7 ways Donald Trump is just like the Founding Fathers

Photo illustration: Yahoo News. Photos: Corbis (2), AP, Getty Images (2).

About half a dozen times in the past few weeks I have been taken aside by a 20-something who’s looking for reassurance that the republic will not end. There has never been any campaign like this in the history of the nation, they say, and they know this is true because they’ve read it everywhere.

“We have officially hit a new low in political discourse,” declared Stephen Colbert (after Trump’s penis allusion on national television). Next, the Huffington Post warned, “Recent violence at Trump rallies marks a new low for American politics.” Not long after that, the Financial Times said: “Trump v Cruz hits new low as wives dragged into fray.”

A new low. A new low? Heavens no, I say, in my best wizened voice. Not even close. Rather than ending the republic, these folks would fit right in with the men who founded it. What’s distressing is not that this adolescent baiting and sniping is unheard of, but that it isn’t. We should have outgrown this by now.

To wit:

Name calling: Donald Trump, in particular, is so fond of calling people names that a running list of epithets being kept by the New York Times now includes more than 200 of his targets. Not a one of his zingers comes close to what leaders and would-be leaders spat at each other throughout history though, and not just because Trump uses far fewer syllables.

Jefferson’s supporters, for instance, described Adams as suffering from a “hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.” Adams’ supporters in turn called Jefferson “a mean-spirited, low-lived fellow, the son of a half-breed Indian squaw, sired by a Virginia mulatto father.” Theodore Roosevelt called Woodrow Wilson “that Byzantine logothete, supported by all the flubdubs, mollycoddles, and flapdoodle pacifists.” (Translation: A logothete is a paper pusher; a flubdub is one who speaks nonsense; to mollycoddle means to treat with kid gloves.)

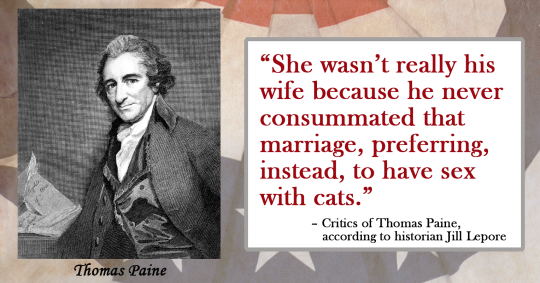

And then there was Thomas Paine, who wrote “The Rights of Man,” and whose critics, according to Harvard historian Jill Lepore, described him as follows:

Horribly ugly, smelly, rude and relentlessly cruel…caus(ing) his first wife’s death by beating her while she was pregnant and abus(ing) his second wife almost as badly, except that she wasn’t really his wife because he never consummated that marriage, preferring, instead, to have sex with cats.

In other words, no one has (yet) accused anyone of bestiality this campaign season, so we’re still ahead.

Speaking of sex, and the sexes: Our earliest leaders may have descended from Puritans, but there was nothing puritanical about them. A certain current hit musical incorporates Alexander Hamilton’s affair as a plot device, as it led to the young country’s first sex scandal. What the Broadway version doesn’t include is John Adams’ opinion that Hamilton’s actions were caused by “a superabundance of secretions, which he couldn’t find enough whores to absorb.”

Jefferson, in turn, was accused of having sex with his slaves, an accusation that would not be proven for centuries, but that didn’t stop his contemporaries from making it. Benjamin Franklin, who wrote a sex advice column in the 1700s (which included ruminations on why younger men should have affairs with older women because “regarding only what is below the Girdle, it is impossible of two women to know an old from a young one”), was described by Adams thusly: “His whole life has been one continued insult to good manners and to decency.”

“It got scatological and salacious,” says Joseph J. Ellis, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “Founding Brothers.” “History is full of bad behavior.”

John Quincy Adams was called a pimp, which he probably wasn’t. Andrew Jackson was called a bigamist, which he wasn’t, but his wife was, because she married him without realizing that her divorce was not yet final. Not enough to smear Jackson’s wife, opponents went to work on his parents: “General Jackson’s mother was a common prostitute, brought to this country by the British soldiers! She afterward married a mulatto man, with whom she had several children, of which number General Jackson is one!” wrote one newspaper at the time.

So, no, Senator Cruz, wives and families have not historically been off-limits. Julia Grant was called cross-eyed. Mary Todd Lincoln spent too much money on dresses and put too much faith in séances. Nellie Taft smoked, and Rachel Jackson was plump. When Warren G. Harding died in office, political gossipers said his wife, Florence, poisoned him. No, there are no instances of nude photos of would-be first ladies used in attack ads, but that’s likely only because no other would-be first lady has posed in the nude professionally.

