchynskyi said he ultimately had to hire a lawyer and go to court to fight for his discharge. Getting his disability benefits was also a struggle.

Sluchynskyi’s story is so common across the Ukrainian military that when Tetyana Ostashchenko, the head of the military medical service was fired in November, new Defense Minister Rustem Umerov said in a statement that “every service member knows” why she had to go.

The legal volunteer movement Yurydychna Sotnya said that “unfortunately, the number of (legal) requests tied to medical issues is significant.”

The Defense Ministry and the General Staff of the Armed Forces each wrote detailed replies to the Kyiv Independent about these issues. Both avoided directly addressing the prevalence of specific findings.

"Today, the military is a vast living organism of about a million people. With that, there are of course many problematic situations in need of investigation and intervention," the Defense Ministry wrote.

“Since 2022, the Ukrainian healthcare system has faced a situation unprecedented for the modern world. We are constantly working to eliminate existing problems… we are creating a qualitatively new healthcare and rehabilitation system.”

The Defense Ministry and the General Staff listed the reforms that have been planned, launched, or completed, acknowledging the problems indirectly through moves to fix them.

On the technical side, the ministry and the Armed Forces introduced things like electronic queues and simplified document exchanges, and cut down how long it takes for soldiers to get critical files like “circumstances of injury.” Regulation-wise, old standard operating procedures are being changed, international medical standards have been adopted, and a dedicated hotline and website for injured vets have been introduced.

The Defense Ministry changed leadership in November and is reorganizing some departments — in December, Deputy Minister Stanislav Haider told the Kyiv Independent he’d like to see personnel affairs and social security combined into one. The General Staff, which changed leadership in February, wrote that it’s continually working to improve the quality of medical care and administrative services for veterans and trying to make things more “human-centric.”

And Bill 10449 “On Mobilization,” now in parliament, is meant to resolve multiple issues with how VLKs determine fitness to serve.

According to veterans and volunteers, major reforms began to arrive in the second half of 2023. Improvements have been made but there is a long way to go. Many veterans of the full-scale invasion still feel stuck fighting a system that ought to be on their side.

Problems on every level

All troops pass through a VLK on recruitment. Some of the interviewees said that any issues with recordkeeping at this stage can hurt servicemen later.

During active service, sick or injured warriors’ ability to get the care they need depends on their command staff, troops say.

In multiple cities, survivors have had to sit in long, disorganized queues just to get doctors to look at them and sign a piece of paper. This included people who were weak and recovering from physical or mental trauma. This system is improving, especially in Kyiv.

Until recent reforms began to nip this practice in the bud, any interruption in treatment could have made the veteran lose all their combat bonuses from that day onward, as well as other financial compensation, even if the interruption was involuntary (like being transported to another hospital).

While not a military-wide practice, units often require veterans to prove that they took their injuries or lost their gear in combat. When this is done, two witnesses are typically required to avoid being accused of malingering or theft. A few of the interviewees were denied bonuses because the life-threatening wounds they took from enemy fire could not be officially confirmed as front-line injuries. This practice is also undergoing reforms.

Injured service members often have to travel across Ukraine collecting medical documents that determine their future. Some soldiers said their discharge procedures dragged on indefinitely, even as their military status precluded them from getting a civilian job.

Many are not released from service at all, if they have functioning limbs. Occasionally, even amputees or the critically wounded have to fight to get a discharge.

Those who are allowed to walk away frequently have to fight for the money to which they’re legally entitled. From how the interviewees described it, only a fraction will have the stamina to see it through to the end.

Core issue: Military-medical commissions

Many of these problems arise at the so-called military medical commissions. A commission (pronounced in Ukrainian as Viiskovo-Likarska Komisiia or VLK) is like a panel of doctors who decide what to do with service members based on their medical files.

VLKs are second only to unit commanders in how much control they have over the fate of every fighting Ukrainian. Any time a soldier has a wound, injury, or other condition and has to pass through the hospital or several, the resident VLK will be waiting at the end, to decide just how healthy they are and whether they’re fit for duty.

To pass a VLK, a soldier has to get a list of specialists, wait in line for each one, get their tests, and make sure every document is accounted for and hasn’t vanished into the bureaucracy, as they often do.

