Aaron Burr was on a mission to commit treason. And Cincinnati was a pit stop along the way

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

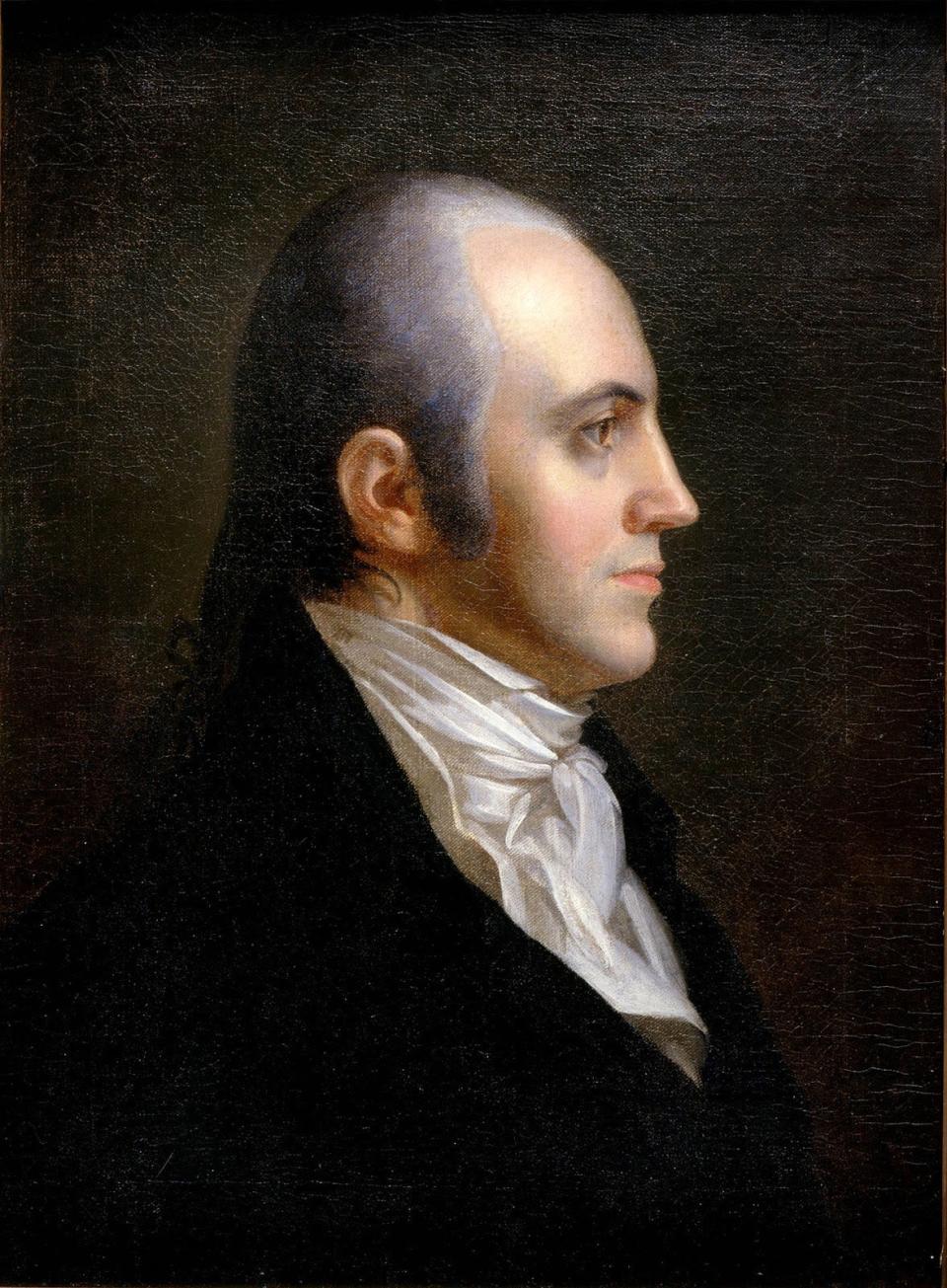

Not long ago, people knew Aaron Burr only from a funny “Got Milk?” commercial. After Lin-Manuel Miranda’s 2015 musical phenomenon “Hamilton,” everyone knows of the famous duel on July 11, 1804, between Alexander Hamilton, the brilliant Founding Father and first secretary of the treasury, and Burr, “the damn fool that shot him.”