They called each other cowards: Cruz did so directly. (“Donald, you’re a sniveling coward, leave Heidi the hell alone.”) Trump did so indirectly, saying he is the only one strong enough to stand up to Putin, Mexico, ISIS and hecklers at campaign rallies. Back in the day, politicians used the term when they were talking about things like actual war.

When former Mexican War Gen. Winfield Scott tried to unseat President Franklin Pierce, also a Mexican War general, Scott’s supporters dubbed Pierce “the fainting general.” Pierce had, in fact, once fainted on the battlefield and had to be carried off. What his opponents didn’t mention was that it wasn’t fear that made him faint. It was the pain from a wrenched knee caused by a lurching horse.

There were also a lot of snipes about the sturdiness of the other guy’s spine. Ulysses S. Grant, the 18th president, remarked that James Garfield, the 20th president, “is not possessed of the backbone of an angleworm.”

Theodore Roosevelt, then assistant secretary of the Navy, said about William McKinley, who was serving his first presidential term: “McKinley has no more backbone than a chocolate éclair.” (And, yes, I also wondered, with all the talk lately about hand size and such, whether this éclair was really just an éclair. Roosevelt biographer Edmund Morris assures me that “TR was, alas, incapable of double-entendres.” I still choose to believe Trump is not actually the first of our presidents to allude to declare his is firmer, if not bigger.)

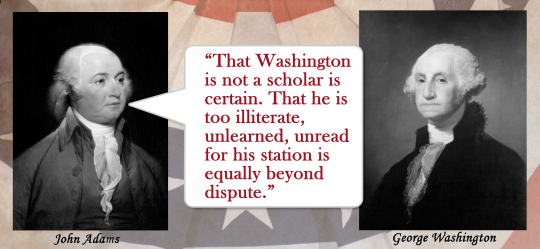

When not questioning their opponents’ “spines,” our forebears questioned each other’s brains: “That Washington is not a scholar is certain,” John Adams said. “That he is too illiterate, unlearned, unread for his station is equally beyond dispute.” Jefferson agreed and advised ambassador to France James Monroe to tell the French to essentially ignore Washington because he was senile.

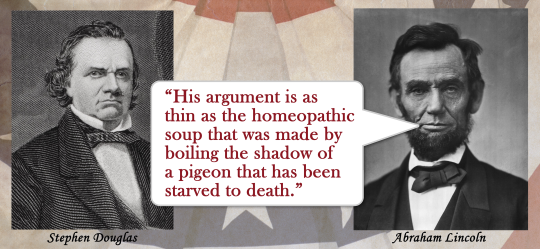

Lincoln — the now revered and idolized Lincoln that Republican candidates are falling over themselves to admire — also wasn’t considered terribly bright. “Buffoon,” “Ignoramus Abe” and “well-meaning baboon” (a phrase with clear racial overtones) were some of the names Lincoln’s critics summoned during his 1860 campaign against Stephen Douglas. And Lincoln, in turn, said of Douglas, “His argument is as thin as the homeopathic soup that was made by boiling the shadow of a pigeon that has been starved to death.” (The idea that Lincoln was uneducated, bordering on illiterate, followed him into the White House. After a certain speech in Gettysburg, Pa., the Chicago Times wrote, “We did not conceive it possible that even Mr. Lincoln would produce a paper so slipshod, so loose-joined, so puerile, not alone in literary construction, but in its ideas, its sentiments, its grasp. He has outdone himself.” So there’s that.)

They have basically called their opponents insane: “Pathological,” Trump said of Ben Carson, before the former surgeon dropped out and endorsed the businessman.

It was hardly the first time the sanity of a powerful politician has been questioned. There was, as already noted, Jefferson calling Washington senile and concerns that Lincoln suffered from what had not yet been named “depression” and agreement among critics that “Bloody” Andrew Jackson was probably simply crazy. Then, in 1964, a survey of members of the American Psychiatric Association found that more than half of respondents believed that Republican candidate Barry Goldwater was clinically insane. (Their suggested diagnoses included “megalomaniac, paranoid, and grossly psychotic … schizophrenia.”)

This led to the establishment of the “Goldwater Rule,” in which the APA’s ethics requirements ban psychiatrists from commenting about any individual who they have not actually treated. There are exceptions if you add caveats and disclaimers, though, and this election cycle includes a Vanity Fair article in which psychologists and social workers opine that the Republican frontrunner is “actually a narcissist.”

