After 96 Years, Archaeologists Finally Found the Missing Part of a Legendary Statue

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 1930, German archeologists uncovered the lower half of a massive statue, estimating that it likely originally stood some 23 feet tall.

Now, U.S. and Egyptian archeologists have announced the discovery of the long-missing top half in thankfully pristine condition.

A proposal has already been submitted to unite the bottom with the long-missing top half, and the discoverers are confident of its approval.

Some 96 years ago, German archeologist Günther Roeder unearthed the lower half of what would’ve been a massive, 23-foot-tall statue of Ramesses II—one of the most celebrated pharaohs throughout all 31 dynasties of Ancient Egyptian history. Roeder found the statue 150 miles south of Cairo in the Minya Governorate, near the modern-day city of El Ashmunein. In ancient times, this area along the Nile was known as Khemnu. It served as a provincial capital in the Old Kingdom of Egypt (2649–2130 BCE), and was later called Hermopolis Magna when Romans ruled the Mediterranean.

Many treasures of the region’s illustrious past were known to be buried in the surrounding desert, and while Roeder’s discovery proved remarkable, the rest of the enormous statue he found remained lost to time…until now.

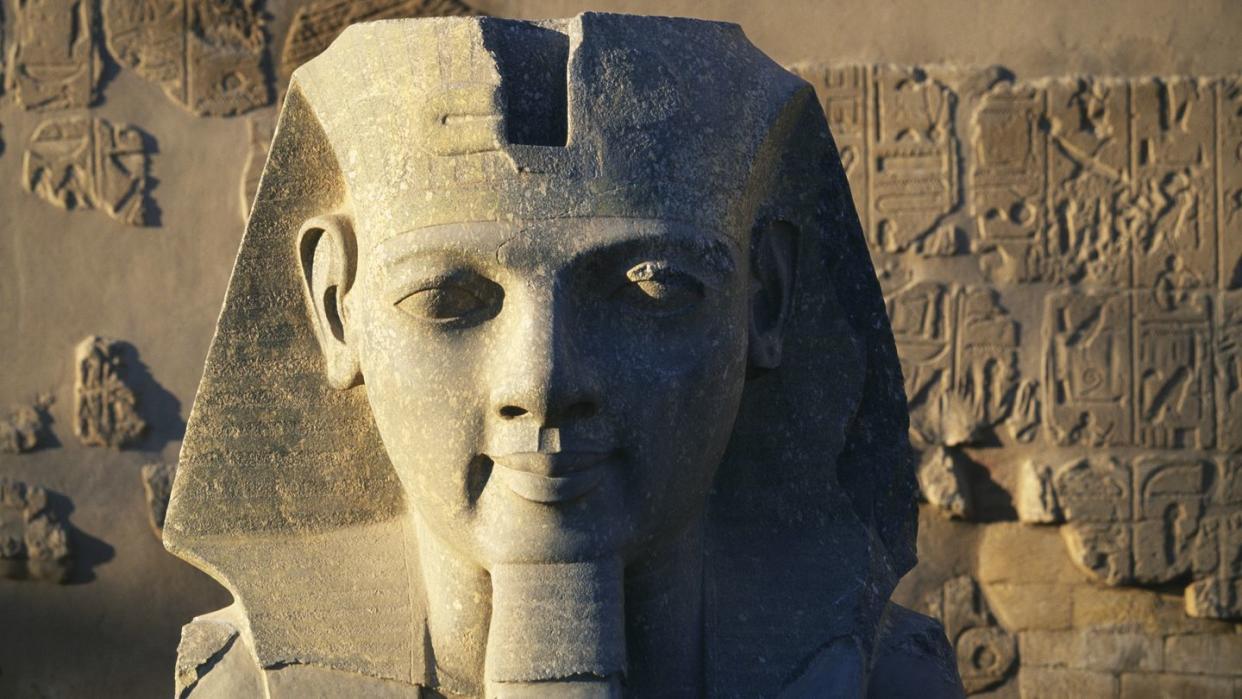

Back in March, the Egyptian archeologists—in partnership with U.S. experts—announced that after 96 years, they’d finally found the missing upper half of Roeder’s statute. Speaking with Reuters, the experts from the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities reported that the upper half stretched some 12.5 feet tall, and depicted Ramesses II wearing a headdress topped with a royal cobra.

However, the discovery of this ancient statue—and exquisite preservation—was far from certain when the statue was first discovered lying face down in January.

“One problem with Hermopolis is that it’s close to the Nile. After [the building of] the Aswan Low Dam, the water table became a huge issue. There was no guarantee that the stone would be OK,” Yvona Trnka-Amrhein, assistant professor of classics at the University of Colorado Boulder and co-leader of the team said in a press statement. “Sometimes sandstone is uncovered that is basically just sand or degraded limestone. It could have just been a lump of rock.”

Luckily, after further excavation, the team confirmed that the statue was remarkably well-preserved and contained another amazing find—traces of blue-and-yellow pigment could be found on the statue’s surface. Hopefully, further analysis of this pigment will help researchers understand the context of the statue’s creation, as well as its original appearance.

“We knew it might be there, but we were not specifically looking for it,” Trnka-Amrhein said in a press statement. “It was plausible that the rest of the statue might be there, but it was a total surprise.”

Thankfully, the hunch proved correct, and Egyptian co-leader Basem Gehad has already submitted a proposal to reunite the two pieces together at long last (Roeder’s lower half still remains on site in El Ashmunein). Trnka-Amrhein expects it to be approved.

You Might Also Like