The fact Burr was the vice president of the United States at the time makes it even more intriguing.

But Burr’s misadventures didn’t end with the duel.

He spent the next three years traveling up and down the Ohio River Valley and to New Orleans, plotting and scheming, gathering supplies and supporters with designs for some sort of expansion in the West.

What exactly that plan was, no one really knows for sure. But what became known as “the Burr conspiracy” resulted in him facing charges of treason.

Our History: Before making eclipse history, this astronomer documented Cincinnati in the 1700s

Burr ‘a dangerous man ... not to be trusted’

Even before the fateful day at Weehawken, New Jersey, when Burr shot Hamilton, the vice president was already planning his next steps.

Burr was brilliant and ambitious but not well liked. George Washington hated him. Hamilton called Burr “a dangerous man, and one not to be trusted with the reins of government.”

Burr alienated his own party, the Democratic-Republicans, during the 1800 presidential election when he and Thomas Jefferson received the same number of votes. It was understood that Jefferson was to be president with Burr as vice president, but Burr didn’t accede, forcing a vote in the House of Representatives to decide the election.

And the Federalists hated him for killing Hamilton.

So as his term as vice president came to an end in 1805, Burr turned his attention to the West, including the Louisiana territory the U.S. had just purchased from France.

Was Burr planning treason against the U.S.?

Burr could have been building up an army to illegally invade New Spain territory, specifically Texas. Or to revolutionize the West and join with Louisiana to form a new republic. Or to merge the Western states and Louisiana with New Spain as a new empire, with Burr as emperor.

“If we had all the burned and scattered letters and records back from the ashes of time, if we knew beyond doubt that everyone told the truth, we would still have a story shot through with conflicts and question marks,” historian Buckner F. Melton Jr. wrote in his book, “Aaron Burr: Conspiracy to Treason.”

“No one will ever know what Burr was really up to.”

We do know two of his main co-conspirators: Gen. James Wilkinson, who was then the Commanding General of the U.S. Army and secretly on the payroll as a spy for Spain.

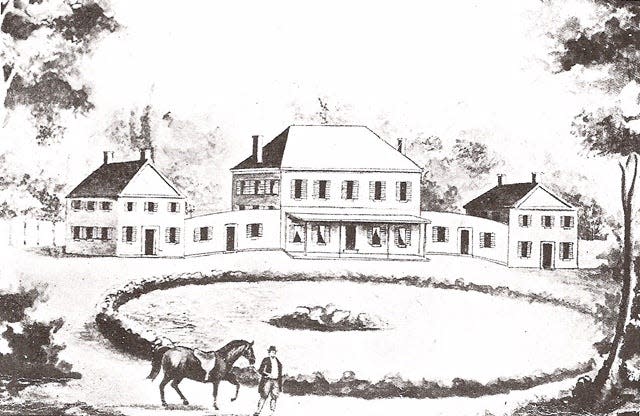

And Harman Blennerhassett, an Irish immigrant who owned an island on the Ohio River near Marietta, Ohio. Burr used the mansion on Blennerhassett Island as a headquarters, where they stockpiled supplies and soldiers. (Today, the island is a West Virginia state park.)

Burr’s visits to Cincinnati

Burr made trips to the western country in spring 1805 and fall 1806. When passing through Cincinnati, he stayed at the home of Sen. John Smith in Terrace Park.

Elder Smith, as he was known, served as the minister of a Baptist church in the settlement of Columbia (now the Columbia Tusculum neighborhood of Cincinnati). He was also a politician in the Northwest Territory, advocating for Ohio’s statehood. In 1803, the Democratic-Republican was elected as one of the state’s first two U.S. senators.