Reformist NGOs and military staff who know this system blame outdated Soviet orders, the lack of clarity or transparency in the system, the overwhelming scale of the war, and the fact that most records are on paper. They also point out the incompetence, callousness, or corruption among medical commissions or unit command staff.

Efforts at reform have been made and some improvements have already been implemented, both during the tenures of previous Defense Minister Oleksiy Reznikov and his successor, Umerov. However, reforming and auditing the whole system will be a major challenge that will require unbroken political will and dedication to making things right.

“The Soviet system can be blamed on the civilian leadership — politicians, parliament, and military leaders who are against any changes,” said Ivan Minchenko, a veteran. “I understand that it is very hard to reform an army at war. But it is quite possible to improve the medical system or treatment of the injured. It won’t affect combat but it will affect people.”

The corruption factor

Some medical commissions are corrupt. It’s hard to determine exactly how many, but enter “VLK” and “bribe” in Ukrainian into Google and the examples spill out in abundance.

The head of a VLK in Chernivtsi’s regional hospital was arrested for allegedly demanding $500 from a wounded vet to arrange disability benefits. A hospital deputy head in the region was allegedly asking for the same, for similar services. In Kirovohrad Oblast, a surgeon is suspected of charging Hr 40,000 (about $1,000) for a negative combat fitness verdict.

Some doctors’ appetites didn’t appear to stop there. The head of a garrison VLK in Khmelnytskyi was accused of charging $5,000 to mark a service member unfit for duty. One doctor allegedly tried to charge for the same $4,000 in Poltava Oblast; another one was arrested in Kyiv after reportedly trying for $3,000.

Some appeared to be raking it in. One former Chernihiv VLK head who allegedly participated in a draft evasion bribery scheme was found to have $1 million by the Security Service of Ukraine, or SBU. His accomplices reportedly included people who sit on local VLKs and medical offices.

In the interviews, volunteers and service members said that corruption is widespread in VLKs and recruitment offices whose conscripts must go through VLKs before they join their units.

People with disposable income could buy their way out of mobilization, while recruiters swept poorer areas for conscripts, according to interviewees. Alleged VLK forgeries were detected on people trying to flee Ukraine under false pretenses. It became such a big problem that President Volodymyr Zelensky fired all recruitment office heads in August.

One conscript, a Kyiv resident identified in the story as Anatolii, was sent recruitment papers in his home village. His daughter, who worked closely on his case with a lawyer, said it was common practice for recruiters to come with buses to villages in the area and collect as many men as they could. Rural residents tend to be poorer, with less access to civic infrastructure.

The Defense Ministry said it takes corruption seriously and asked for any known cases to be reported to both it and the police. The General Staff said the same thing — that it encourages reporting corruption to both the police and the military.

Luch: Put through the wringer

After a series of hospital stays in Bakhmut, Dnipro, and Vinnytsia, Sluchynskyi was up but plagued by problems with his vision, memory, and knee. He came to Kyiv in May 2023, to sort out his documents and try to get discharged. "That was when the bullshit started," he said.

Just getting to the doctors was a pain. The time window to get specialist referrals and to then see those specialists was one and the same — between 8 and 10 a.m. Some of the tests were being done in a different hospital.

“There were times that I’d speak to the doctor for 10 minutes and I stood in line for eight hours. It’s not organized. It strongly affects morale,” Sluchynskyi said. “Many can’t bear it and go home. Previously, if you missed one day of care, you didn't get combat bonuses.”

One surgeon measured the hole in Sluchynskyi's skull and wrote its dimensions as 1 square centimeter. The actual size was 26 square centimeters. Sluchynskyi found another doctor and had him watch the surgeon take another measurement, writing it correctly this time.

All this effort went to waste because the checkups expired while he was waiting for the military to establish that he was wounded in combat. He had to start over.

This meant he couldn’t go home. "Until you have the VLK results, you have to be constantly stationed at the base,” Sluchynskyi said. “And theoretically, you might have to fight.”

When the findings came back, he said that they were riddled with wrong dates and other errors. When it was redone, the commission ruled to summarily discharge him. A little prematurely, it turns out, because Sluchynskyi was then denied access to a scheduled appointment in a military hospital.

“As long as you are intact, the country needs you,” Sluchynskyi said. “When you’re not whole, you’re not really needed.”