They flirted — and more — with violence: Trump has boasted that he could stand “in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose voters.” Andrew Jackson kind of did. Estimates of his duel participation tally vary from a dozen to several hundred, but there was at least one in which the other guy died. That would be Charles Dickinson, a rival breeder of racehorses, who accused Jackson of reneging on a bet, and also brought up the bigamy thing. Voters seemed to agree that Jackson had been insulted and was simply defending his honor.

Trump has also warned there may be riots if he is denied the Republican nomination, and that too has happened. In 1912, supporters of Theodore Roosevelt and those of Howard Taft brought bats, guns and even dynamite onto the convention floor. And the possibility that a spurned candidate could “take his voters and go home” in a third-party run has also happened, that same year in fact, when Roosevelt left the convention, booked a ballroom across town and declared himself the nominee of what came to be known as the Bull Moose Party.

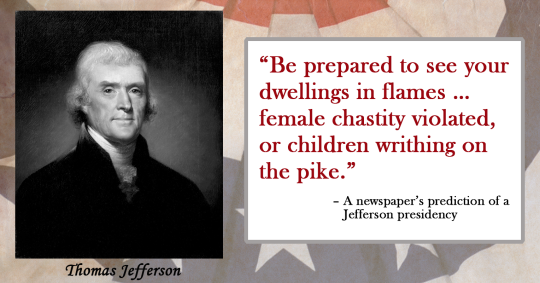

They predicted the end of the republic: All this bad behavior was justified by the fear that the target of that behavior was a threat to the future of the country. Whether that was truly felt or simply manufactured is between each politician and his conscience, but the case was continually made that the other guy would destroy America.

Usually that didn’t happen. During the election of 1800, for instance, one editorial warned that should Jefferson win, voters should be “prepared to see your dwellings in flames … female chastity violated, or children writhing on the pike.”

Sometimes, though, the alarmists were right. Rabble-rousing crowds did swarm unfettered, after Jackson’s election — trampling the public quarters of the White House on Inauguration Day, breaking furniture and china while trying to get to the free refreshments. (Eventually the bowls of punch were moved onto the lawn and the mobs followed.)

And then there were those who said the election of Abraham Lincoln would literally lead to the disintegration of the United States. It did. At least for a while.

I explain all this to the 20-somethings, and they have more questions — mostly about whether they should fear civil war.

Again, I try to put things in historical context. Most of the time, I remind them, the worst actors never actually won the presidency. William Randolph Hearst (a newspaper magnate, with more money than couth, who spent the modern equivalent of $54 million of his own money on a presidential campaign in 1904) never got the nomination. Theodore Roosevelt’s third-party bid was unsuccessful. Goldwater was soundly defeated. The American electorate has regularly shown itself able to pull up before impact.

Oh, they say, then historians aren’t worried? So I don’t have to be?

Not exactly. As Doris Kearns Goodwin put it recently on “Meet the Press”: “As a historian, I might say, ‘200 years from now, a historian will be able to detail this the way I couldn’t.’ But as a citizen, it’s pretty scary and sad.”

Yes, this may have happened in the past, she and others say, but that doesn’t make it OK when it happens now. Norms and standards have changed over the centuries, and our leaders are expected to change too. More is at stake in the modern world, where nations are dependent on the U.S. economically and militarily. And unlike even a few election cycles ago, every imprudent utterance goes out to that world unfiltered.

“For many decades most of what was ‘published’ — broadcast on television or radio, printed in books, newspapers and magazines — was edited, reviewed by a person or more often a group of people, an editorial staff, whose entire purpose was to exert judiciousness,” Lepore says. Most recently, though, “nearly all of what is ‘published’ — posted, tweeted, blogged, televised, dash-camed — is unedited. There is media, but it no longer mediates.”

What then to tell the 20-somethings?

“I don’t know what you tell to young people,” admits Ellis, who teaches many of them at Mount Holyoke. “You can tell them the republic is not going to go out of existence, I am pretty sure of that. The good thing about history is we’ve seen worse and survived it. But what things will look like after this mess” of a campaign? “I have no idea.”

What he said.

_______

Yahoo News graphics photo credits: Background images: AP, Getty. Portraits: Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images, Corbis (2), GraphicaArtis/Getty Images, Corbis, Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty images, Corbis, Universal History Archive/Getty Images, Stock Montage/Getty Images, Corbis.