Smith’s home at 1005 Elm St. still stands, though it’s much different than the original four-room log structure. “The exterior has been radically altered,” the Terrace Park Building Survey reports, “but the interior with its low ceilings, wide planked floor boards and hand blown glass panes, still retains some of its original integrity.”

Not everyone was welcoming to Burr.

Judge Jacob Burnet, a prominent Cincinnati jurist, refused to meet Burr when he came to town because he “considered Col. Burr a murderer,” according to “History of Cincinnati and Hamilton County, Ohio.”

With concerning rumors swirling about Burr’s plans, Sen. Smith wrote to his friend in October 1806:

“We have in this quarter various reports prejudicial to your character. It is believed by many that your design is to dismember the Union; although I do not believe you have any such design, yet I must confess from the mystery and rapidity of your movements that I have fears.”

Burr responded:

“If there exists any design to separate the Western from the Eastern States, I am totally ignorant of it. I never harbored nor expressed any such intention to any one, nor did any person ever intimate such design to me.”

His denials were, basically: I don’t know what you’re talking about, and I have never written or published anything saying otherwise.

He had been careful – except he trusted the wrong man. He sent Wilkinson a letter in cipher code that said he was ready to act. Burr finally committed himself in writing with details of the plan. Wilkinson turned around and spilled the beans to the government, omitting his own role in the conspiracy.

Kentucky’s U.S. Attorney Joseph Hamilton Daveiss brought Burr before a grand jury in Frankfort three times in late 1806 to face charges that he had planned a military expedition to invade Spanish territory, which was in violation of the federal Neutrality Act. Burr, defended by the young attorney Henry Clay, was acquitted each time.

Jefferson finally did something about that pesky Burr. In November 1806, he issued a proclamation against the western insurgents, calling on state militias to help control the West.

On Dec. 10, 1806, the Ohio militia intercepted the boats filled with weapons, supplies and soldiers at Blennerhassett Island, but Harman Blennerhassett escaped. The militia ransacked the island the next day. Burr was hundreds of miles away at the time, which was a key point.

Blennerhassett and fewer than 100 men met up with Burr and they headed down the Ohio River toward New Orleans to enact their plot, not knowing Wilkinson double-crossed them. Upon hearing of the bounty out on them, Burr and his men surrendered to authorities at Bayou Pierre in Louisiana.

How the Constitution defines treason

Burr went on trial in 1807 at the federal court in Richmond, Virginia, presided over by Chief Justice John Marshall. The president himself accused Burr of treason.

The Constitution defines treason against the U.S. as “levying war against them.” Conviction requires “the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act.” The act that was the basis for the charges against Burr occurred on Blennerhassett Island on Dec. 10, but Burr was not actually there, so there were no witnesses to his involvement.

The trial ended up narrowly defining what treason is according to the Constitution, and despite Jefferson’s fervent wishes, Burr’s case did not meet the standard. The verdict: “We of the jury say that Aaron Burr is not proved to be guilty under this indictment by any evidence submitted to us. We therefore find him not guilty.”

Although there was no evidence Smith was involved in the conspiracy, he was painted with a wide brush for his association with Burr. A Senate committee chaired by John Quincy Adams recommended Smith be expelled from Congress. The expulsion fell one vote short of the two-thirds required, but Smith resigned anyway in 1808.

So was Burr a traitor? In this case, historians don’t really know because of the lack of evidence. Burr was certainly up to something aimed to give him power, whether of his own settlement or his own empire.

Melton offers this perspective:

“Aaron Burr was a traitor. His offense took place in his 19th year, in the summer of 1775, when he took up arms against his sovereign, George III.”

In that, he was in good company, including every one of the Founding Fathers. So treason wasn’t a foreign idea.

Melton adds, “A successful treason is not treason at all, but a revolution.”

Burr didn’t come close to succeeding.

Additional sources: “The Aaron Burr Conspiracy in the Ohio Valley” by Leslie Henshaw, National Constitution Center, National Endowment for the Humanities, “Cincinnati Curiosities” by Greg Hand, American Experience, Wikipedia.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Aaron Burr's mission to commit treason had a brief stop in Cincinnati