To qualify for disability benefits, he had to go through a different panel called a medical social expertise, abbreviated as MSEK in Ukraine.

There are three tiers of disability in Ukraine, from requiring round-the-clock care at category one, to having full function and minimal entitlements at category three. Sluchynskyi applied for category two, for people who can take care of themselves but cannot hold down a job.

He said his doctors recommended he be granted category two, yet the medical expert panel went with category three. He surreptitiously recorded a doctor from the panel telling him that they would not grant him anything but the lowest tier — the Kyiv Independent listened to this recording. Sluchynskyi said he then appealed and finally got category two but per the rules, he must return each year to repeat the procedure.

How this comes about

Lyubov Halan, spokeswoman of Pryncyp, the top veteran care reform organization in the country, said these problems come from outdated Soviet military rules, a callous culture among doctors and commanders, reliance on hardcopy, disorganization, and corruption.

But if she were to rank one reason above all others, she would single out the military’s flowchart for medical decisions. Written in peacetime, it could not cope with the scale of Russia’s invasion.

Until recently, the military medical commission system was based on Order 402, an outdated standard operating procedure. Order 402 has a rudimentary model for how to treat casualties and decide if they’re fit to serve.

But this order was vague. “Partially fit,” service members cannot be in the special forces, but they can be in light territorial defense units meant to defend the rear. However, with Russia's invasion, territorial defense sees about the same amount of action as the special forces do.

When reviewing a person’s medical file, medical commissions don’t consider comorbidity or the sum impact of all conditions. They only look at the main diagnosis. In this situation, many physically unwell people may be forced to continue serving.

According to the General Staff, Ukraine has now adopted the international ICD-10 diagnostic system. Before the adoption, Ukraine used an older model, leading to communication issues with allies. Commanders who don’t know medicine or don’t trust VLKs often ignore them.

Worse, many service members are required to have a document “Form 5” or “circumstances of primary trauma” that establishes a causal relationship between defense of the homeland and the injury. This affects a service member’s future status and available benefits.

Investigating every time someone is wounded takes forever and runs into a problem if all eyewitnesses are dead and the paper combat log is gone.

Halan said her organization successfully fought to reduce how long it takes to get a Form 5 and eliminate the mandatory investigation requirement. However, some units still investigate.

In August, the old system for determining fitness for duty was changed with the adoption of Order 490. Halan said there were clear improvements in the procedure. Unfortunately, the changes also increased the number of conditions that under certain diagnoses can be ruled as fit to serve. Pryncyp said these conditions don’t lead to fitness.

Djinn: Thanklessly discarded

The circles of Dante’s hell are a popular metaphor for the system’s many torments. National Guard infantry squad commander Viktor Shepelia, callsign Djinn, said he’s been through all of them.

This volunteer fighter was heavily wounded twice in the span of two months in 2022. The first time, a mortar shell collapsed his earthen dugout on top of him and set him on fire. When they pulled him out, he had a skull fracture, shrapnel wounds, ruptured eardrums, and an intense concussion.

The second time, an anti-tank shell flew over him and blew behind his back, flinging him forward. Four fragments shot into his knee. They were so close to an important nerve bundle that Ukrainian surgeons were afraid to operate and risk permanent damage. Casevac couldn’t get to him right away, so he had to do his best to command his men, as the officer in charge.

The injuries gave him epilepsy, but when he showed up for treatment, he was confined to a hospital ward filled not just with other epileptics but all kinds of emotionally disturbed soldiers, with a strict ban on letting people go home for the weekend or step out to eat — soldiers could only be picked up by members of their unit. He felt worse after these treatments. “A soldier comes to recuperate — they shove them in the nuthouse,” he said.

Ivan Minchenko, another veteran, shared a similar description of hospitals. He said the strictness made him feel like a prisoner.

All told, the injuries created a litany of acute and chronic health problems for Djinn. "My diagnosis is a long read — that's what this (combat) cost me," he said.

That’s why he was stunned when the VLK investigation concluded that of the above injuries, only his knee and hearing damage are verifiably connected to combat with the enemy. This directly affects how much money the military has to pay him.

He, too, had to produce witnesses to testify that his shrapnel injuries to the back and being buried alive happened in the line of duty, which is a lot to ask on Ukraine’s battlefields.

“If there is only one witness available for trial or both witnesses have already been killed… you’re f*cked,” Djinn said. “If I don't have these witnesses or if they're dead, nobody saw it. If I'm the only one left alive, how am I going to prove anything?”

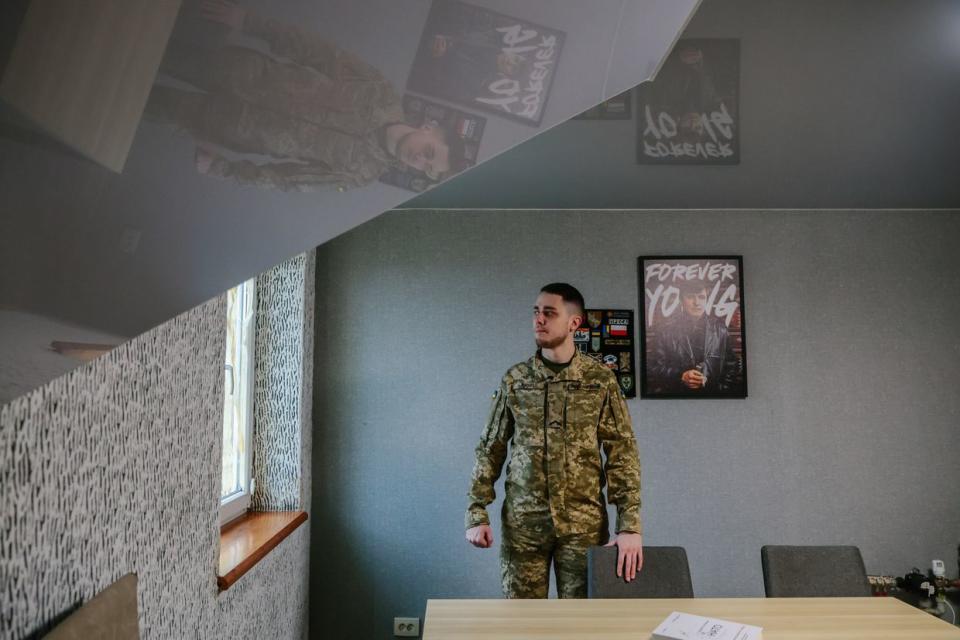

Djinn photographed in his apartment in Kyiv, Ukraine on Jan. 29, 2024. (Olena Zashko / The Kyiv Independent)

Many say they stop receiving their combat bonuses and injury compensations during treatment. At the time of the interview, Djinn said the state owed him Hr 600,000 or $15,500. As of publication, he has received Hr 150,000 ($3,900).

"I didn’t go to war for the money," he said. “But if you owe me money, you better give it to me.”

Serhii: Fighting for release

Serhii Shuliepov used to command a squad in the National Guard. He fought in the Kyiv suburbs: Bucha, Irpin, and Hostomel, and in eastern Ukraine. His recollections include guarding bridges for friendlies around Sievierodonetsk and Lysychansk, being the last to leave. At Rubizhne, his squad had to break out of an encirclement to escape the enemy.

Eventually, he was concussed in combat. During treatment, medics found that Shuliepov had untreated gout in his body and it weakened a big part of his skull. He had to get surgery reinforcing the weakened areas with a metal plate.

Doctors said that any sufficient pressure vibrations on this metal plate, like from incoming or outgoing fire, would reliably kill him. The VLK surgeon suggested discharging Shuliepov. However, the chief medic wrote in the conclusion that Shuliepov is partially fit for the service. Being partially fit is no guarantee that he wouldn’t be ordered into combat.

“One has no way out,” Shuliepov said during his interview.

Shuliepov challenged the decision with a lawyer, submitting a request to undergo a VLK at the Central Medical Commission of the Interior Ministry. After one month of waiting, the Central VLK sent him back to undergo an initial phase of the medical commission.

Eventually, the VLK granted Shuliepov’s discharge documents. It took him from March to the end of October 2023 to finalize the discharge decision.

Yurii: Betrayed by his commanders

Yurii Shapoval moves about on crutches as he tells his tale. When the war started, the 49-year-old single dad had a good job, taking care of his three-year-old daughter. But he wanted to fight for the motherland. He left his daughter with his mother and joined the military. He was hoping Russia would be sent packing in six months.

He said his unit, 53rd Brigade’s 1st Battalion, was in a ramshackle state. “I left military service soon after the Soviet Union collapsed,” he said. “I thought I knew what a mess was. That was a holiday by comparison.”

Deployed to the hot battlegrounds around Volnovakha and Volodymyrivka in Donetsk Oblast as a combat medic, Shapoval’s squad was among the last to retreat from an overrun position. The man behind him was hit and as Shapoval stopped to help him, he was also hit. The bullet destroyed his ankle joint. He eventually crawled away and was picked up by friends.

It took 12 surgeries to start repairing the damage. His leg still hurts so much, he needs painkillers just to get through the day. When he tried to get help for his dependency in a Dnipro military hospital, he said they called him an addict and threw him out. He said that hospitals in Irpin and Vinnytsia treated him much better.

Now he has to prove he was wounded in the line of duty or he said the 53rd won’t give him the document that certifies that he was wounded in combat. But during the retreat, the paper combat log was lost. He’s been calling them since spring 2023.

“They tell me: ‘Present two witnesses.’ I say: “Are you morons? What two witnesses? I’m the only one left. Out of the last 10 guys, I’m the only survivor.’ But they demand two witnesses… I was told that I was labeled ‘absent without leave’.”

Anatolii: Disabled man ordered to fight

A Kyiv woman, named Anna for this story, granted multiple lengthy interviews to the Kyiv Independent over the past five months while helping her 53-year-old father Anatolii with his case. By request, both real names have been altered to avoid military and legal backlash.

Anatolii was judged unfit for the front line when he was mobilized at the start of spring 2023. But in April, he was sent to Vinnytsia for infantry training. Less than a month later, he sent a message that he was being sent to reinforce the 110th Motorized Brigade near Avdiivka.

Anna found out later that while in Avdiivka, he was woken up in the middle of the night and sent to the zero line, where he spent three days in a trench. When he got back from the trench, his section leader chewed him out for “disappearing.”

Anatolii called the recruitment office, trying to get a copy of his medical documents to prove he’s unfit for the front line. He said they showed him a brief snapshot, which said that the 53-year-old had no health problems.

Wearing armor tore his meniscus and his health declined. While in his deployment area, he often had to sleep outside in a sleeping bag, which aggravated his thrombosis. The military doctors couldn’t offer more than topical cream and painkillers at first. When Anna found him a civilian doctor, they refused to see him, saying they’d be in trouble with the military.

After eventually going through two hospitals, he was resting in Kyiv. Before he could recover fully, his section leader ordered him back to Donbas to wait in reserve, west of Avdiivka. The 110th was recently pushed out of the town after defending it for close to two years. Anatolii wasn’t part of this retreat — he and some comrades were waiting for their orders at the time.

Flawed system with unscrupulous administrators

Mykhailo, who lost his legs in Donbas fighting the Russian-controlled proxies several years before the full-scale invasion, said the flawed system has been in place for a long time.

He said wounded people had to wait in line for an indeterminate number of days. That included people with holes in their skulls or concussions that made them unable to stand or sit up for extended periods. Sometimes, only to be told, “You have arms and legs, why are you here?”

“The doctors treat the casualties with contempt. There’s a feeling like you came to ask (the doctors) to borrow money… even though I’m just asking for them to follow procedure,” he said. “It makes you want to open the conversation by rolling a grenade (into their office).”

Soldiers rarely get told that they need to collect all their documents from their unit and the hospital where they were treated. That includes the primary injury report, an unbroken chronology for the health condition, and how it’s tied to the motherland’s defense.

Djinn said veterans have to be careful to track what they need. If some pencil pusher takes your document, “you’ll never see it again — if you didn’t photograph it, it doesn’t exist. It takes as little as one missing document for the whole thing not to exist.”

Mykhailo said that even though the law is very clear, VLKs often “scrupulously forget” it and only remember “when you come to them with an envelope” with a bribe inside.

“A soldier comes to them and says ‘I heard I’m entitled to this.’ And they tell him ‘What you heard isn’t a thing.’ Except it is a thing, but the soldier believes them because they’re officials. But if he goes to a lawyer, the lawyer confirms that they are eligible.”

Soldiers can fight this in court but few of them bother, said Mykhailo, whose pension should be higher than what he gets now. As someone who is creating a health center for disabled veterans and interacts with many of them, he thinks that few have the drive to go all the way.

“Out of 100 eligible pensioners, only 10 will make it to the fund, out of those 10, just four will make it to court,” he estimated. “And that's in Kyiv. Imagine someone who lives in a village, with a once-per-week marshrutka to a nearby city.”

Ivan: Standing up to the system

Ivan Minchenko is one of the stubborn soldiers who fought for everything the country owes him. He joined up on the day of the invasion, serving in the 110th Territorial Defense. In April 2022 he was wounded near Novodarivka in Zaporizhzhia Oblast “in connection with defense of the motherland,” as the VLK established.

He managed to escape half-encirclement near the Donetsk regional border, with the 114th battalion. He then participated in an assault on Pryiutne. His unit was trapped and couldn't retreat, taking over 20 casualties. Minchenko had bullet and concussion wounds, which disrupted his neurological function, affecting his use of one arm.

He went to his disability panel in 2023, which gave him disability 2 and confirmed he had major health problems. And yet, he said the VLK found him partially fit for duty.

“When I went into the VLK and said I have disability 2 officially confirmed, and have medical documents backing it up, they said that's logical, we'll talk to the leadership. I spoke with the VLK head and she said directly — we're putting you as partially fit because we put you down as partially fit before.”

There are no ways to leave, meaning disabled service members are often forced to keep serving. Meanwhile, service members whose family members are disabled can leave with no issue. “This is f*cked up,” Minchenko said. “Why isn't anyone taking political responsibility?”

He said there's an unwritten rule in the military that your treatment can take up to a month, which was inadequate for many, including himself.

Though he was wounded in April 2022, he didn’t get a certificate of his circumstances of injury until November. This process has officially been sped up to a maximum of five days, but that wasn’t the case when he was serving.

Denied their legally entitled benefits

Minchenko’s story is common. Service members wounded in combat are entitled to their combat bonus for the entire treatment period. Many don’t get theirs, but are too afraid to go to court for it. Soldiers who fight for theirs like Shepelia and Minchenko are in the minority.

“Service members simply don’t know their own rights,” Minchenko said. “I solve these kinds of issues very simply. I submit it for consideration by the Cabinet of Ministers, the Veterans Ministry, and the Defense Ministry.”

Ivan Minchenko in Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine on Feb. 11, 2024. (Kate Klochko / The Kyiv Independent)

In reply, the ministry said that Minchenko must receive his full combat bonuses, which he eventually secured. “After that, in our separate battalion, everyone else also started getting money,” he said.

“In the previous battalion, they had told me that they never paid anyone like this. I said ‘Guys, there is no question here… I will take you to court, and you’ll be forced to pay.”

Minchenko also had to fight for his disability. He said he mailed a request to Veterans Affairs and they made sure he got the right status. He expects to have problems claiming his pension and plans to fight for it in the European Court of Human Rights.

Reforms from late 2023

In August 2023, changes were made to the main by-law on military medical examination, and standards for VLKs themselves.

Legal aid volunteer group Yurydychna Sotnya praised the automation of some procedures, the expansion of electronic document management, and the introduction of electronic queues. Throughput in many places is still low but the Kyiv Independent got to see these improvements firsthand in Kyiv accompanying a veteran named Oleh, who had a fairly smooth ride through his physicals.

Changes were made to how fitness to serve is determined and the list of documents proving a causal relationship between injury and defense of the motherland has been broadened. VLKs must consider medical results conducted by non-state doctors.

Deadlines for processing complaints have been clarified. Special mandatory medical examinations have been established for service members who were Russia’s POWs, and who have been treated abroad.

The reform also clarified the exchange of service members’ documents between healthcare institutions and military units, territorial recruitment, and social support centers.

However, confusion still remains about the practical status of people deemed “partially fit” for duty, according to Yurydycha Sotnya.

Many other things have not changed either: a rather opaque procedure for passing the VLK, corruption risks, the difficulty of appealing decisions, and more.

“As for the procedure for passing the military medical examination itself: the procedure has not changed in principle,” Yurydychna Sotnya wrote.

Read also: After 10 years of war, Krasnohorivka in new danger as Russia advances in the east

We’ve been working hard to bring you independent, locally-sourced news from Ukraine. Consider supporting the Kyiv Independent.